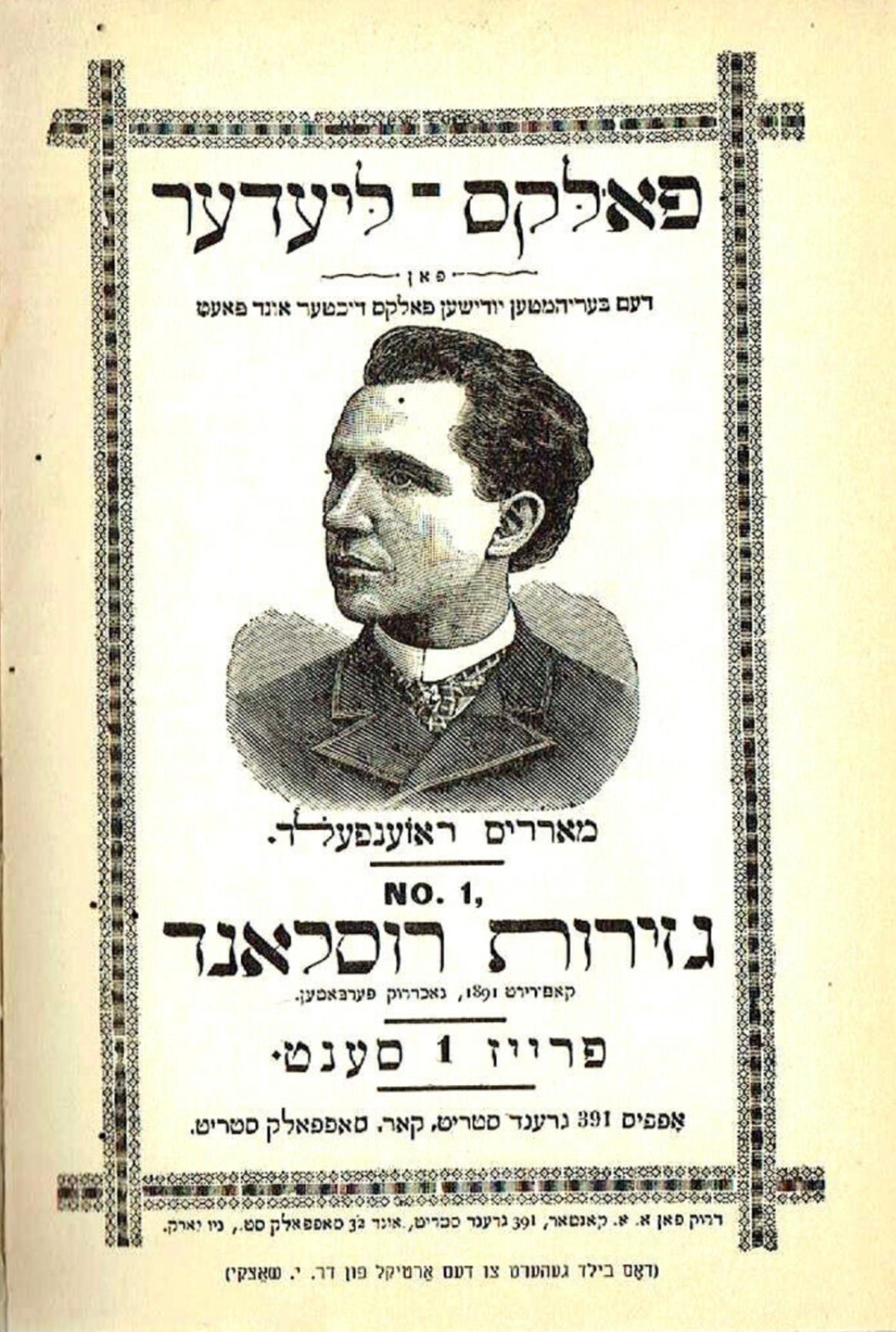

An ad for a collection of poems by Morris Rosenfeld, reprinted in the first issue of Leivick and Opatashu’s Zamlbikher, 1936.

