Shop is endlessly fascinating for me.

It comes out of roughly the same period as Hirsh Lekert, after Leivick’s trip to the Soviet Union in 1925, and was published in the same journal, Der Hammer. But while Hirsh Lekert was a hagiographic drama of the individual and the role of the individual in this brave new world the revolutionaries were hoping to form, Shop is more of an ensemble piece. Every character has their own role to play — much like the gears of the machines they are surrounded by on all sides.

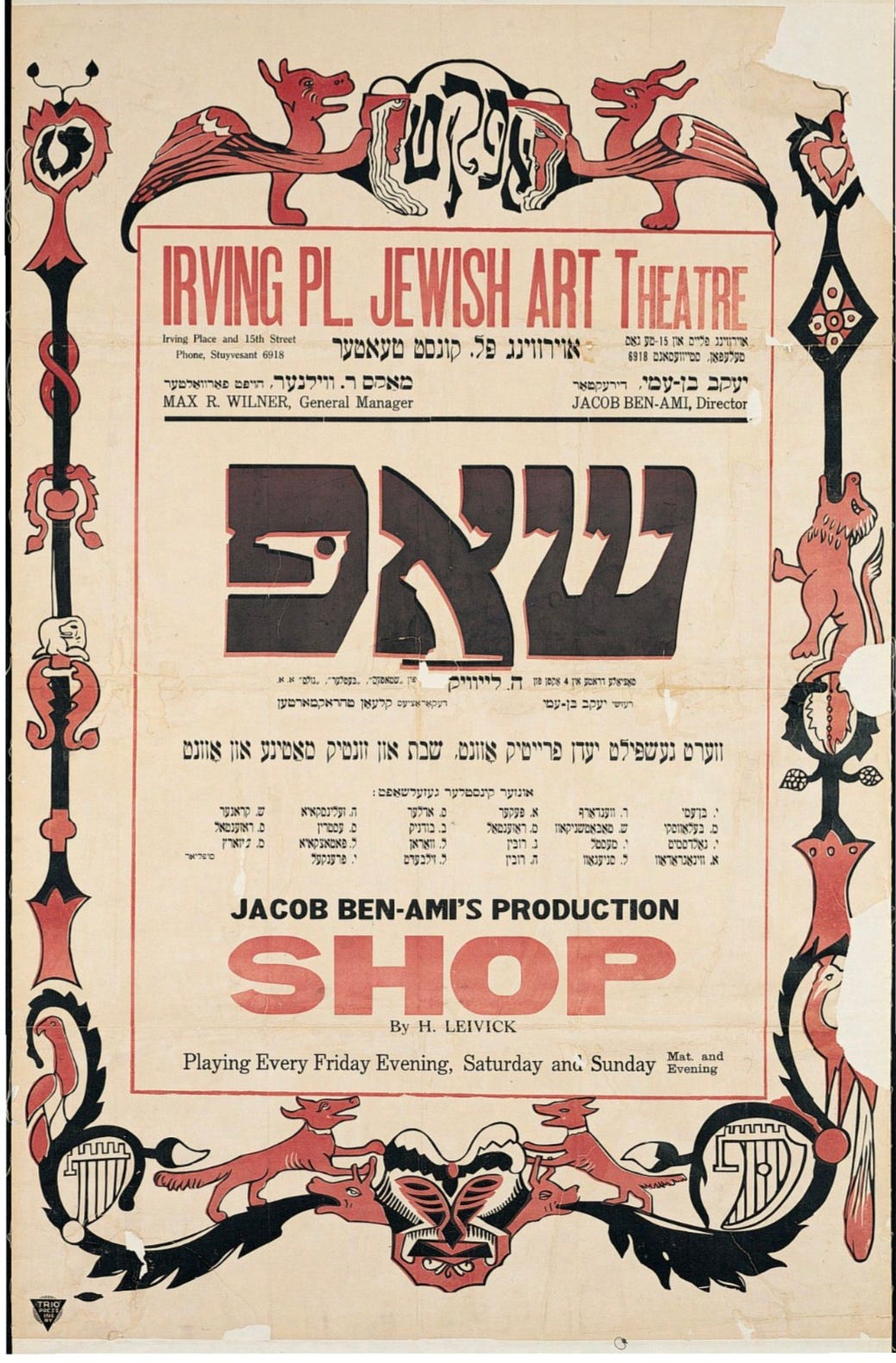

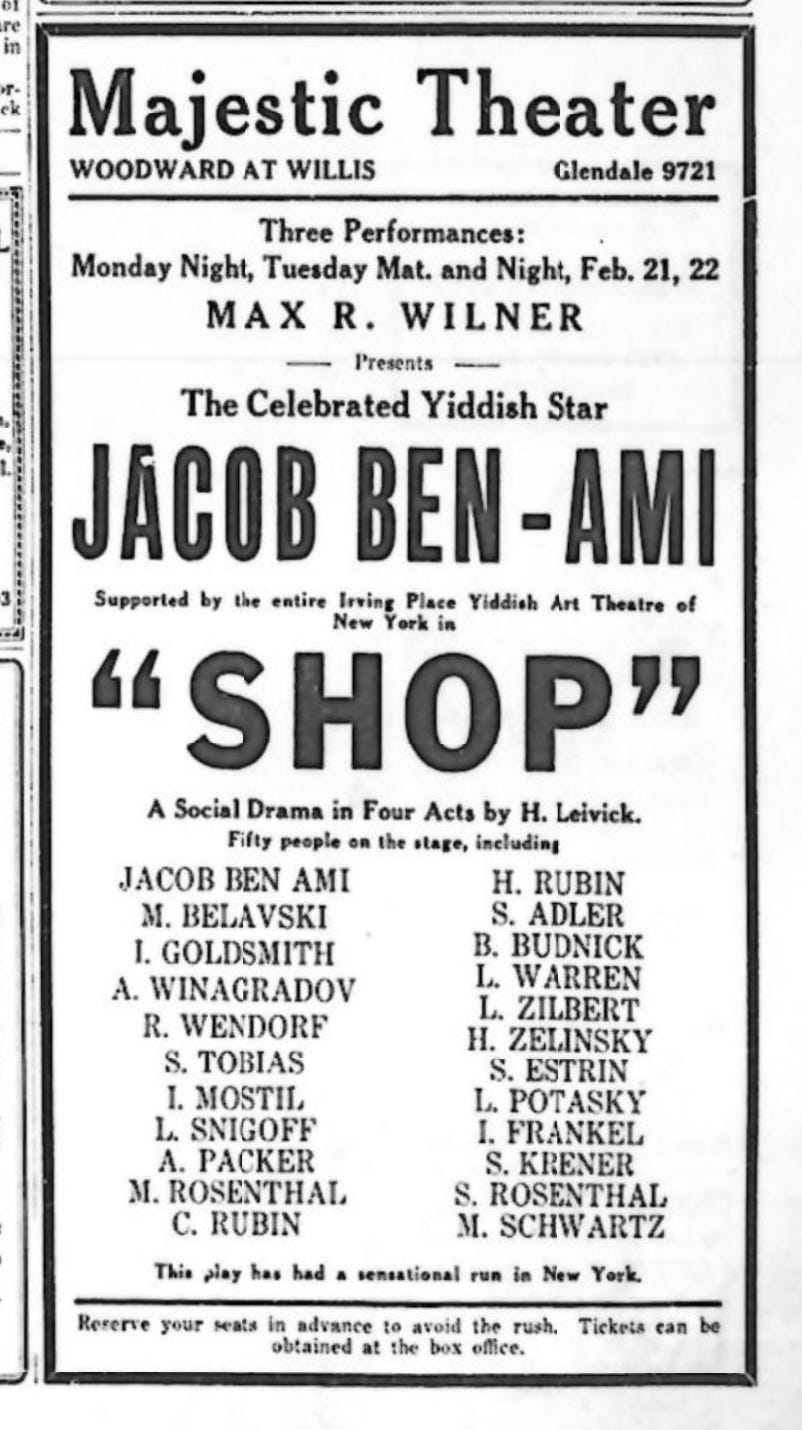

