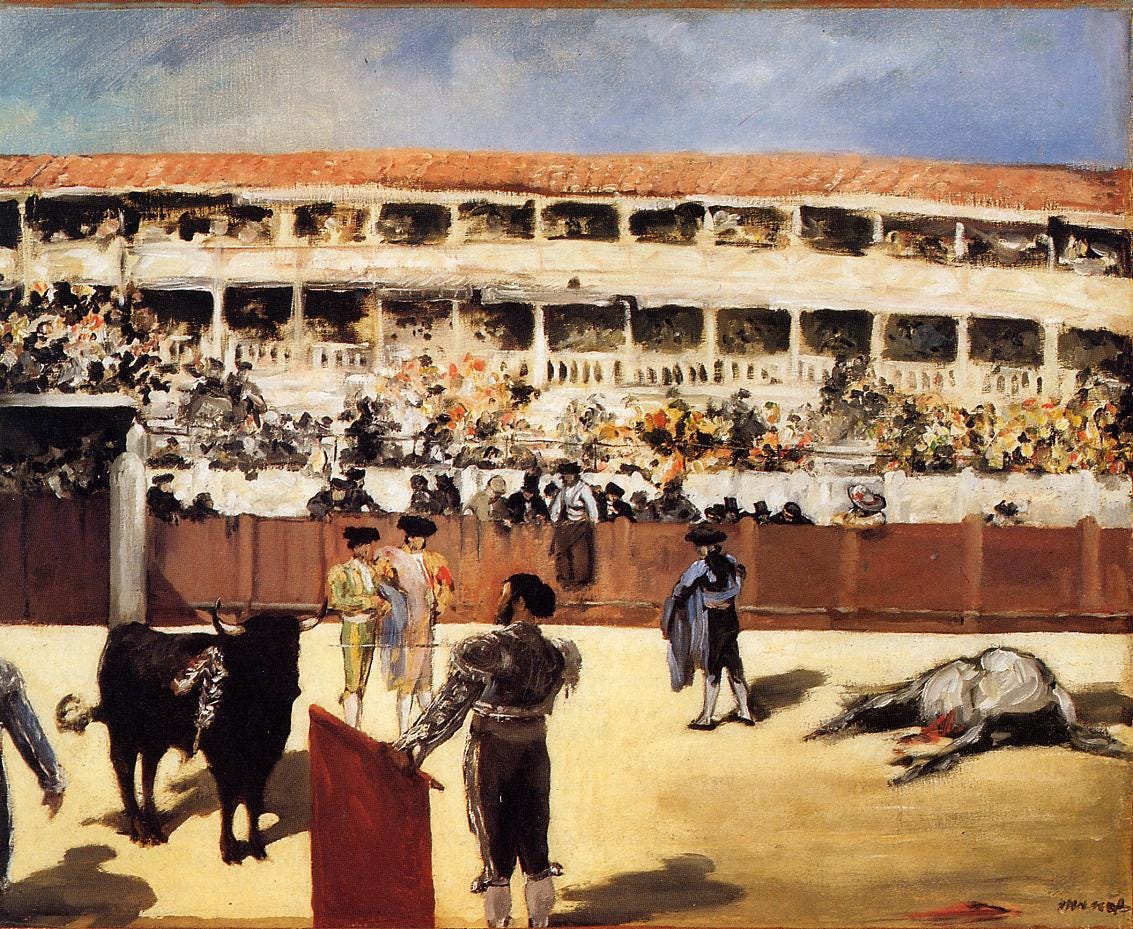

Bullfight – Death of the Bull (c. 1865) by Édouard Manet. There’s that red flag again…

Just a quick note to new friends and those of you who persevered through 14 weeks of Leivick in Israel: Thanks for being here! There isn’t really any rhyme or reason to what goes on, other than I write about/translate what I think is interesting and of value at a given time.

Previously, I wrote a bit about the poem ‘Bullfight,’

where I posited that it was connected to Leivick’s trip to Mexico in early 1943 — no huge leap of logic really necessary there.

The original version, published in Tog in 1943, was, in fact, written while Leivick was visiting Mexico in February of that year. He writes a small introduction to the theme for the newspaper reader:

In Mexico, bullfights are held every Sunday. Six bulls are led out into the arena, and with the help of a red cloth, which mysteriously incites them, they are harried to death by the toreadors. Then the toreador sticks a sharp sword into them and finishes them.

By the time it appears in 1955’s Blat oyf an eplboym (Leaf on an Apple Tree) — having been skipped over for inclusion in 1945’s In Treblinka bin ikh nit geven (I Was Not in Treblinka) where at least one of the other poems written in Mexico appears — ‘Bullfight’ has lost the lines giving its specific provenance and explanation.1

It’s also quite a different poem in many respects.

