Zygielbojm’s Akeydah

‘With the detonation of his own life, he wanted to explode the great indifference toward the Jews in Poland’

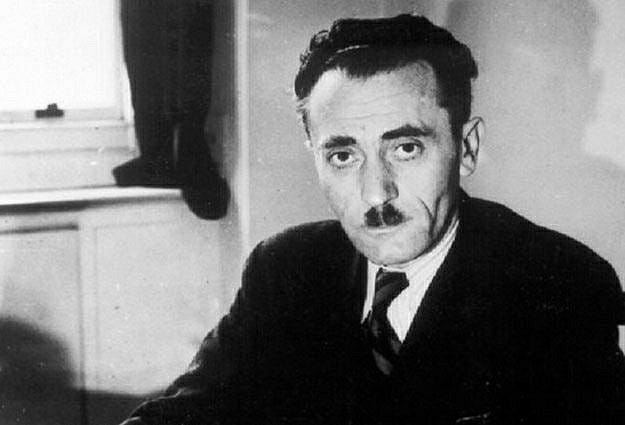

Szmul Mordko Zygielbojm was a Bund activist, politician and member of the Polish government in exile. He worked ceaselessly to try to impress upon other world powers the necessity of action against the Nazis. He committed suicide in London on 12 May 1943 when the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising was put down and the ghetto liquidated.

I really can’t do him and his gesture any justice in a short introduction.

Zygielbojm’s Akeydah

With the detonation of his own life, he wanted to explode the great indifference toward the Jews in Poland

Zygielbojm, suicide. I read his parting letter now. I read the letter — and everyone reads it — when it is already finished. The act of suicide — already carried out. Zygielbojm realised his decision. I look around me and ask: Have his death and his letter assailed the world as he thought it would be assailed? — Zygielbojm is already gone, he cannot turn to see and appraise the effect of his deed. But can we, the living, the close friends of his, appraise the effect of his death? Are we, those close to him — and who was close to him if not, first and foremost, the Jewish worker, the ordinary Jewish person? — are we those to whom his thought cleaved and in whom his heart had nestled, trembled? Are the Jewish workers of America — with the stress on America — shaken? And the wider world, the democratic world, the anti-Nazi world, against whom his word of protest was particularly aimed, has it, that world, heard his protest? — And another question: is anyone’s shock as strong as the beating of Zygielbojm’s heart was at the moment of his parting? Can anyone give an accounting of the martyr’s anguish and of the connection to the holy martyrs of our history which Zygielbojm attained in those minutes?

No, none of us can, at the present moment, give any answer and we certainly cannot give any answer to those questions regarding himself alone, to the extraordinary nature of his last moment, of his elevation and of his seeing the last moment.

This last moment of his will persist eternally in our consciousness. Like the last moments, for example, of Lekert. But regarding the questions which relate to us, the surrounding world, and particularly, indeed, the Jewish world in America, we do have something to say. The later effects of Zygielbojm’s sacrifice will, I am certain, be great. His last words, unusual in their simplicity and in their accusation, will be engraved into the heart of the world like a smouldering brand and they will sear and burn the heart of the world as that heart deserves. Fear not, there will still be enough heart in the world to lament in pain beneath the brand of Zygielbojm’s words. The heart of the world will, this time, not extricate itself from the responsibility of suffering, as it extricated itself after the first war. That heart will never recover again and will never be well if it does not bring itself to judgement before itself, if it will not read out the great and bloody indictment against itself, if it will not tally against itself all crimes and violence and murderous slaughter which it, the world, had perpetrated again itself with its own hand, and that the instrument of murder and violence — Hitler — was also its fodder. And in the text of that indictment which the world will set out against itself, amongst the words which will strike the world in the face with particular force, the place of honour will be occupied by Zygielbojm’s words which he left behind in his parting letter.

These are not the words of an arrogant man, who even in his last moments put on affectations; nor are these the words of spite, of embitterment or of personal weariness. They are, through and through, the words of great responsibility, of the earnest conscientiousness of a revolutionary who, in a world of abasement, does not want to be the debased, who wants to follow his call from that socialist power and from that socialist purity and worker’s simplicity which almost do not exist in today’s world, but existed in the days of Hirsh Lekert. That pure idealistic awareness of struggle against evil and and crude might which attains its highest holiness and truth precisely then, when a man gives away with full readiness and with full clarity the most precious thing which he possesses — his own life.

