My subtitle here is taken from Cynthia Ozick’s translation of ‘Open, Gates’ — she calls her version ‘Sanatorium,’ which provides what may be missing context if you are unfamiliar with the circumstances of H. Leivick’s being in Colorado: treatment for TB.1

It’s a banger of an opener to 1937’s Lider fun Gan Eyden (Songs of Paradise, Songs from the Garden of Eden, etc, you get the picture). Here’s the stanza in question, from Ozick’s translation:

From Greenberg and Howe’s A Treasury of Yiddish Poetry, 1969

The covers of the book open, the gates of the sanatorium open, and we almost find in this first poem a table of contents. We do, in fact, visit hospital, prison and ‘some monkish place’ in the course of the book. And it’s the last of these I’ll be looking at — the monastery.

Ernest B. Gilman’s Yiddish Poetry And The Tuberculosis Sanatorium tells us that the sanatorium might just as well have been a monastery in its expectations of total celibacy from the patients. There were apparently a lot of ‘cousins’ who came to visit…and you could be kicked out if caught! I’ll note that Gilman doesn’t like Ozick’s giving away the game of exactly what gate Leivick/the speaker stands before too early in the game, but she doesn’t have the benefit of the whole book following to clarify — or obfuscate — that. I have my own quibbles with Gilman, but I’ll get back to that.