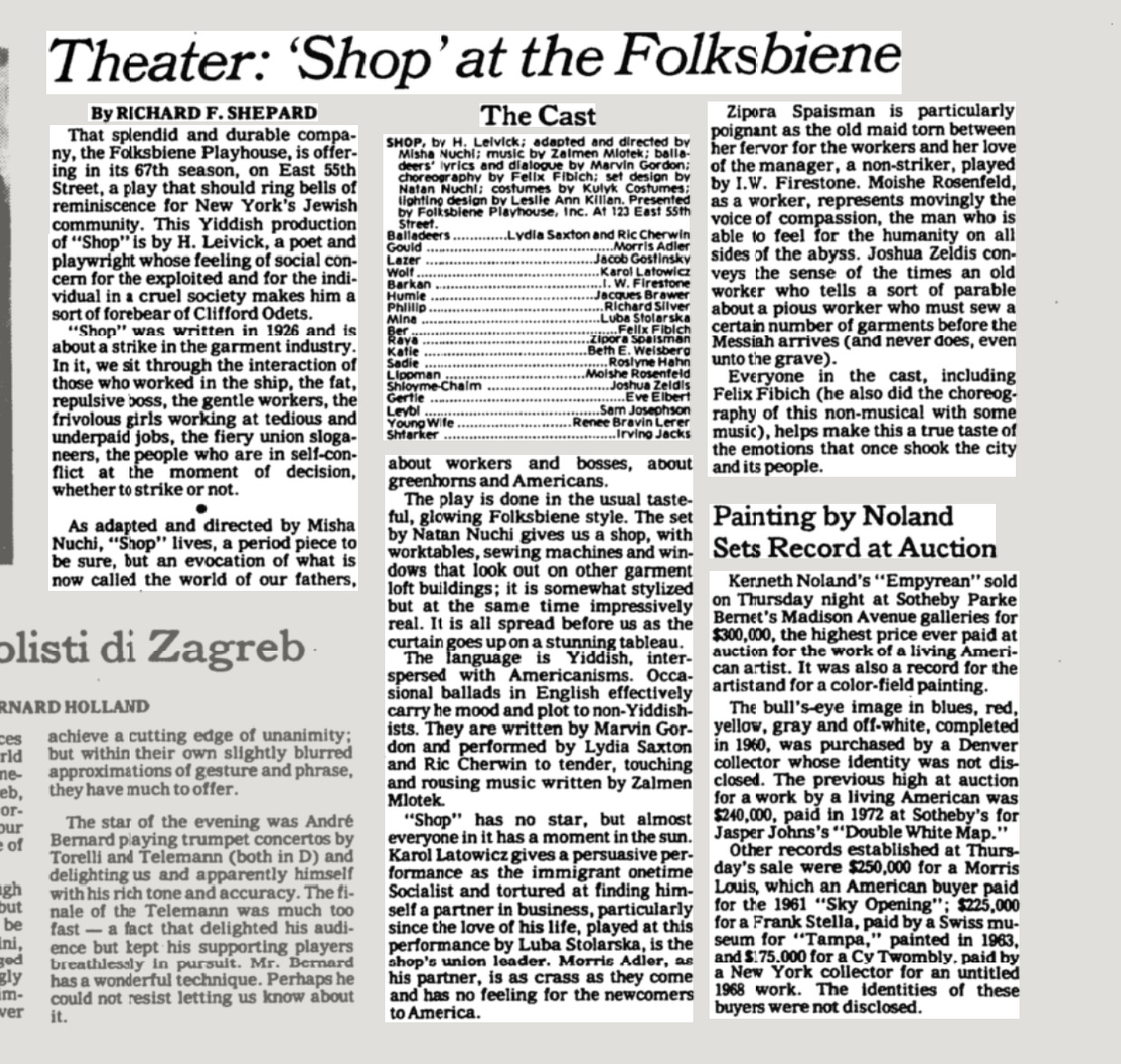

Shop, like Rags and Golem, is one of Leivick’s better-known plays, and one of those which has been performed relatively recently (ok, within my lifetime, but I’ll call that recent). Like Rags, it has a foot in reality and the dramatist’s autobiography—it is based on Leivick’s own experiences training as a cutter of children’s clothing in a sweatshop in Philadelphia.

It’s a play which, at junctures, also reminds me of other American plays of the same period, such as Treadwell’s Machinal — particularly Shop’s Raye, who is destined to be ground in the ‘machinery’ of the shop much the way that Treadwell’s Young Woman is also ultimately doomed by the mechanical life around her and can only break free of it with her death.

Shop as Identity Play

Rather than a scene by scene breakdown — I’m going to give Shop a look through three different lenses. Starting with Shop as a play about identity. Particularly Jewish, immigrant identity. In this respect, it might not seem so different than many of of Leivick’s other plays, both realist and fantastic. We’ve seen his characters struggle to say who and what they are before. We seen them struggle to be who and what they are. And we’ll continue to see that.

