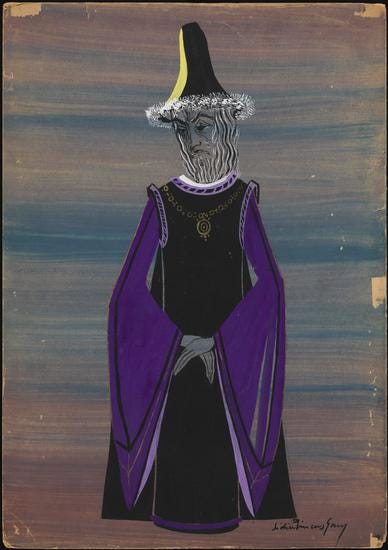

The Maharam, Costume design for Maharam of Rothenburg, from the Museum of the City of New York, Accession 65.83.8.

If trauma can move an individual through time —

send us back and forth to a personal past and the present — by means of the unconscious, then Maharam of Rothenburg (1944) is an exercise in what happens if we extend that to the collective unconscious of a traumatised people.

H. Leivick, Maharam of Rothenburg, 1945.

Leivick himself moves fluidly between different, sometimes fragmented, versions of himself. Often through the medium of trauma or an object or image linked to a traumatic event. For my purposes here, I’ll focus on his ‘present’ self and past self.

In his speech ‘The Jew — The Individual,’ Leivick identifies some of his own, personal doors between past and present, a day comprised of several events he characterises as too much for most adults individually, but which he had borne as a Jewish child all on the same day. The story of the Akeydah — the second of the events he lists — being the most frequent of Leivick’s ‘doors’.

The ultimately fatal burning of his sister is another of these personal ‘doors,’ I think, given his reaction to burned survivors in the DP camps: he abruptly ends one encounter, tells the reader that he physically turned away from a second, unable to recall where it was he had seen burns like that before (both earlier in the trip and as a child).1

Leivick’s arrest in the night is still another door — he recounts in essay being frightened when Mani Leib arrived at his room in the middle of the night and being dogged in New York by the thought the door would be kicked in and he would be arrested again in ‘Clouds Behind the Forest.’

1944’s Maharam of Rothenburg gives us a few such events to join our 13th century timeline with our 20th century one — doors that join events in the life of the Jewish people. The burning of books in a public square. A captivity from which one cannot be redeemed. A false messiah or two.

And as Leivick has claimed the Jewish child had the extraordinary ability to bear more than a gentile adult could imagine, so the Maharam tells his jailer he cannot comprehend the Jewish ability to turn this trauma into a an asset, this ability to move through time.

The same Jew — in this case, Leivick himself — can stand at Sinai, following the Exodus, just as well as stand atop it in an icy courtyard in Belarus two thousand years later. They can be imprisoned in Mainz in 1298, Butyrka in 1912 and Dachau in 1943 at the same time. And sit in an apartment in Washington Heights in 1945. And probably set foot on the moon, too. Certainly greet the Moshiach at the end of the world and herald his arrival.

Every Jew, Ahasver, the Eternal Jew, tells Daniel, is a legend. A nation of sages, of martyrs. And, it seems, time travellers. At least through the medium of collective trauma.

To return to the idea of a Jewish child being able to bear the unbearable for gentile adult, even Leivick’s imagined Hitler in With the Surviving Remnant, who is concealed under his bed in Ainring, in one of the more surreal episodes, wants to know the secret of Jewish suffering — how to suffer and not give in to hellish torments. To bear it in a superhuman way.

Looking at the Maharam’s own kinah — written after witnessing the burning of a good portion of the printed Talmuds in Europe — we’re on familiar Leivick territory and it’s easy to see how the Maharam appeals.

Leivick’s fire is often one of two halves, the generative and the destructive. How can something created in holy fire, the Maharam’s kinah asks, be destroyed by mere earthly fire? Leivick is never unaware that the fire he sometimes celebrates as beginning or sustaining (‘Ballad of the Desert,’ part of ‘In Fire,’ his mother’s oven) and potentially liberating or defining (Different, Tsarist Katorga) can also be a hideous force of destruction (the other half of ‘In Fire,’ the death of his sister, etc).