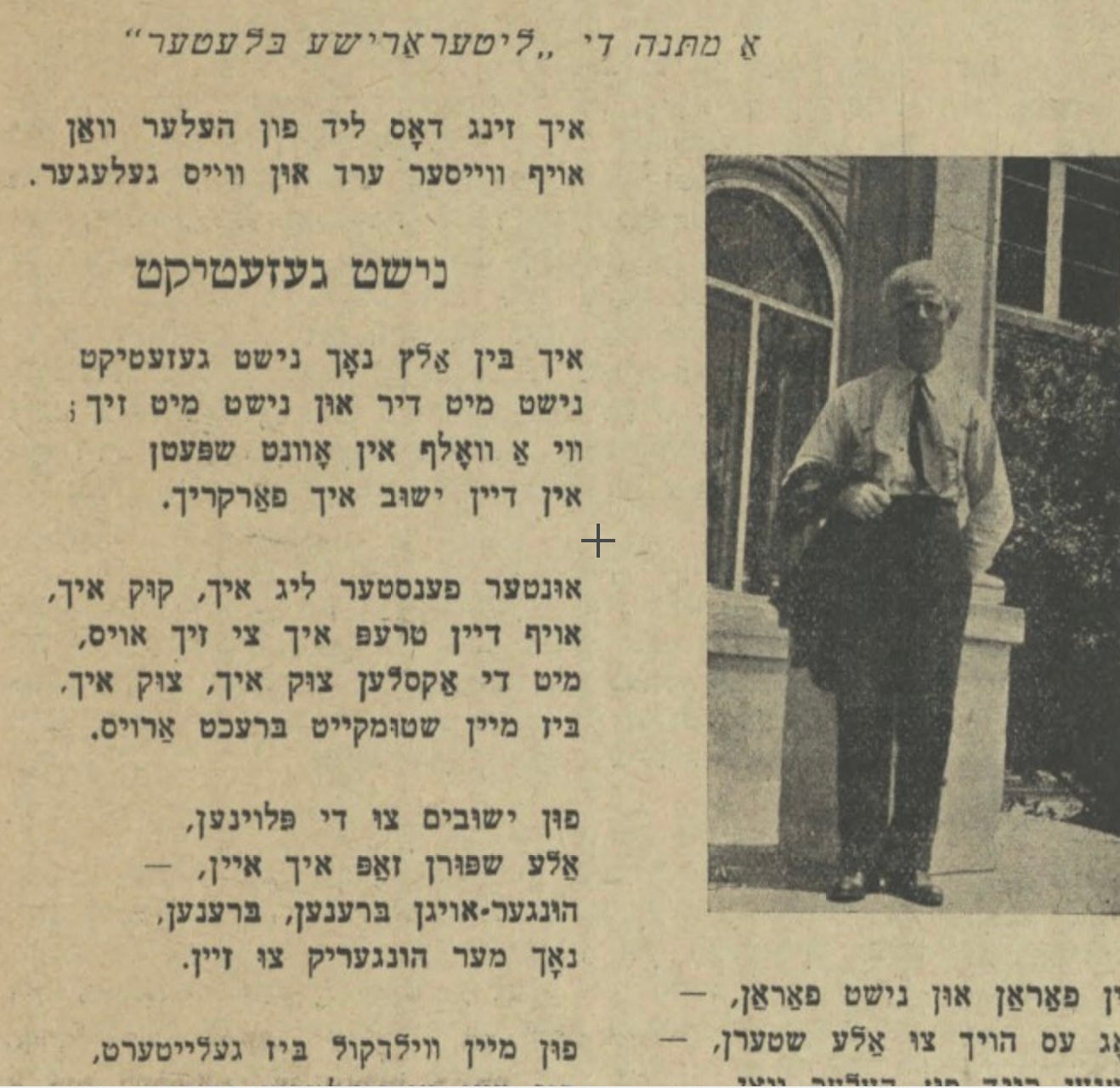

The man himself posing at the JCRS Sanatorium in Denver, alongside some of the ‘Spinoza’ cycle of poems from Lider Fun Gan Eyden. From Literarisze Bleter.

First and foremost, we are struck in Lider fun Gan Eyden by ‘hospital.’

‘Prison’ remains far more elusive and allusive in the collection, barring a poem set on the first of May in a Russian prison. Leivick’s own ‘prison-like nature,’ as he calls it, and the metaphorical prison of illness are far more prominent here than anything of his actual prison experience.

But of ‘hospital,’ we have fellow patients, death, the reek of carbolic, hospital grounds and gates, the Rocky Mountains, the mortuary, bed after bed, the dining hall, the nurses, the orderlies, the local Jewish cemetery filled with TB patients, even the white rabbits used for medical testing…it’s a rather full picture.2We even have a second sanatorium mentioned: Liberty, in upstate New York.

So where does ‘monkish place’ come into play?

A little ways into the book, after a spate of poems mostly rooted concretely in the world of the hospital (‘Darwin,’ with its imaginary foray into the jungle as an orangutan, is a wonderful exception), the reader encounters ‘Songs of Abelard to Heloise,’ a cycle of six poems composed in the persona of Peter Abelard, addressing his former student, collaborator and wife, Heloise d'Argenteuil.

I’ll let Leivick himself tell you about the two of them.

Abelard— a famous theologian, philosopher (also, in younger years, troubadour) at the beginning of the Middle Ages in France. Heloise— his lover. A man of talent and steadfast character. Because of intrigues surrounding them in society, Abelard and Heloise — devoted to one another in their love— were forced to see out their lives divided, in separate monasteries. Abelard’s work was publicly burned because of its unconcealed Epicurean thought. Apart from this, a shameful operation was carried out on his body. Notwithstanding their separation, Abelard and Heloise did not cease to love and yearn for one another. Their fate has remained for all time as a symbol of martyrdom and unbetrayed love. That which was not destined for them in life — to be united— death granted to them. Upon their deaths, the both were entombed in one grave.

Why Abelard and Heloise? I’m not entirely certain. Yes, there was surely something of the monastic life recalled in the sanatorium regime (and back home, in New York, for the partner left behind) and there was, perhaps, yearning for his own wife encoded in there, the empty place in what should be a conjugal bed.

But why them in particular? Perhaps it has something to do with the reading which Leivick himself was doing at the sanatorium — it’s certainly what gets us to Darwin, and also what takes us to Spinoza: in addition to Spinoza’s own lung ailments, Shmuel Charney notes Leivick wrote to him during this period about his reading Spinoza’s Ethics and Theological-Political Treatise (preferring Ethics). Spinoza himself can almost be thought of as a sort of Jewish monk or hermit, entirely isolated, devoted to the works of his mind and the presence of God in everything.

I’ll also point here to the letters exchanged between Leivick and Mani Leib which are quoted in Ruth Wisse’s A Little Love in Big Manhattan and Leivick’s remarks reprinted there about how while Jews don’t have monasteries, the sanatorium was the closest thing in America to the Old World houses of hisbodedut — solitary Jewish meditation.

Peter Abelard is certainly someone Leivick could have encountered reading philosophy (see Leivick’s mention of Epicurean thought above) and was unusually ‘generous’ towards Jews for a Christian clergyman of his era.