Shop gives us a cast of characters that (largely) know who and what they are and are willing to make a stand for it. Not knowing who you are and where you stand is a dangerous proposition in a Leivick play.

This and all following excerpts from H. Leivick, Shop, 1926. Translations and errors therein my own.

Leibl knows precisely who he is. What he is. Not Louie, but Leibl. Always fear the man who wants to completely sever from his past in Leivick. Here, that’s Wolf and Mina — the revolutionaries who have broken from the last, tearing out, respectively, conscience and heart. This man who knows who he and who refuses to answer the boss when he call him by any name other than his own marries the ‘Queen of the Strike,’ Gertie — who also knows what she is, beneath her glib exterior, and turns her back on the advances of Philip the scab.

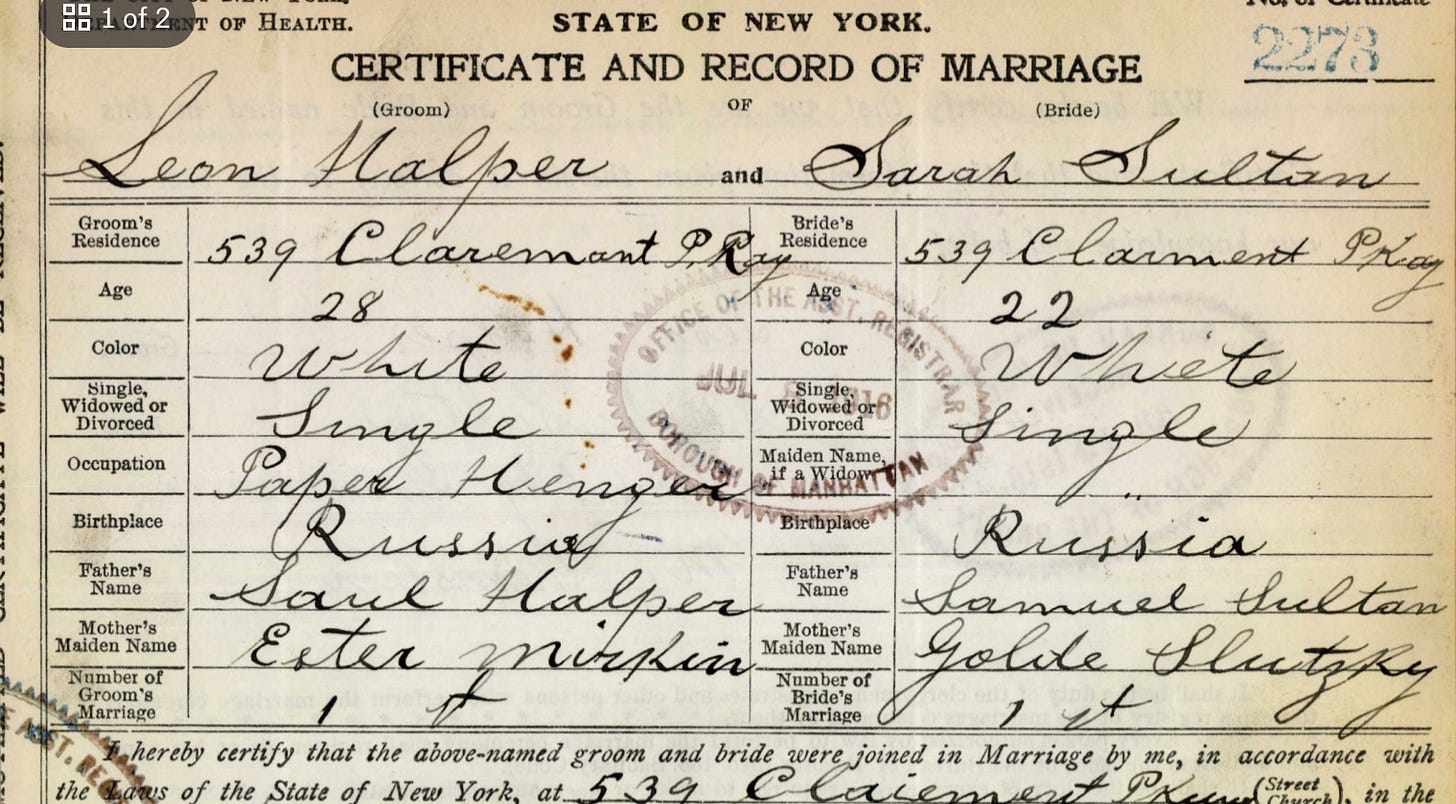

Leibl’s struggle to assert himself seems, at least to me, extra poignant in light of the fact this shop is based on the one Leivick worked in while in Philadelphia, he’s also learning to be a cutter — and Leivick himself got married as a ‘Leon.’