There is also, in that act, protest, a belief in the purely ideal redemptive power of humanity (for if not, there would have been no sense to wish to affect them through sacrificing oneself), Akeydah, as well as revolutionary pathos.

But burned out people, in whom both the truth of socialism and the sacred romance has transformed into careerism, into opportunism, into machined leadership, they are not capable of feeling the pathos, the Kiddush Ha-Shem and the Akeydah act which are present in Zygielbojm’s sacrifice.

They are not capable, and like them — the official leaders of the word, the governors, the premiers, the presidents.

And indeed at them, first and foremost, Zygielbojm’s protest was aimed.

And at the ordinary person in general, and at the ordinary Jewish worker in particular, Zygielbojm had, apart from his protest, also aimed his act of martyrdom and his Akeydah anguish. He joined, in death and in holiness, the Jews of Warsaw and Lublin and had, in joining with martyrs of Warsaw, aimed his anguish and his solidarity in destruction at us Jews in America, at all of us, against all the groups and parties, against the entire Jewish spiritual and material world in America. And most of all, I imagine, he aimed his Akeydah anguish at the Jewish labour movement here, at the Jewish socialist world here, at all the Jewish unions of which he considered himself part, as blood of their blood and flesh of their flesh. He had a right to want to see in them (as he was accustomed to seeing in his home in Warsaw) active people’s fighters and responsible bearers of the people’s terrible fate — and he saw, in Jewish labour here, lifeless movements, paralysed factions, sunken into the sweet softness of comfort, labour leaders who extinguish beneath the light of power and proximity to government, Jewish culture’s sense of inferiority and assimilation.

He perceived, and rightly so, that American Jewish labour, in all its shades and directions, without exception, had not risen to its socialist and Jewish nationalist role and, with its own hands, it gambled away its nationalist role in the present terrible period for the Jewish people. It does not become shaken. It is not shocked. It shows no trace of deeper emotion, of longing for sacrifice, of exaltation of death.

He writes in his suicide letter: ‘I can neither remain silent nor live while the remnants of Polish Jewry, whom I represent, are murdered. My comrades in the Warsaw Ghetto died with weapons in hand, in final heroic resistance. It was not destined for me to die like them, together with them. But I belong to their mass graves. With my death, I want to express the strongest protest against the passivity with which the world looks on and allows the Jewish people to be eradicated —’

Can there be any greater accusation and, at the same time, a greater act than an Akeydah? He belongs, he says, to their mass graves. He would rather be with the murdered before seeing how the larger, non-Jewish world ignores the slaughter of our people, and how the Jewish masses in America do not begin to stir the world.

He had enough examples of the world’s indifference and of Jews’ own inaction. He only needed to recall how mocking, for example, it had appeared on the day when there was proclaimed, a short while ago, a national Jewish day of mourning, when masses needed to spontaneously fill the streets, truly interrupt their work, close shops and carry outside, openly, under the heavens, a demanding outcry. Not to go out alone, but also to call upon the entire American labor movement. Call the American labor movement to a protest-congress, to an action-congress. As that call is properly organised. And it is no impossibility at all that such an all-American labor congress would be able to be called in the name of saving the Jewish people, in the name of warning Hitler. If it were said, if the Jewish labor movement here would stand on the level of its role regarding its own people. But that day of national mourning proved precisely the opposite. If one should accept the excuse that the day of mourning then was called without proper preparation — it’s still an excuse, a formulaic one, and it proves firstly that the Jewish labor movement here no longer possesses any deep nationalist sentiment, any revolutionary emotion. The Jewish workers did carry out a bit of a ‘stoppage’ in the shops on that day, but nothing more then mockery and self-deception came from it. They carried out a so-called fast for ten minutes. No more. And — barely waited for the ten minutes to finish. And somewhere on East Broadway several hundred Jews did go with calls of protest and cries of Shema Yisroel and truly mourned and bewailed the Jewish catastrophe. These were a couple hundred frum Jews. Their hearts did speak out. They carried a Torah and lamented. And the cold wind tore at their coattails and they resembled a small flock of hunted sheep. How could the look otherwise when all the people remain in their houses, in their shops, and do not go out to join in their people’s lament?

