As we mark International Holocaust Remembrance Day on the 27th of January

I’d like to take a moment to recall the day of remembrance that simply…vanished.

It was never widely adopted, never spread beyond the confines of the American Zone in Occupied Germany, and simply ceased to be as the remaining Jewish Displaced Persons camps were consolidated and gradually closed.1 But briefly, there was the 14th of Iyar, chosen by survivors, sharing its date with ‘Second Pesach’2 and roughly coinciding with the anniversary of the end of the war.

It’s one of the events which is, in fact, not in Leivick’s book recording his trip to the DP camps, With the Surviving Remnant (1947) — not the meeting which decided it, nor the actual commemoration itself in Munich. He was present at both, however, in the company of his co-delegates (for whose books I also have working translations), Israel Efros and Emma Schaver.

Here’s Efros on the meeting, from his book Homeless Jews (1947):

We today attended an important sitting of the C.C. (Central Committee for the Liberated Jews in Bayern) under the chairmanship of Dr Zalman Grinberg.

Two matters were on the order of the day.

Firstly, it was a year since the liberation of the surviving remnant. They needed to create a new day on the Jewish calendar which would immortalise the sorrow and the joy, a day which would sail up every year like a ship into a harbour, offloading heavy, large, sacred memories, sailing away again and somewhere, on the other side, loading itself again to come back next year.

We have lived through dreadful years and we are full of testament, of commandment, of ‘remember!’ for the coming times.

Remember, all you coming generations, what Germany did to us and what exile can bring about.

A new ‘remember what was done unto you’ bursts from us with a cry, and we cannot and ought not hysterically suffocate it.

And who has a right to give an opinion on such a day of remembrance? Who has the authority to sanctify such a day for the whole nation and for all time?

Not the greatest rabbi and not a hundred rabbis, but they, the ones who suffered through it, the few remaining, who accompanied the six million on their last road.

They now proclaim the day, the 14th of Iyar, and we are witnesses.

The room is dark. People sit silently. And the surviving remnant gives birth to a day.

Congratulations to you, Mother, on the birth of your youngest child. You should raise him in joy, in Eretz Yisroel.

Only there is no name.

They spoke about ‘Yom Zikaron,’ ‘Dror,’ ‘Sh’erit.’

They could not decide.

And the painful truth is that this child doesn’t have a face.

What sort of creature is it? A sorrowful day or a holiday? A day of weeping or a day of joy? Purim or Tisha B’Av?

One still doesn’t know. The situation of the Jews in Germany does not allow one to take out the Purim groggers and rattle them.

The date, however, is here. A birthday is born.

The child itself will come in time.

And they will write a new ‘Al Hanisim,’ a new suitable Megillah, and ritual ceremonies will dramatise the pain and the joy, the suffering and the heroism, the sanctification of the name and the miracle.

Meanwhile, there is the 14th of Iyar. The name — the same. Just as Kaf Sivan, First of Tevet, Shivah Asar b'Tammuz and Tisha B’Av.

Borrowed from Yad Vashem. In UNRRA uniform, Efros at left, Leivick hatless, in Germany in 1946.

And here’s Emma Schaver on the meeting, from her own book, We Are Here (1948):

A Yahrzeit for Generations to Come

Meanwhile, the Central Committee asked us to be guests at their weekly lunch. There were representatives from all the bodies and agencies that participated in helping the surviving remnant in all sorts of forms. There were representatives from the Joint, the Jewish Agency, the Jewish World Congress, Vaad Harabonim and others. The most important question of the order of the day was when to set a day for yahrzeit, a date that might remain for generations to come as a memorial to the liberation from Hitler’s regime, and how should the day be honoured; if it should be in expression of sorrow or, conversely, in joy? There were opinions that there was already enough suffering and as soon as the Lord of the World helped and they were free of the Nazis, they must celebrate the yahrzeit like a great holy day. There were, however, others, who held that that misfortune was so great that the yahrzeit must absolutely be observed in sorrow, as a memorial to the sacred and pure who had so pitilessly died. At the end, all arrived at a single decision, that they, being so to close to the events, could not now decide the exact character of the anniversary. Life will do it. Now it is only important to assign one day in the year when the yahrzeit ought to be in effect for the whole Jewish world.

The yahrzeit was assigned as the day of 14 Iyar.

They telegraphed several Jewish centres about this, as well as to America.

Emma Schaver, borrowed from Jewish Women’s Archive.