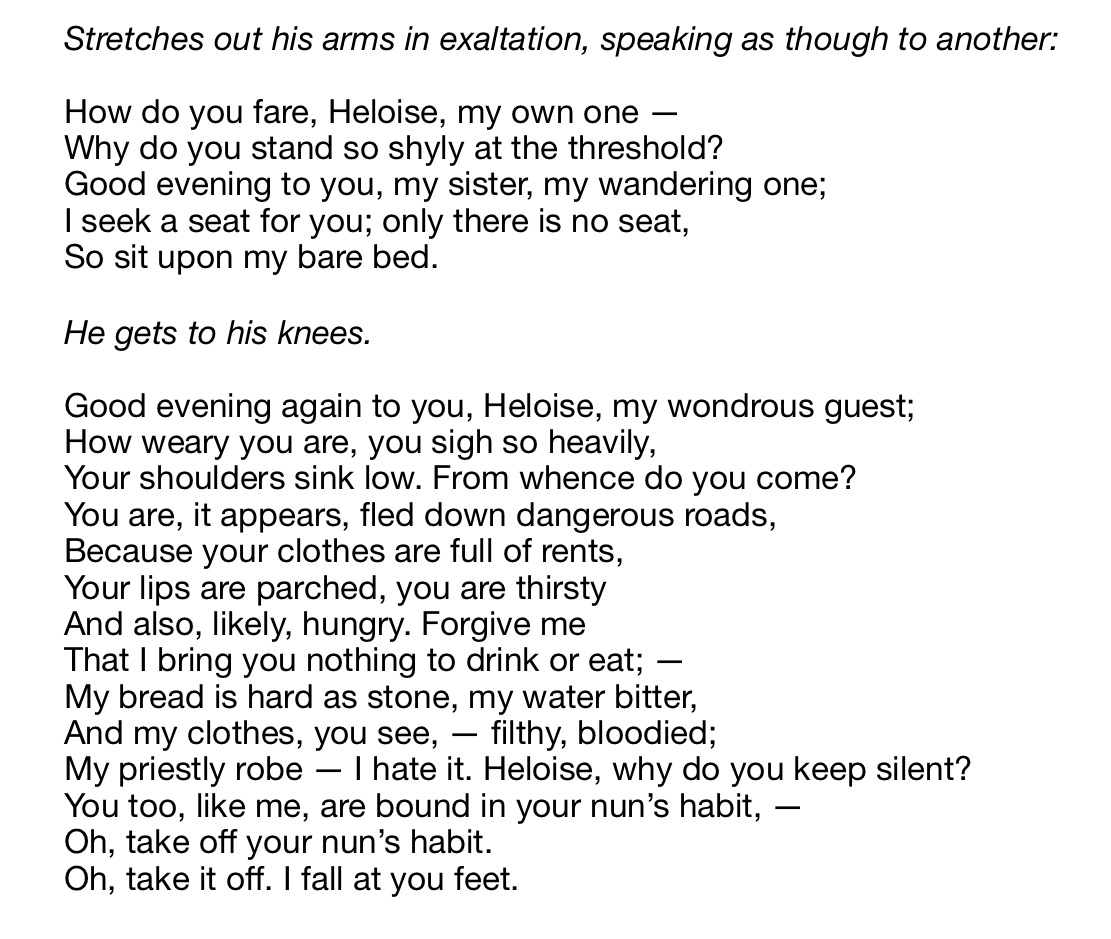

The set of six poems from Abelard to Heloise do touch upon certain biographical points. And, my goodness, are they beautiful. Leivick can be rather restrained, I find, with the romance3 — or even plays up how befuddled it makes him/his speaker, causing him to confuse knife and fork — but when he goes full throttle, it’s usually absolutely gorgeous. Here’s the second poem of the cycle:

But these poems also have a certain lack of clarity to them, details not necessarily drawn from anything that Leivick was reading at the time or from a standard biography. For instance, in the fifth poem of the sequence, ‘Holy Day,’ there are references to a knife.

There are other obscure, slightly strange images, as well, such as Heloise coming to Abelard dressed as a man. Where do these come in?

This is, in fact, a prime example of reading what Leivick has going on somewhere else for a little bit of explanation; they’re drawn from his play written at roughly the same time, Abelard and Heloise (1935, published in Zamlbikher in 1936).

Here, in this excerpt from Abelard’s dialogue, you can see how some of the phrases and images that appear in that second poem of the cycle above also appear in the play: His inviting Heloise onto his bed, dryness, the removal of the nun’s habit. The poems essentially function as distilled versions of the play.

Abelard and Heloise is rather a unique play in Leivick’s dramatic work, given that it’s the only one without any Jewish and/or Biblical characters in it at all.

Which again begs the question why and, more importantly, how?

To Be Continued…

Why do I always come back to the sanatorium works? It was an incredibly productive period, it’s where I came in, and they’re some of the most personal works to me. And this is a diary, after all, even if a poor one.

A picture that make a bit more sense, incidentally, if you know a bit about the JCRS, like their herds of cows. There’s a film roughly contemporary to Leivick’s stay there, which can be seen here.

Early work sets him up a bit as a ‘frosty’ character — quite literally. But Leivick tells you himself there’s hot blood under the snow, and does eventually scrape it away (‘Song of Myself,’ Lider fun Gan Eyden)