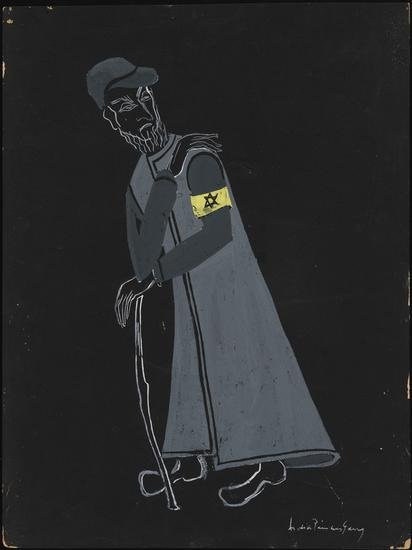

We have another means of travel, in addition to the ‘doors’ of the traumatic events themselves: With a guide. Leivick references Dante’s circles of Hell in With the Surviving Remnant and we’re about to have that sort of tour guide here — instead of Virgil, the reclaimed Eternal (or, Wandering) Jew. He’s a sort of personification of that collective Jewish unconscious. Because everywhere there are Jews, he says, there he is. He’s lived through all these events, seen the patterns, knows where the door will open — straight into a pogrom, like always.2

We aren’t ever entirely free of our past, no matter how we may wish to liberate ourselves from it.

I’ve touched previously on Leivick’s chain symbolism — it’s not the glorious goldene keyt, even if he is proud to wear ‘the chain of [his] yichus,’ and new moments always owe some part of their existence to the moments which came before (as he says in Tsarist Katorga).

And Daniel tells us right at the beginning that he has already read enough Jewish history to know it’s all suffering. There are shades of other Levickian characters in this, such as Professor Shelling who wants to escape this history and this suffering, this chain, and spare his children it.

Shelling’s is briefly interned and released again. Daniel, however, is in Dachau for keeps. And while he’s there, his own trauma (in the form of Ahasver) whisks him off into his past — that of the entire Jewish people.

Daniel is constantly tempted to tell the medieval Jews where, exactly, all this is heading — breaking that most basic rule of time travel. He not only knows what will happen to the Maharam, but what will become of the Jews of Germany in 700 years time. And in this, he and Ahasver also introduce to the play the idea that something must be held back, so as not to make things worse — flirting with that other great theme of time travel, that maybe the time traveler has always gone back, will always make the same mistakes, thereby setting up the future that he is trying to alter.

Seven hundred years is nothing, Ahasver tells Daniel, his own perspective on time and fate altered by having been witness to so much of it. He’s rather blasé. An attitude, he says, that others only gain when they know they are at the end; the attitude toward the world, life and death that their gain when they pass through the ‘final door’ and touch God.3

From Dachau in 1943 to Mainz in the 13th century is a single step, according to Ahasver. And so it might be, if you can see the totality of history.

Daniel and Ahasver arrive immediately post-pogrom — Daniel recognises this, and the antisemitic song the pogromists are singing as what they are: interchangeable with those of his own time.

H. Leivick, Maharam of Rothenburg, 1945.

History is a series of circles, patterns. It’s always five o’clock somewhere and pogrom — somewhen.4

And the pogromists, too, live by this notion: Hate will come tomorrow, the day after tomorrow. It can only be postponed. Tomorrow, in terms of being any different, is an ugly lie — as the Chronicler in Wedding in Foehrenwald will tell us in a few years’ time.

Ahasver, the Eternal Jew, Costume design for Maharam of Rothenburg, from the Museum of the City of New York, Accession 65.83.4

To be continued… and a further note: all the costume designs reproduced here are from the Folksbeine production in 1963-4 and are from the website of the Museum of the City of New York.

Sandor Goodheart includes the burning of Leivick’s younger sister, Tanya, in this day, considering it the fourth event he blocks out of the recounting, as he lists three events but says there are four. I think it’s fairly clear that while it occurred at roughly the same age, it wasn’t the same day. Reading the description of the day in In Tsarist Katorga, the fourth event might well be his arrival home, bloodied and seemingly in a fever. The long description of the night his sister was injured in Y. Pat’s interview doesn’t square with Tsarist Katorga’s more elaborate description of being punched in the head, unsettled by the story of the Akeydah and sticking his tongue to a frozen pole. He was also, by the time of that speech, talking and writing about his sister’s death in other fora, so no reason to necessarily assume it was completely repressed at that point.

I am tempted to think here of Leivick’s own moving backward through time during an attack by Germans on the gates of Feldafing to his own childhood in Belarus decades before. As for a guide, it is tempting to remember here the Devil showing Isrolik the evils of Europe from above in Mendele’s The Mare (also a story of transformation, a bit like Leivick’s ‘The Wolf’) which is, in turn, rather similar to El diablo cojuelo, where Asmodeus shows the student who has released him the inner lives of the apartments of Madrid. Ahasver shows Daniel not just across a city or continent, but across centuries.

Being touched by God — as Isaac feels the wing on his face at the Akeydah in In the Days of Job — is part and parcel of chosenness. It’s just a matter of when that chosenness is confirmed, I must suppose. And, as we know from Leivick’s other works, chosenness is not always the happiest of lots during life.

Also in evidence in Leivick’s ‘Ballad of the Desert.’ Every Jew was at Sinai, personally taken out of Egypt. But every Jew, including Leivick’s father and Moses himself, has a turn wearing the pointed Judenhüt, the yellow star or both in that long poem.