Where was Leivick in all that? Gabriel N. Finder, in Between Mass Death and Individual Loss: The Place of the Dead in Twentieth-Century Germany, notes that Leivick came down on the side of those encouraging a solemn holiday, to be guided by the survivors and a sensitivity to their experiences (rather expectedly).

And there were enormous commemorations, attended by thousands of survivors in places like Munich (back to this in a moment) and in Landsberg. The next year, Finder says, they even recreated a death march as part of the ceremonies marking the day — those rituals that Efros foresaw would arise. But it was never widely taken up outside of the DP camps, those initial telegrams getting little, if any, reply. Finder posits that if it hadn’t been ignored, it certainly would have been usurped intentionally by other interests.

While it is fair to say that other days of memorial were created to serve different, oftentimes political ends, it would be wrong to say there was no political flavour to the original. For that, we return to Munich in 1946 and that first official commemoration.

From Yad Vashem

Here you can see the cultural delegation to the DP camps with Emma Schaver at centre in black, Leivick on her left and Efros on her right. They’re sitting in the Aula Maxima of Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich. Off to the right, you might notice a framed portrait between two candles and two flags, and Efros tells us exactly who it was — Theodore Herzl: 3

We sit at a long speaker’s table in a large hall in Munich and two thousand Jews sit in the auditorium and around in the galleries.

It is a marvellous hall, with Byzantine mosaics, paintings and Latin inscriptions. The demon stole beauties and truths and adorned his abominable body with them. He himself has created nothing.

Why should he create his own if he wants that one should think that he is almighty?

It give me the impression that I am in a idolatrous temple. What sort of impure speech the hall has heard! What savage parades with shrill screaming went on here! The speakers and the parades are disappeared, but the victims of their raging remain. See, how they sit with dry eyes and stoney hearts. And see, how from the stage, from between two electric lamps, the great black eyes of Dr Herzl’s picture gaze sadly!

Dr Zalman Grinberg stands up and holds a short opening speech.

‘The surviving remnant want one day of the year set as a headstone in the annual calendar. The day is the general yahrzeit for the known and unknown victims, and at the same time the day in which the remaining, miraculously saved Jews should recall and hold sacred in their memories the extraordinary miracle of their individual liberation.’

Correctly formulated: tombstone and miracle.

Jews do not operate with bronze or marble, but with time. And they do not live in the three dimensions of space, but in a single dimension which stretches forever and ever. All of our historical monuments are little knots in our dimension of time.

(From Israel Efros, Homeless Jews)

Here’s what the hall looks like now:

From LMU

What, exactly, did Leivick have to say on the day? I don’t know yet. But I do know that the two men both did speak and Schaver, once again, sang:

The date of the 14th of Iyar arrives, which is proclaimed the yahrzeit of the liberation. In Munich a great commemoration was observed. We were invited, as well as governmental representatives. At five o’clock the affair began. It took place in the university auditorium. The hall was packed. On the stage stood a Yizkor tablet, and around it a guard of youths. The opening came in the form of a declaration which Dr Grinberg gave in Yiddish and English. Then they played ‘Hatikvah,’ and given that the American military forces were represented, the ‘Blue-White Orchestra’ also played the ‘Star Spangled Banner.’ A chazan recited an El Malei Rachamim and in the hall there was a movement. Again the wellspring of tears had opened for those who mourned their nearest and dearest.

The chief rabbi of Bavaria spoke in Yiddish. Dr Hoffman, the representative from the Jewish Agency in Jerusalem, spoke in Hebrew. A colonel from the American occupation army spoke, naturally, in English. Then, in Yiddish, the representative of the Central Committee, Mr Traeger, spoke, Leo Schwartz of the ‘Joint’ spoke a couple words in Hebrew, then in English. The most moving speakers were Dr Blumovich, in the name of the partisan group, a representative from the Munich committee, and Mr Eisman, in the name of twenty-three survivors from the hell of Treblinka. All spoke in Yiddish. The orchestra played ‘Eli, Eli,’ Leivick and Dr Efros spoke, and I closed the impressive yahrzeit-conference with three songs, Yehuda HaLevi’s ‘Sea Song,’ a song from Eretz Yisroel, and ‘Kol Nidre.’

(from Emma Schaver, We Are Here)

From Yad Vashem. Leivick, in UNRRA uniform — he disliked it — speaking in Munich at the first 14th Iyar commemoration. Dr Grinberg at left, Efros to the right of Leivick.

My usual below-the-line notice. I don’t hold rights to the material here and present it out of my personal interest. If you do own the rights and want things removed, let me know. All translations and mistakes my own unless noted.