This isn’t the first time that Leivick has edited a poem between publications. There are a number of poems, both in collections and published in Tog, which are labelled ‘variant.’ I’ve already mentioned his removal of at least one small passage from ‘The Wolf’ and his deletion of lines and re-contextualising of ‘The Stable’ between 1923’s In Keynem’s Land and the Ale Verk of 1940, as well as his exclusion of some poems and rearrangement of the order of others.

I think it’s worth looking at the substantial differences between these two versions of ‘Bullfight.’

Both begin in a very similar fashion, but quickly go off in different directions. Here’s the start of ‘55 in my translation from my first visit:

Six they were —

Six brave, bewildered, bulls.

Six foolish bulls,

And perhaps not foolish at all.

For in truth —

How were they to know

What an arena means

And a crowd of forty thousand?

What they mean and what mean

Toreadors,

And riders,

And spears,

And swords,

And treacherous cloths?

(1955)

And here’s ‘43:

Six they were —

Six black, bewildered, brave bulls,

Six foolish bulls.

And perhaps not foolish at all.

How were they to know

What an arena means

And a crowd of forty thousand?

What they mean and what mean

Toreadors,

And riders,

And spears,

And swords,

And — red cloths?

(1943)What is immediately different between the two is the heightened colour imagery in the 1943 ‘original’; black bulls, red cloths. The earlier version also continues here, unbroken, while the later breaks for a second stanza.

Even a man would be no wiser

If held for days in the darkness,

And then chased out into the arena

Flooded with flaming tropical sun

And attacked with darts and picks

And eyes maddened with red,

And the crowd cheers, laughs, roars, gasps —

What would he do, the man?

Truth be told,

What would remain for him to do,

If not to leap about as though on scalding coals,

If not to turn round and round

And strike his forehead against all the fences,

Into his own dizzying shadow,

And — into the the red cloth?

(1943)The sun is not just flaming, but tropical. And rather than the man’s own delusion — there’s the red cloth again.

The stripping of the specificity of the introduction and the ‘tropical’ sun in the 1955 version certainly works, together with Leivick’s placement of the poem amongst those for the lost Jewish Soviet poets, in dislocating it, and recontextualising the poem to other, more far flung events and circumstances — his own imprisonment, that of the poets murdered by Stalin in 1952. We still have the blinding sun, but no longer have the heat which dulls the senses of the onlookers, making them indifferent to life, as Leivick writes in his articles about Mexico, and death. Something else makes them traitors.

Following this, though, we have a more obvious divergence. 1955’s ‘Bullfight’ keeps the focus solely on the bulls. We get a bit of their inner life. The futility of that life.

Oh, six unhappy bulls,

Six foolish, fooled, bulls;

Your dream,

Your luck,

Your fiery, flaming yearning —

Your death.

Six poor, condemned bulls,

My heart is with you

And not with crowd and toreador.

But what comes of it?

In truth —

What comes of it

Is that the dream is full of mockery

For you and your useless horns.

(1955)But in 1943, we stay with that red cloth, which occupies a sizeable place in the imagery of that version. And we get a possible interpretation of what that red cloth might mean — both to the bulls and in the wider context of the poem itself.

The red cloth, the red cloth,

Oh, the red cloth — your dream

Unhappy, deceived, six bulls —

The red cloth — Your luck,

Your fate,

Your desire,

Your fiery longing,

Your God —

Who is and isn’t there,

Who mesmerises and isn’t there, —

The red cloth, the red cloth,

Your death,

Poor, maddened, condemned six bulls. —

(1943)

The red cloth (here repeated, as Leivick often does, in what Charney called his ‘internal refrain’)2 is desire, longing, luck, fate and — God. But one that is absent, or which never was there. An interesting proposition to consider in the war years. A belief that is used to lead, incite and then snatched away to reveal — the toreador with his picks and swords. And whether or not this is a god with a large or small G, it’s doesn’t quite harmonise with the God we see in parts of I Was Not in Treblinka (mute, wounded, suffering) or, indeed, with the God we see in Leaf on an Apple Tree (there, but the relationship needing renewed, reignited, to restore both Man and God). Is it perhaps one of the defunct Aztec gods that Leivick writes about in his other Mexican poems and articles? The statues there, the gods themselves gone?

1943’s stanza continues, running together what will become two separate stanzas in 1955. The red cloth appears again, in place of 1955’s ‘dream’ and is also not only full of mockery, but ‘betrayal.’ Whatever god this is, embodied in that red cloth, it cannot be replied upon. It is the traitor, not the crowd. 3

My heart is with you

And not with crowd and toreador.

But what comes of it?