In 1936, Leivick leaves the JCRS Sanatorium in Denver…

and heads back to New York.1 There, he and Joseph Opatoshu set up their own anthology series, Zamlbikher. It would eventually run to eight volumes, the last of which in 1952 was dedicated to the ‘liquidated, silenced or killed Jewish writers in Soviet Russia.’ A large assortment of the great and the good (if largely male) appeared in its pages, including Isaac Bashevis Singer, Kadia Molodowsky, Leyzer Volf, Chaim Grade, Aaron Zeitlin, Melekh Ravitch, Rokhl Korn, Mani Leib, Jacob Glatstein, Y.Y. Trunk, Avrom Sutzkever ….and the two editors themselves.

Issue 3, published in 1938 included Leivick’s play ‘The Poet Went Blind.’2

There’s no great mystery in the play as to who it’s meant to be about — Leivick tells us straight away, in a brief introduction, that his inspiration is fellow poet, Morris Rosenfeld:

From H. Leivick, ‘The Poet Went Blind,’ Zamlbikher, 1938.

Even without this note from Leivick, the disguise of ‘Maxim Thornfeld’ poet and employee in a ‘shop,’ financially struggling, his first book of poetry all but unfindable3 (and his wife, ‘Rose’) is a paper-thin one.

Rosenfeld had previously appeared in Leivick’s 1927 poem (collected in 1932’s New Poems) ‘Letter to America from a Distant Friend.’ And the Rosenfeld we find there is an intensely embittered one, who rails against the state of Yiddish and poetry, and of whom the younger poet is seemingly afraid:

From H. Leivick, ‘Letter to a Distant Friend,’ New Poems, 1932.

Written following Leivick’s trip to the Soviet Union in 1925, the poem isn’t necessarily a rosy look at America.4 The Ten Brothers kill and eat the Golden Peacock, we get a taste of American (and Leivick’s own) concept of race, the drudgery of working in a ‘shop,’ and what it’s like trying to be a practicing artist in America as an immigrant — the time and space for art being basements, after long working days.

And in The Poet Went Blind, we get a real sense of how Morris Rosenfeld, er, Maxim Thornfeld, might conclude that ‘Yiddish is tfu.’

For starters, his son, Bob, is full of English. Even his dialogue in the first act in full of phonetic English. And he can’t see why it is his father wouldn’t choose to write in English, for an English newspaper, and actually earn his living by his art. What Bob doesn’t — and can’t — see is that the language is the art. Inextricably. What Bob does see, though, is his father’s books being kept in the toilets of his friend’s houses, as though Yiddish is something secret, shameful, almost scatalogical.

His brother, Boris, cannot see this indivisibility of language and literature either. He’s a ‘moderniser’ of a different sort: why not, he asks Maxim, write in Hebrew? The landlord is at the door, demanding back rent, Thornfeld is suffering from heart trouble and, worse still, his own Yiddish paper is turning him out, not only refusing to raise his pay, but returning his poems.5 He is being replaced by another, a newer immigrant. A more sophisticated and famous model from Europe.

Hebrew poets, Boris is convinced, don’t starve the way the Yiddish ones do. They wouldn’t be abandoned at a time of such need. He brings journals of Hebrew writing into Thornfeld’s house. Thornfeld’s reaction is to let his own, Yiddish, books fall to the floor.

Into this mix, the uproar of Hebrew books, possible eviction, Bob deciding is he going to run from both his father and Yiddish, the reappearance of Thornfeld’s old mistress, Helen, there arrives Lev. I don’t think we can truly read Lev any other way than as Leivick’s own avatar in the play. A younger, newer poet, one with a respect for physical labour, who writes on social themes, was exiled to Siberia…

From H. Leivick, ‘The Poet Went Blind’.

Above we find Thornfeld/Rosenfeld again saying that Yiddish is ‘tfu’ — to be spat upon6 — though we know, of course, that neither Thornfeld/Rosenfeld nor Lev/Leivick truly believe that.

And then the poet, as it says on the tin, goes blind. Or does he?