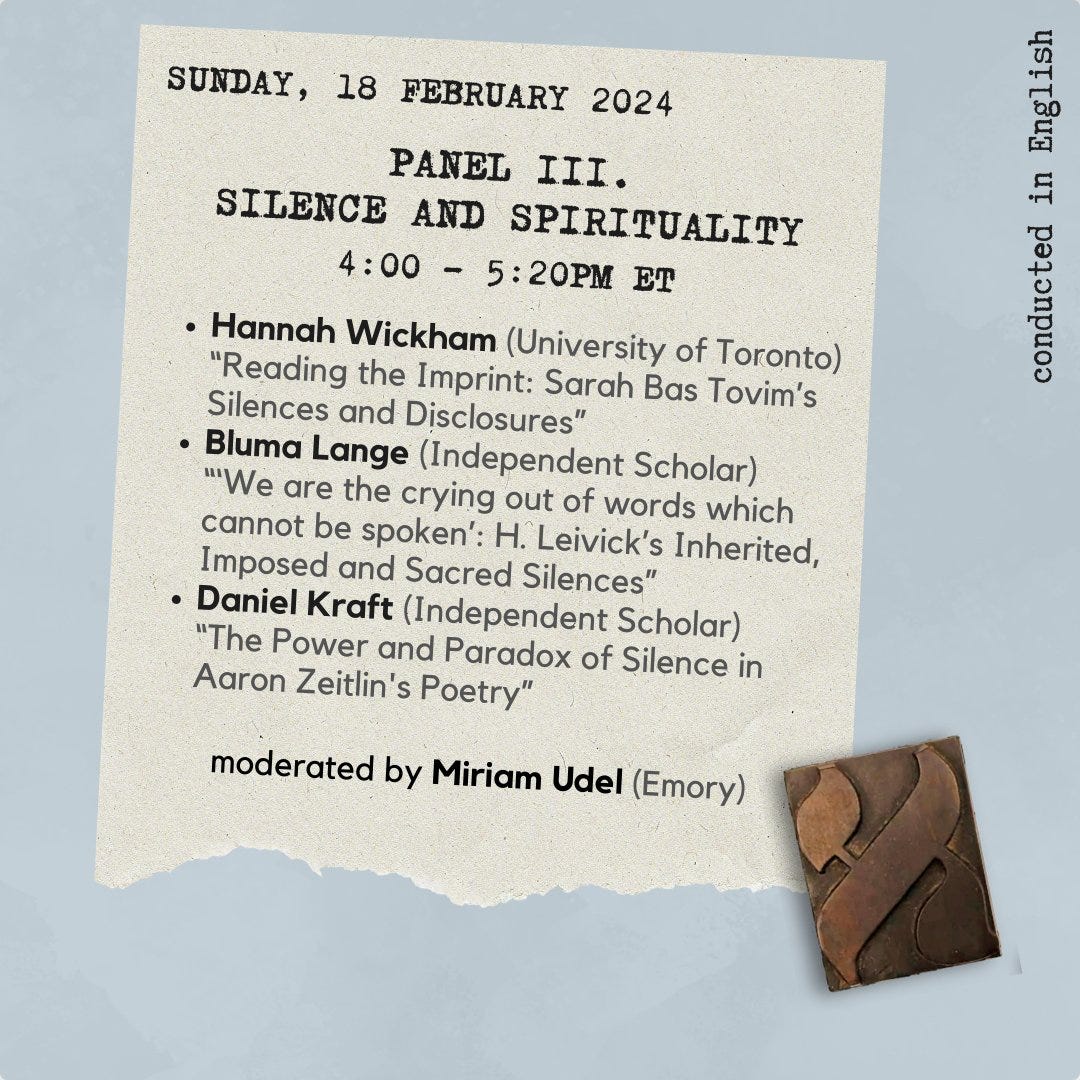

If you’re interested in what I have to say about Leivick (I’ll suppose you are if you got this far) I’ll be presenting a short paper on Leivick at Farbindungen 2024, a virtual Yiddish conference.

Foehrenwald was the last, shutting in 1957.

Second Pesach/Pesach Sheni is essentially another go at Passover, if you were travelling or ritually impure to offer a sacrifice.

Efros, who mainly worked in Hebrew (Homeless Jews, and the articles it’s drawn from for Morgen Zhurnal, being his sole foray into Yiddish), made aliyah in 1955. Schaver, too, had a continued close association with Israel — her book was also published in Hebrew.