A brief attempt at being ‘Leon ‘ was made, it seems.

Like the poet ‘Lev,’ who sits obediently at the feet of an elder Yiddish poet in The Poet Went Blind, Leibl seems to have more than a bit of the dramaturge himself about him.

Ber was a coachman — he is very firm about this former identity, and is equally firm about what is treated jokingly as a sort of moral ascent in this world. He’s now a presser and a firm union man. Lipman, too has changed his identity from nearly-a-rabbi to union man.

Both are more humanitarian shifts than Mina’s from bleeding heart revolutionary and Wolf’s former lover to cold-blooded union organiser.

The anti-union characters are equally steadfast in their self-knowledge: Philip knows and understands he is entirely driven by money (as are Sadie and Katie, whose wages provide them with a bit of freedom to act as their like). Hymie identifies himself as a family man, that need is what rules his actions. Barkan, too, is in it work the money and to become a boss himself someday.

All of them know where they fit into the whole. Even the tragic Raye knows that she cannot, not in every aspect, outrun who and what she is and her place in the world: An ‘old maid,’ used by Barkan, replaceable in almost everything that she does.

The only one who doesn’t know? Wolf. He’s changed his name, changed his profession from revolutionary to boss, but what does it mean? Not even he is very sure until the end, when it becomes clear that he will not, cannot, be a heartless boss. Nor can he ever be Mina’s lover again. But can he find who he really is now? The play leaves that question unanswered.

The Shop as an Autonomous Entity

Is the shop, itself, alive? Wolf, one of the bosses, begins the play wanting to know what the shop, as a sort of independent organism, is doing. Does it hate him, lack respect for him, what does it say and think?

Gould, the other boss, doesn’t believe in the autonomy of the shop. It doesn’t think anything, he tells Wolf. It’s a building full of machines and hands. Both are entirely replaceable. Jewish, Black, Chinese, he doesn’t care. Raye, one of the operators, tells us that if she leaves the shop, another ‘old maid’ will sit at her machine.

The machines, the shop itself, doesn’t care so long as there is someone there to ‘operate.’

The shop is power, according to Mina, the de-factor leader of the union emerging in the shop. And when it wins, the shop sings and dances. The individual people do not matter, so long as the shop prevails. She stands for the brutal Left, all politics and no people. She tells us how she has torn love from her heart. The workers are grist for the machines who give the creature it’s pulse and social ideas. For all her brutality, though, Wolf’s idealism has run around and sunk in her absence.

