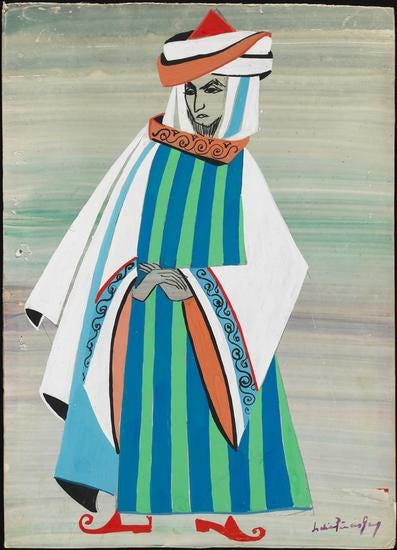

Rokhl, Costume design for Maharam of Rothenburg, from the Museum of the City of New York, Accession 65.83.3

There is yet another factor in the ability of Daniel to essentially walk out of Dachau:

He’s entered the liminal space of sleep. In this place, the rules and constraints of the waking work are blurred or disappear entirely.

Leivick describes several moments both in poetry and prose where this occurs to him personally — not only in sleep, but while seemingly awake, he is able to pass through walls, move as if flying, see his ‘other self’ either through physical means (a portrait, a reflection in a window) or by seemingly moving out of his own body. And we’ve seen his characters enter these dream states before, too. Notably, it’s Leivick’s Golem who dreams in the by-title of his 1932 sequel to 1920’s Golem.

Shmuel Charney explores the significance of what title Leivick’s plays carry while discussing Poor Kingdom (Orame Melukhe) — which was performed by Schwartz’s Art Theatre under the title Beggars. Beggars, Charney says, misses the bigger statement and ill-prepares the audiences for the intent of the play. And of the two titles of the sequel to Golem, which title we choose to give it influences our concept of the play. If we employ The Redemption Comedy, the play is one creature, a seeming prediction of the end of days. If we employ The Golem Dreams1 we are in a space where prediction is instead wish, hope, abstraction and fantasy — the mind of a clay monster who slumbers and, indeed, never wakens in the course of the play. There is still magic (the Golem himself) but the battle between Gog and Magog, the Moshiach ben Yosef, Armilus, and the Golem’s taking the place of the Moshiach are all mere dreams.

One of the central questions from the first part of Golem is repeated (and will be repeated yet again in Miracle in the Ghetto): Can Jews take up arms? Are they allowed to fight only in self-defence? Or may they act pre-emptively? Can we be like ‘them’, or must we evade this by other means? The Golem is meant to keep Jewish hands free of blood, and the Moshiach ben David’s downfall in the second Golem play is spilling blood.

This question had clearly occurred to Leivick himself, as he helped establish self-defence groups in Russia with the Bund,2 and it will return for him again in a real-world way, when he meets with Ben Gurion in Israel in 1950 and interviews him — may, and should, Israel have an army like any other secular nation? May they attack first, or only in retribution?

There is also the question of the Moshiach — Maharam of Rothenburg, it seems, is another war-time ‘anti-Moshiach’ play — and part of a kind of artistic bridge between Golem II and Miracle in the Ghetto.

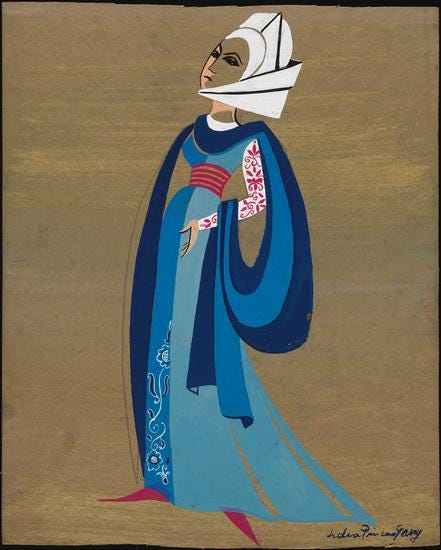

The Messenger from Eretz Yisroel, Costume design for Maharam of Rothenburg, from the Museum of the City of New York, Accession 65.83.1

In the Golem plays, the Moshiach is first driven away in favour of the Golem (Golem I) and then replaced by the Golem entirely (Golem II).

There’s still a magical element (time travel and the Eternal Jew) in Maharam, but the only Moshiach is a pretender. Daniel tells them stories of his present, their future — a whole generation of mortals who are their own Moshiach in what will become Israel. By the time we reach the Warsaw Ghetto, there is no magic and no Moshiach, only the madman’s visions of Elijah and human courage.3

And there are a few further similarities between Maharam and the Golem plays. Both, of course, feature real, historical characters: The Maharal of Prague and the Maharam and his students, Knup, the Count, etc. Lines are even specifically drawn between the Maharal and the Maharam — The Rabbi’s daughter (and desire for her) is a major plot point, the Maharam temporarily raises the paralysed Knup to stand (Knup describes his body as a ‘lump of clay’)4 and Golem’s Tadeush cannot believe the rage he sees in the Maharal and, in a similar scene, the Count mocks the anger and bitterness of the Maharam.

Jewish rage is something to which Leivick is no stranger, either, exploring it at several junctures in his work, and confessing poetically, at least once, to his own repressed, inherited, Jewish rage — his own yichus:

From ‘Clouds Behind the Forest,’ New Poems, 1932.

Esther, Costume design for Maharam of Rothenburg, from the Museum of the City of New York, Accession 65.83.5

To be continued…

As Habima, the only company to stage it that I know of, did. Leivick himself seems to use both, even in the same piece (though perhaps to avoid confusion in the reader). Here’s the synopsis from Habima’s archive: The Golem Dreams. Note: Hanna Rovina (of Dybbuk fame) played Hanina, the Moshiach Ben Dovid — in both halves. The play was published in Yiddish and in Hebrew translation.

At least one version of his arrest, Leivick is concealing weapons for the Bund.

Wedding at Foehrenwald reintroduces the Moshiach drama — but it’s a changed, hybrid beast now. The Moshiach must be convinced to be the Moshiach again by the living generation who needs him — but will continue to be their own salvation.

Geleymt — paralysed, versus clay — leym.

This is very beautiful. Perhaps you can give more reference on what are you describing. So if you come in the middle, i.e this post, it is more clear.