In truth —

What comes of it

Is that the bit of red cloth is full of mockery,

Is full of betrayal,

For you and your useless horns.

The sword pierces your spine

The picks deep in your entrails

And the crowd roars

And the toreador is jubilant,

And you, one after another,

You fall, you fall, you fall.

(1943)The close of the 1955 version unpicks all the images, mirroring the first stanza of that version of the poem. The dead bulls are dragged away, the toreador and sword have served their purpose and are now useless, the crowd has almost ceased to be a crowd, exhausted and also having fulfilled their role and the sun, too, sets, dragged down and away.

Six they were —

Six brave, bewildered, bulls.

Charging, foaming, bleeding —

And now they are dragged with a chain by the feet

Down from the arena,

And their horns, useless, drag behind;

And the sharp sword dangles

Extinguished in the hand of the toreador,

And the crowd sits, roared to exhaustion,

Crumpled like a traitor — the truth.

And the sun, too, extinguishes behind the arena,

And the sun, too, is dragged with a chain

Down from the heavens,

Down from the heavens,

Down, down.

(1955)The closing stanza of the 1943 version is a different beast altogether. Rather than a sword hanging ‘extinguished’ in the hand of the toreador, it’s the real weapon, the thing that actually killed the bulls — that red cloth again; Their god, their betrayer.

Six they were —

Six black, bewildered, brave bulls.

Six they fought in mocking struggle

Chasing, foaming, bleeding —

After the traitor — the cloth,

And perished,

And now they are dragged with a chain by the feet

Down from the arena,

And their useless horns drag behind them.

And the traitor — the cloth

Hangs like a rag, rumpled and extinguished

In the dangling hand of the toreador.

For in truth —

What worth does the red cloth have now

When all six are dead? —

In truth —

What worth does it have now

In the toreador’s dangling hand?

(1943)Here, I think, Leivick does connect this cloth, at least in part, with the ruins of the Aztec civilisation he’s been seeing, with the images of their gods and idols, as well as with his own conception of Judaism. Because, he asks at the end, what worth do gods have when all their followers are dead? Does a god not die where there is no one left to worship them? You can then tie this back into the notions of the perpetuity of the people of Israel — there will always be a living God because there will always be Jews to worship and there will always be Jews to worship because there will always be a living God.

The red cloth — you’re tempted to read it as the red flag. Particularly if you know that later version, couched in those poems about Markish, Bergelson, Kulbak,4 the poems about the new red flag hanging over the doors and flying from the ramparts of the old prisons. Especially if you read Leivick’s casting of Stalin (and other Soviet leaders) as false gods and idols of stone. Not so far away from the stone snake gods of Mexico.

And you can certainly give in to that temptation. Because that’s exactly what it is: The red flag.

Leivick threatens, in interview with A. Tabachnick, to produce a book of biographies of his poems rather than any complete autobiography. Obviously, not a book he ever got to write formally. But he often does as much in the pages of Tog when you read the articles surrounding a particular poem, a thing wonderfully possible in today’s world of digitisation. An otherwise obscure poem is suddenly explained by reading a week back or ahead.