The media vultures descend, eager to make a meal out of misfortune. Now Thornfeld’s not only a struggling Yiddish poet, but one with an increasingly tragic story: he has lost his sight, suffers increasingly from heart trouble, his son has run away from home and his wife is now also ill.

From H. Leivick, ‘The Poet Went Blind.’

Leivick goes after his news-man colleagues with a rather sharp pen,7 broadly caricaturing the reporters, the photographers and the editors who come to Thornfeld’s door, attempting to force their way in around Boris.

From H. Leivick, ‘The Poet Went Blind.’ Words left in italics are in phonetic English in the original text.

As a poet, Thornfeld may have been abandoned. As a news story, though, he suddenly belongs to the world — and the English-speaking world, too, without even writing in the language. Because misery not only sells, it easily translates. And Thornfeld is quite aware that his value to them lies not in his poetry, but his story.8

From H. Leivick, ‘The Poet Went Blind.’

At this juncture, a certain amount of uncertainly is injected into the proceedings. Leivick says in his introduction to the piece that Morris Rosenfeld pretended he was blind. And on the heels of Thornfeld’s skepticism of suddenly being celebrated by the media, being offered a charity fund by a man who against the continuation of Yiddish literature, and not only regaining his old post, but being offered his choice of posts at Yiddish papers, he loses his temper with the gathered crowd. Perhaps he speaks metaphorically, but in combination with Leivick’s introduction, it throws his supposedly disability into uncertainty:

From H. Leivick, ‘The Poet Went Blind.’

Is he in fact blind? Or is it a charade to see how he will be treated? Certainly the doctor’s reaction to him hints something is slightly amiss, though it is never explained what.

Whatever the fact of his blindness or not, Thornfeld sees what the idea of it has granted him: a sort of living martyrdom. Though he (and we, the readers) knows the more sordid side of things — his rages, bitterness, possible malingering, his infidelity.

From H. Leivick, ‘The Poet Went Blind.’

And this pulls him further and further from the people that he does write for, the ones who have loved him all along: his fellow workers in shop. The Leksikon mentions that while there were famous names at Rosenfeld’s funeral, the working class for which he wrote and of which he was part, were largely absent.

E.M. Lilien

His health takes another turn for the worse in 1937, but he only goes as far as the Arbeiter Ring’s sanatorium in Liberty, NY this time.

Shmuel Charney gives the year of composition as 1934, and says it was written in the sanatorium. The JCRS digital records actually note two stays for Leivick, in 1932-1933 and another admission in 1935, rather than an uninterrupted stay for three years — as noted by Gilman in his book about Yiddish poetry and the sanatoriums. E. Goldenthal, in Poet of the Ghetto, says the play was performed in Buenos Aires in 1936, but Charney makes no mention of this. Leivick confirms in Tog play was performed by Ben Ami in Buenos Aires and Chicago. Goldenthal notes that Rosenfeld went blind after his son died, was falsely reported to have died himself, and at the ‘posthumous’ acclaim, suddenly made a recovery to go on speaking tour — possibly what Leivick refers to in his introduction as ‘pretending’ is more of a psychosomatic reaction.

Rosenfeld bought out and burned many copies of his first collection, The Bell.

Acording to Amelia Glaser’s Songs in Dark Times, Leivick considers leaving America for the Soviet Union in his letters to his wife of the period, and Soreh responds that she is amenable to the idea.

According to the Leksikon, Rosenfeld was similarly summarily let go from his own paper.

Even the ‘striking in the teeth’ solidifies the ties with the real-world Rosenfeld; according to the Leksikon, the tag-line of his weekly satirical paper Der Ashmeday was ‘Smack the chin so that the teeth rattle!‘

Leivick becomes a permanent contributor to Tog in 1936, but no doubt the walkout from Morgn Frayhayt and the responses to it calling him a traitor in 1929 were still at the back of his mind.

As an aside, I wonder if Leivick didn’t feel that way himself sometimes — certainly he was as famous for his escape from Siberia as for his work. Did he even feel overwhelmed by the story? Or, as he certainly wasn’t ignorant of the importance of image, did he lean into it as Thornfeld does here, albeit ironically.