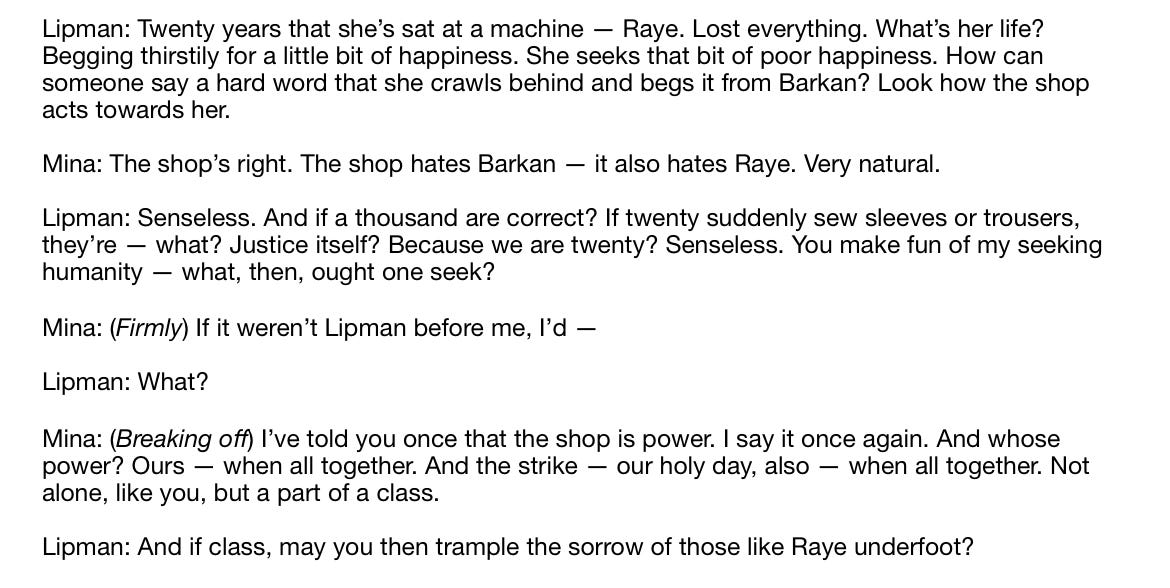

Lipman’s (Mina’s opposite number amongst the workers) shop, on the other hand, is one of accident, senseless and unconscious — where a man who was nearly a rabbi in the old country might find himself thrown by fate to cut, press or sew. His is a shop of individuals which make up the whole. He wants to see the beating hearts inside it, acknowledge the tears. It is Lipman who saves the innocent Raye (even if only temporarily) from the strikers’s kangaroo court.

Charney, incidentally, draws attention to these doubles — and opposites — in Shop: Mina and Gould (the same, but left and right, respectively) and Lipman and Wolf (both suitors for Mina, worker and boss, respectively) and this fits into the scheme of Leivick’s many, many doubles and alter egos.

Leivick touches the idea of a many-headed, many-legged single beast in Oyf Tsarisher Katorga, and this is a play intimately linked with Russia, coming on the heels of Leivick’s return from a visit to the Soviet Union and was first published in the pages of Der Hammer, the Communist monthly associated with Morgn Frayhayt, as well.

Charney identifies the many-headed creature of ‘shopkeeper’ in Leivick’s ‘Different’.

There aren’t really any bosses left on the stage at the end — Gould reappears but says nothing, at the mercy of the workers, and Wolf has quit. The shop-creature, far from being unconscious for all but Lipman and Gould, is very much aware. The machines, both at the beginning and end of the play, run with no operators as all. The shop itself is bride, machines adorned in flowers just as the actual operator-bride, Gertie. It knows who scabbed, Hymie says. It also demands retribution. It might even demand blood.

Raye declares herself the shop — almost ugly, scorned. Unforgiving. She throws herself from the roof and we know that what she predicted may well come true, her machine will be filled and things will continue.

It’s all the same to the shop and there is only the shop.

The only hope of change is the new alliance between Mina and Lipman; the strategising brain and the compassionate heart of the shop.

And this is a clear message in that period immediately following Leivick’s return from the Soviet Union, published in the Communist Der Hammer: progress cannot be made at any cost, at the expense of the individual. The characters (and by extension, the audience) is constantly being asked what/who they or others are. Or declaring who and what they are now — why they — we — should care and why they should be cared about.

Shop — the Musical

Leivick remarks at least twice in writing that he is a ‘limited’ singer — but also that he does, in fact sing and has done to in the past. His piece for the Edelstadt Book contains an essay-length exploration of the importance of song to him during his years in prison. Previously, we saw the integration of song into Hirsh Lekert — the traditional nigun finding its counterpoint in the revolutionary song and the eventual song of the hero himself.

In Shop, we find these revolutionary songs colliding with a different sort of music — that of the ‘New Home’ and the modern. The boss used to be a Bundist, now he’s a capitalist pig. We used to sing Liessin’s song about a hero dying in the snow in a yurt in Siberia (‘The Lena’), now we dance on the sweatshop roof, amongst the skyscrapers, to jazz (and a round of ‘Yes Sir, That’s My Baby’).

Gertie starts the play singing parodic little snatches of tunes, related to whatever situation is at hand — stopping when the crossroads of the strike is reached.

The play is also a dance, the shop itself a kind of dance-floor — changing partners, in and out. Shop, just before the half-way mark, is definitely taking on the aspect of a sort of dance: Opening with Leyzer’s dance with his broom moving on to the couples doing a different sort of ‘dance,’ changing partners, to the strains of revolutionary songs as well as jazz on the roof

All this from a man who also claims not to dance. Dance actually figures pretty significantly for him — who is and isn’t doing it and what for. See the chain dance in Keytn and it’s real-life counterpart in Oyf Tsarisher Katorge. Also the dances on his trip to Israel, were he cannot join in the hora and in With the Surviving Remnant, where Leivick decides that he must, in fact, finally join in the dance.

It’s important who doesn’t join the dance on the rooftop at the end of the second act — as well as who doesn’t come up for it and who joins in unwillingly. And then what interrupts it — news of the strike.