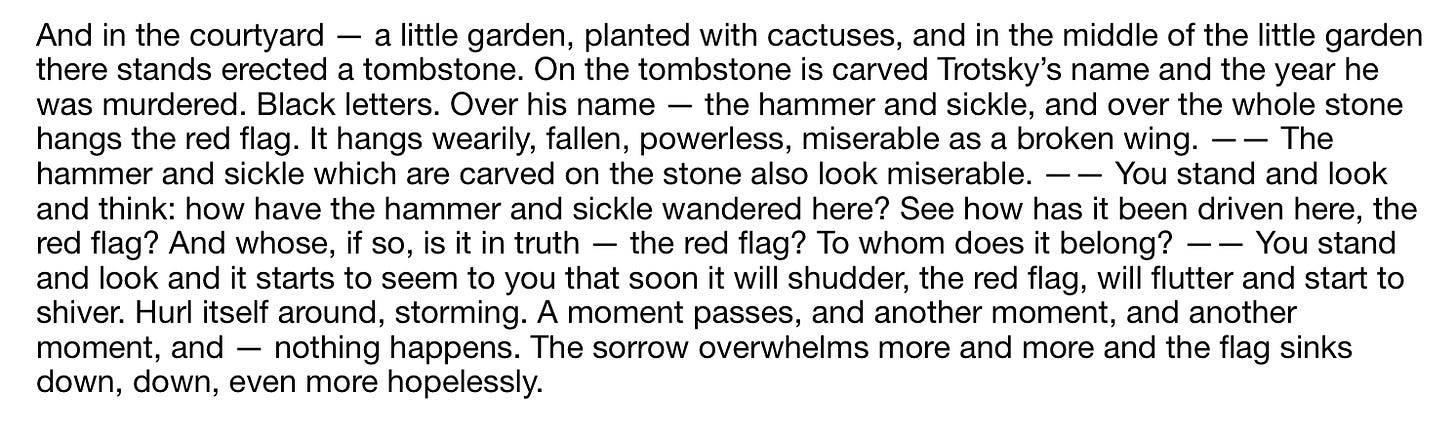

Leivick himself, in fact, explains how ‘Bullfight’ ultimately makes it into a block of poems about Soviet Russia: It’s where the poem, in a sense, always belonged. While he’s in Mexico City, Leivick goes to visit the house where Trotsky was murdered and sees his grave in the house’s garden — and this visit and description of the grave in the articles for Tog, at roughly the same time the poem is published, join up those dots.5

There’s that rag-like red cloth. Who is/was the bull?

The 1955 version is precisely where we mostly lose the red cloth/flag, its treachery and the deceitful god it embodies. It’s almost entirely stripped away. Why? Perhaps the mob and who they crown — their toreador of the hour — is more important. Perhaps it’s too much, even for a more-is-more kind of poet and the power lies in the red flag’s near textual absence; there is a brief mention of it and of red, but nothing on the scale of the earlier version. Its placement, just as the surrounding articles in Tog once did, gives it a frame of reference, context.

By merit of the poem’s placement, we know very well what colour the cloth/flag has to be. 6

Photo by Gunther Schenk.

Here’s the 1943 version in full, in my translation:

Bullfight

In Mexico, bullfights are held every Sunday. Six bulls are led out into the arena, and with the help of a red cloth, which mysteriously incites them, they are harried to death by the toreadors. Then the toreador sticks a sharp sword into them and finishes them.

Six they were — Six black, bewildered, brave bulls, Six foolish bulls. And perhaps not foolish at all. How were they to know What an arena means And a crowd of forty thousand? What they mean and what mean Toreadors, And riders, And spears, And swords, And — red cloths? Even a man would be no wiser If held for days in the darkness, And then chased out into the arena Flooded with flaming tropical sun And attacked with darts and picks And eyes maddened with red, And the crowd cheers, laughs, roars, gasps — What would he do, the man? Truth be told, What would remain for him to do, If not to leap about as though on scalding coals, If not to turn round and round And strike his forehead against all the fences, Into his own dizzying shadow, And — into the the red cloth? The red cloth, the red cloth, Oh, the red cloth — your dream Unhappy, deceived, six bulls — The red cloth — Your luck, Your fate, Your desire, Your fiery longing, Your God — Who is and isn’t there, Who mesmerises and isn’t there, — The red cloth, the red cloth, Your death, Poor, maddened, condemned six bulls. — My heart is with you And not with crowd and toreador. But what comes of it? In truth — What comes of it Is that the but of red cloth is full of mockery, Is full of betrayal, For you and your useless horns. Six they were — Six black, bewildered, brave bulls. Six they fought in mocking struggle Chasing, foaming, bleeding — After the traitor — the cloth, And perished, And now they are dragged with a chain by the feet Down from the arena, And their useless horns drag behind them. And the traitor — the cloth Hangs like a rag, rumpled and extinguished In the dangling hand of the toreador. For in truth — What worth does the red cloth have now When all six are dead? — In truth — What worth does it have now In the toreador’s dangling hand? Mexico, February, 1943

This, in and of itself, isn’t unusual. In compiling a list of articles and poems in Tog, I’ve found there are several poems which have a line or two of explanation — on at least one occasion, a correction of a misprint in a previously published poem.

What it reminds me of most is ‘The Stable’ — the titular shul turned stable the central image, just as the red cloth is centred here. The refrain of ‘The stable, the stable’ in particular.

Very much not the God of Leaf on an Apple Tree, who, in one poem, has carried the speaker through something unnamed — but which can be supposed to have been the horrors of the Second World War based on where in the collection it falls and Leivick’s own note about the organisation of the volume. There are a couple poems composed earlier, but left for the later volume. Why all of them were retained, I can only guess at this point.

In 1955 they don’t quite know yet what’s happened. They’ll only find out in 1956. And, well, that’s where I’m heading next.

While the poem recasts it as ‘sport,’ the article likens it all to a children’s game. Well, a children’s game of coup, attempted, and then actual, murder. There, the red flag is a torn shirt.

It’s tempting to draw a line here to Leivick’s drama Hirsh Lekert and the lost revolutionary red flag which is replaced by another sort — flowing blood. I should also mention that at least one other bloody-flag marches though the poems of Blat oyf an eplboym, and that’s Leivick’s own Simchas Torah flag, which marches all the way from Ihumen to Israel.