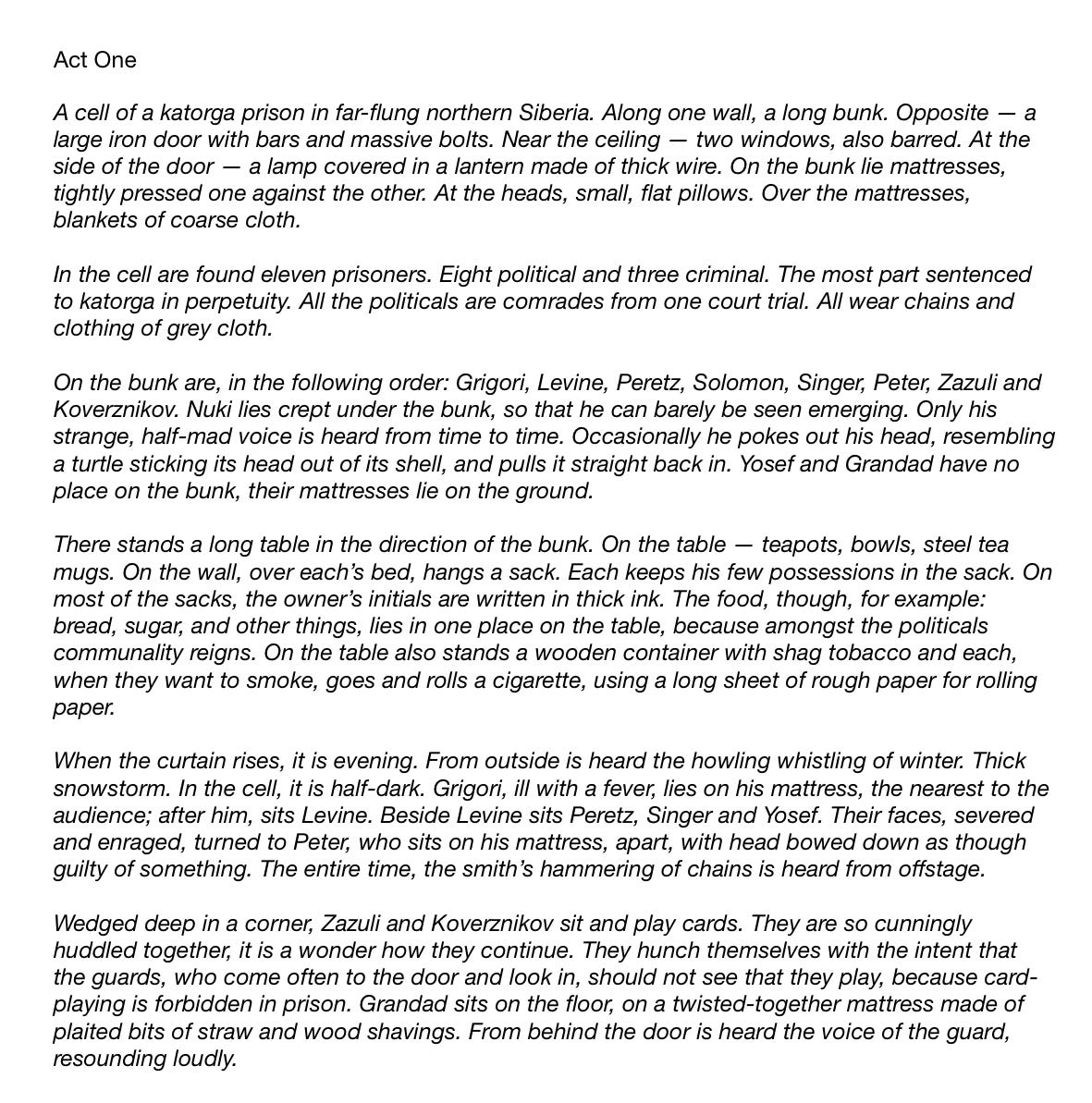

A rather well-known picture of Leivick from 1910 in Butyrka Prison, Moscow — here from Shmuel Charney’s H. Leivick: 1888-1948. The prisoners slept in them and, he writes in Oyf Tsarisher Katorga, the trousers fastened up the side with buttons to accommodate the rings fixed around their ankles.