The ‘music’ briefly starts up again during the strike, where it is used to attempt to pacify the jumpier scabs who want only to sing and dance, who want the extra wages and candy promised by Gould, the more mercenary of the two bosses.

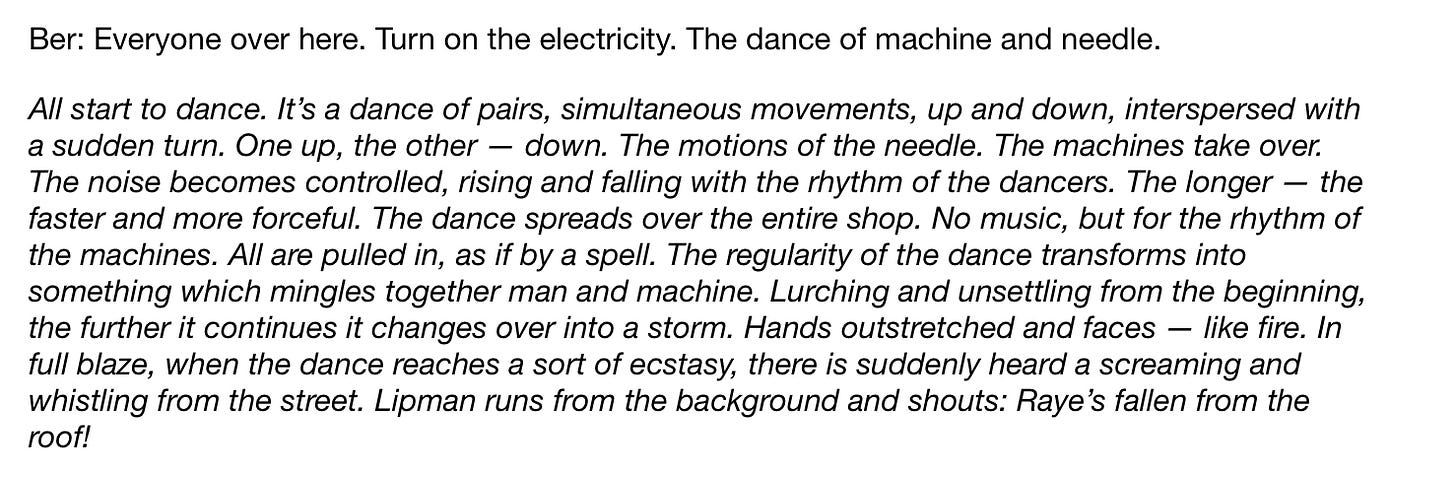

But a different sort of music emerges for the wedding at the end — the operators the musicians, the machines the instruments. Raye commands that they dance the dance of the machine and needle. Is this dance truly any different beneath the skin than the dance of the chains in 1929’s Chains? All the participants are in some way captive and beholden to the larger structures around them, using the dance either to demonstrate submissiveness to these structures— or to show defiance against them. Leivick often has these moments where strange rituals seem to be (re)enacted — the sacrificial burning of the shop in Different, the darkly orgiastic ‘wedding’ in New Poems’ ‘Lider fun Umkum’ and that half submissive, half-defiant dance of Keytn. Here’s another.

Once again, the dance is interrupted.

Not Leivick’s only stage wedding, of course, And not the only one interrupted by death/the dead.

The wedding itself is by turns charming and sinister — the first operator’s badchan-like song hinting at violence done to the body by the tools of the shop. The red blanketing everything and bedecking the bride both a reference to their strike-time engagement and invoking blood (we might remember that Edelstadt’s and Ansky’s revolutionary flags, whose songs are sung in snatches here and throughout Leivick’s works, are always red with blood). Leyzer the elderly ex-revolutionary threatens his own death amongst the machines and Shlomo-Chaim, purveyor of the mystical chassidish-style tale, tells the tale of an operator forced to sew beyond his own death.

Raye’s suggestion of the dance of machine and needle is likewise laden with doom — it isn’t subtle either, as the couples pair off and imitate the movements of the machines. We know from the first act, from the first lines, that running the machines empty, without operators, carries the danger, the near inevitability of breaking the needle. The shop, emptied of humanity, will break its own components with its uncontrolled action. A shop, a world and a song devoid of love and respect breaks Raye.

The musicality was recognised and underscored by the Folksbiene production of late 1981, where new songs (in English) were included.