Yes, Zygielbojm had needed only to recall this. And he certainly, I am sure, recalled this. And there certainly also stood before his eyes the fact of how the entire anti-Nazi world had raged at the story of Lidice and how the same world did not stop when a hundred Lidices happened in Poland. And he had certainly asked himself: How would it be if the Nazis murdered out in Poland, not two or three million innocent Jews, but two or three million innocent Americans or English — would America and England also then weigh and measure their reactions towards it, and would they also then continue to keep their gates barred before those who were able to be saved? Would they also then, under the excuse of ‘white books’ keep the borders of the land of hope slammed shut? Would they also then seek all sorts of pretexts in order that opponents might not say that it is an American or an English war?

Yes, Zygielbojm certainly asked these questions at the hour of his fateful parting. In that hour, the questions were not simply quixotic battling of windmills, but hard, stinging stones which struck the head of the honest, devoted, pure, prepared for sacrifice, Zygielbojm, and he struck back with the only weapon which he possessed — with the detonation of his own life.

He belongs to the Jewish mass graves, he said in his parting letter — with this, he proved that he belongs to the Jewish saints and martyrs. — To whom do we belong?

— H. Leivick, 13 June, 1943, Der Tog

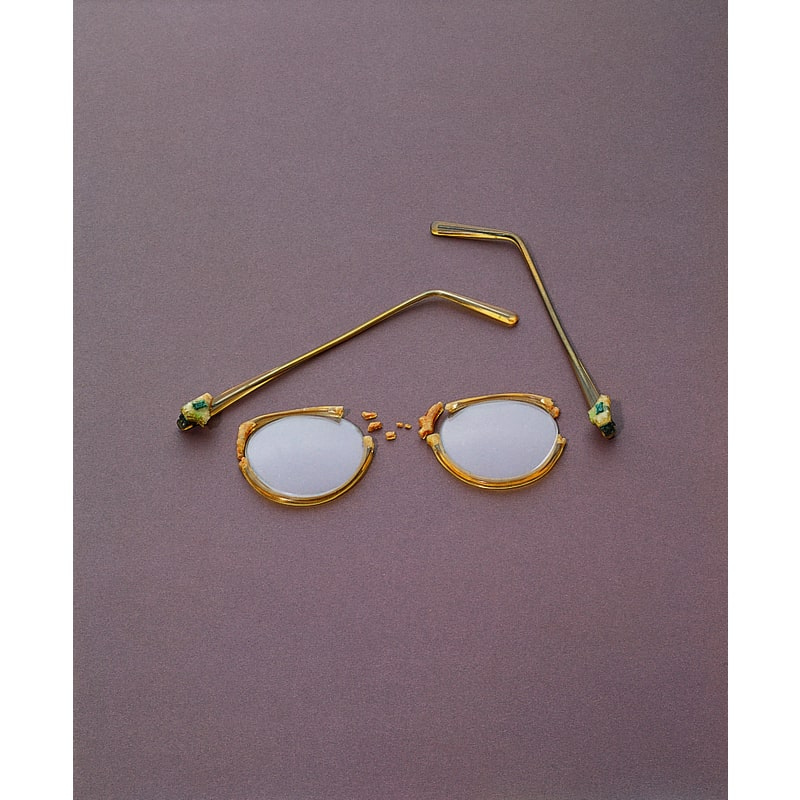

Zygielboym’s glasses, From the Archives of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. 9149.97

I have left ‘Akeydah,’ as per my usual, untranslated. You could, perhaps, translate it as ‘sacrifice.’ But I am very hesitant to do so with Leivick because of everything that the word entails for him.

You might even think back at the end of this essay to the play Akeydah and Satan’s question of ‘will it at least be a lesson to them?’ Leivick asks the same question here, a decade later — will Zygielbojm’s death be a lesson to all of us?

If you had to reduce all of Leivick’s work to a single, solitary image or symbol, it would be the biblical Akeydah: the binding and near-sacrifice of Isaac. He plays it out continually, in multiple configurations, time periods, casts, outcomes. And I think to translate it would be to lose some of the depth of meaning and the power intended by it. It’s a sacrifice, a binding, a commandment from God, a test of faith, a foundation, seeing and empathising with the incomprehensible suffering of millions through the lens of a single individual.

It goes all the way back to a day when Leivick was seven and wondered, in tears, what would have happened if the angel had been a moment too late to stay Abraham’s hand…

As this is a work of rather unadorned translation, I wish to note quite strenuously that I do not hold the rights to the original and my own translation is presented here from my own scholarly interest (and hopefully yours). All mistakes my own.