1922’s Chains, as one might expect, is largely hung on the incidents Leivick also mentions in Oyf Tsarisher Katorge

and at least one not there, but mentioned in interview with Y. Pat. One of the fragmentary plays at Yivo also touches on prison.

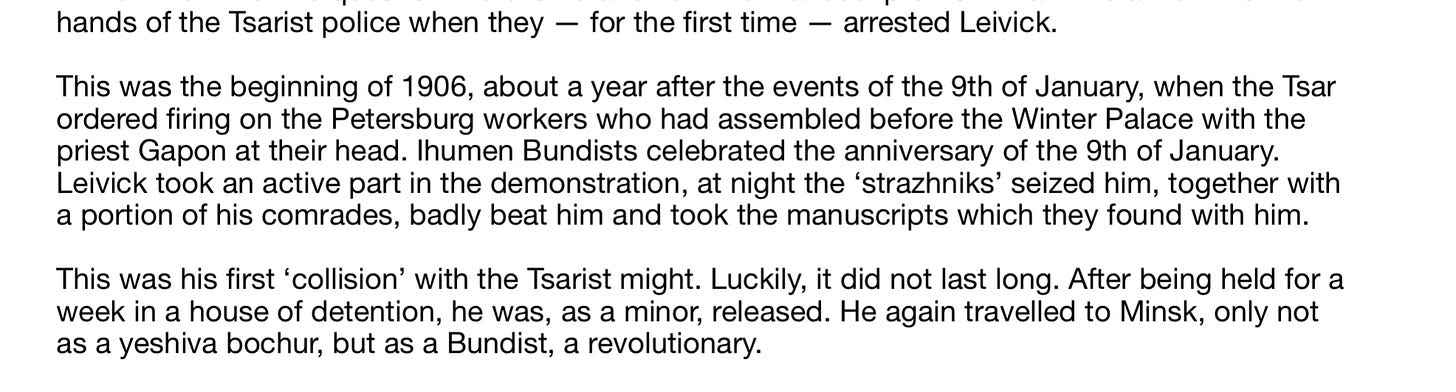

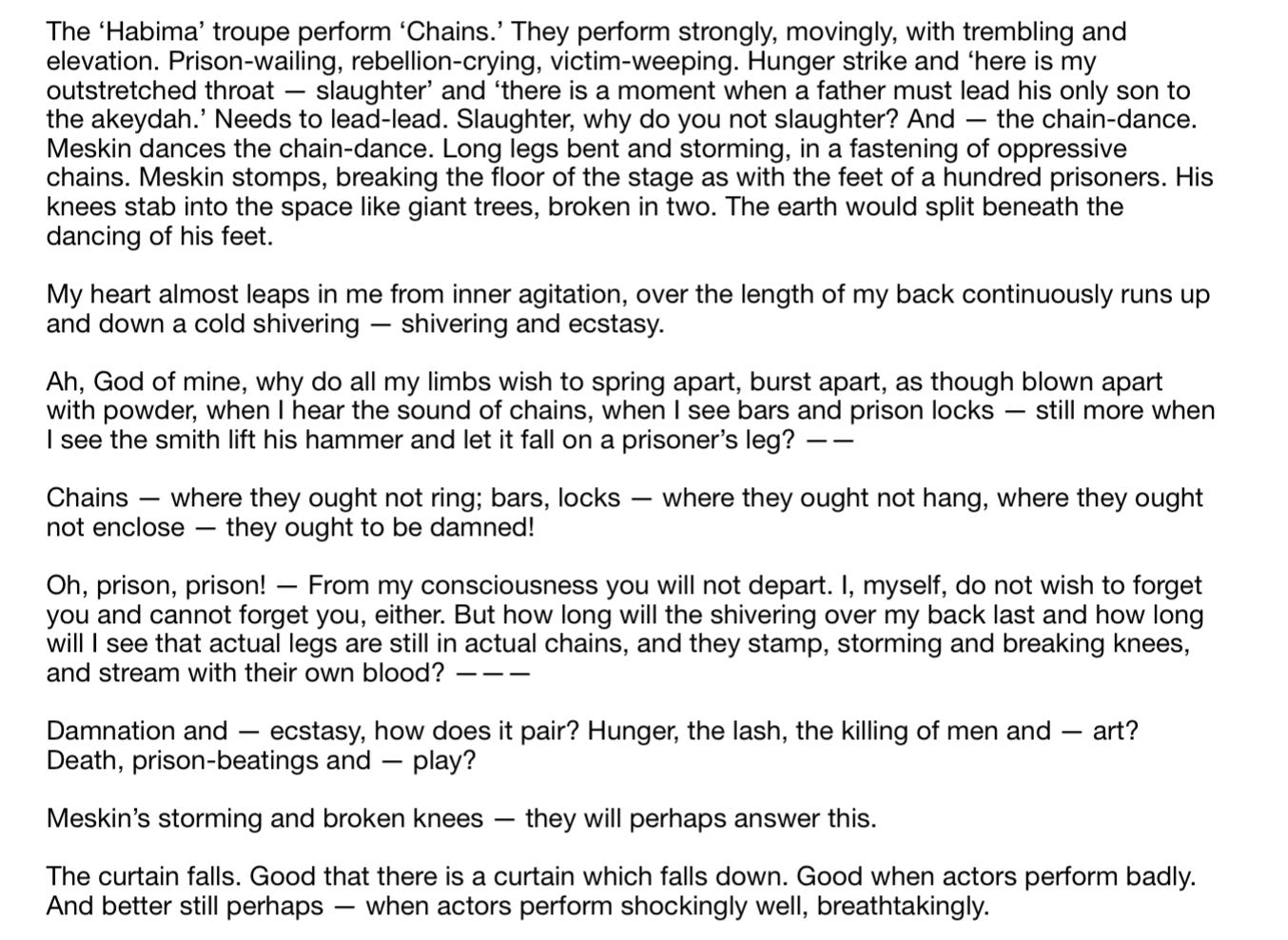

Father Gapon at Petersburg.

Leivick’s first arrest, at sixteen, was for the Bundist protests on the anniversary of ‘Bloody Sunday,’ January 9th, when Tsarist troops fired on Father Gapon and his followers, killing many. I suspect his friend/roommate at the time inspired the name Daniel in play.1 According to both his interview with Y. Pat and Shmuel Charney, he was beaten all night and released. And promptly went back out to do it all again.

From Shmuel Charney, H. Leivick: 1888-1948.

From Yankev Pat, Conversations with Yiddish Writers.

Chains was written right about the time that Leivick, along with a group of other writers, quit the Morgn-Freyheyt over their toeing the (Communist) party line over the Hebron massacre in 1929, the first of two major breaks by Leivick with the Soviet Union. The second would come with the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact in 1939.

Conversations with Yiddish Writers.

Apart from these details of an attempted escape in the interview with Pat (an escape attempt and its aftermath drives the first two acts) and Charney’s noting that Leivick went on hunger strike in prison (the business of the play’s second act) the play is so heavily reliant on episodes from his experiences detailed in In Tsarist Katorga2 that I’d basically have to quote the whole book: socialists who cannot uphold their ideals in prison, whippings, a prison riot in which Leivick participated, battering the cell door with the table.

From H. Leivick, Chains, 1931.

The cell, of course, is described largely as he describes his own — with one notable omission: the crucifix. The crucifix comes into play in a major way in both In Tsarist Katorga and at least one poem from 1919’s Lider, ‘Jesus.’ Jesus, however, makes no dramatic appearance in either statue (both) or hallucinatory (Tsarist Katorga) form. What there is, which perhaps reads a little strangely in light of the conflict with Christianity in his other works about the experience, is a likening by one of Leivick’s typical mad, perhaps prophetic, characters, Nuki, of bread to body and blood.

I don’t think I’m too far into this imagery, these proclamations, as being reminiscent for Christian thought, as well. The other works prove that there is a contact with Christianity, for better or for worse,3 tangled into that experience.

Leivick went to see the second act of. Chains performed in Tel Aviv in 1937 in Hebrew by Habima,4 and writes of the rather unnerving thrill of seeing it acted out on stage. What strikes him most, he writes for Der Tog, is the ‘Chain Dance.’

From Der Tog, 12 December, 1937.

What is the Chain Dance?

In some ways, it’s the anti-Mayofes5 dance — it’s not, in its two real-world appearances in In Tsarist Katorga, purely for humiliation and degradation, or for appeasement. There, the dance is performed once by one of Leivick’s fellow revolutionaries, once by one of the criminals.

In the first of those instances, it seems to be a rather spontaneous act of defiance and anger and less of a dance — taking the expected sound of each of their chains —Leivick says they weighed about eight pounds and were fastened by a thick leather belt around the waist while one was awake — and spinning it out into a transgressive act of reproach for not sharing food amongst the cell ‘commune’ (this is included in Chains, in a fashion,6 but without the accompanying dance):

From In Tsarist Katorga, 1959.

The second incident in In Tsarist Katorga is when it is performed in full by one of the criminal prisoners, Kolodnik. His dance isn’t Karlov’s pure anger and rather disorganised rattling but is a rather more choreographed affair, part demand, part entertainment, part protest.:

From In Tsarist Katorga.

The Chain Dance, as it appears in Chains, is a slightly different creature. Rather than summoning the benevolent guard who gives the cell a privilege which has been taken away in punishment, it is demanded of the criminal prisoner Zazuli by the spiteful, ultimately murderous prison warden, Druzhinin, as a demeaning performance — far closer to the Mayofes dance. Levine, the de-facto head of the political prisoners, forbids him to do. It’s perhaps significant that it’s never the Jewish revolutionary performing it for the gentile guard in real life or on stage. And, in fact, refusing to let it be done.

That’s not to say there isn’t an element of rebellion in the play’s dance, even in light of this. It’s still defiant.

While Druzhinin and, in fact, Levine read this only as humiliation, the dance in the closest we get to a glimpse into Zazuli’s own inner life — his own struggle. No small thing in a social drama concerned with the fates and elevations of all mankind.

And what does Leivick have to say about dancing himself? That he doesn’t.

He can’t bring himself to join the famous horas at Ein Harod in 1937. He can’t do it at Landsberg either, in 1946, instead sitting and chatting with Zivia Lubetkin. He does, however, get pulled into the dancing at a kibbutz near Foehrenwald DP camp — the dance, we find from Israel Efros and Emma Schaver, is a ‘Shoshana’ where one partner leaves and a new partner is pulled in. Leivick is finally pulled in, and when it is his turn to chose a partner, he dances with a child:

Emma Schaver, We Are Here!, 1948.

(A note: Like everything I’ve read [Tsarist Katorga, Who’s Who, With the Surviving Remnant, etc] I typed as I went, so I’ve got full rough English, from which I’m quoting as usual. And I don’t particularly have a rhyme or reason how I’m working my way through Leivick. It’s a case of what strikes me on a given day. It is a diary, after all, not a thesis.)

Perhaps, also, the Daniel of the Tanakh. After all, he does seem to enter into a very dangerous sort of den…

Also, Leivick’s own repeated themes, such as the Akeydah. Levine tells us there is a time when one leads their own son to the Akeydah and a time when one cannot even sacrifice a match. Later, having become the new warden, word finally becomes deed and he ‘sacrifices’ a match to light the cell lamp — will he then be able to sacrifice his ‘son,’ Daniel? That’s the crux of the third act. Subtly underscored and beautiful.

Three of his cellmates described in In Tsarist Katorga appear to be practicing(ish) Christians; One viewed fairly neutrally (Grandad’s ‘original’), a Tolstoyan Christian whom he rather likes (Rudin) and to whom the character of Daniel in Chains owes quite a bit, and the last, a man who murdered a Jewish family with an axe (Bassanov, who doesn’t have a corresponding character in the play. Incidentally, Leivick tells a slightly different version of Bassanov’s story in the Morgn-Frayhayt, giving what might be his real name.)

He also writes at some length about his feelings seeing his name altered for Hebrew into ליויק, and about the scuffle which follows the director of Habima, Chemerinsky, finishing his speech on the stage welcoming Leivick in Yiddish — a privilege allowed to a visiting artist, as Leivick was, but not locals. Here’s a clip of a later production in Hebrew by Habima.

A sort of Jewish version of ‘shucking and jiving’ — a forced parody of prayer and shuckling. A ‘Mayofes Jew’ being not entirely dissimilar to an ‘Uncle Tom.’ It features in a few places, including derisive comments about Jewish music and musicians and as a plot point in novels by I.J. Singer and Itzik Manger.

The ‘selfishness’ regarding food as a basic right is visited repeatedly in Chains, underscoring the hypocrisy of the shunning of Solomon for the ‘infraction’ of not sharing.