The Hebrew Standard, 6 October 1922

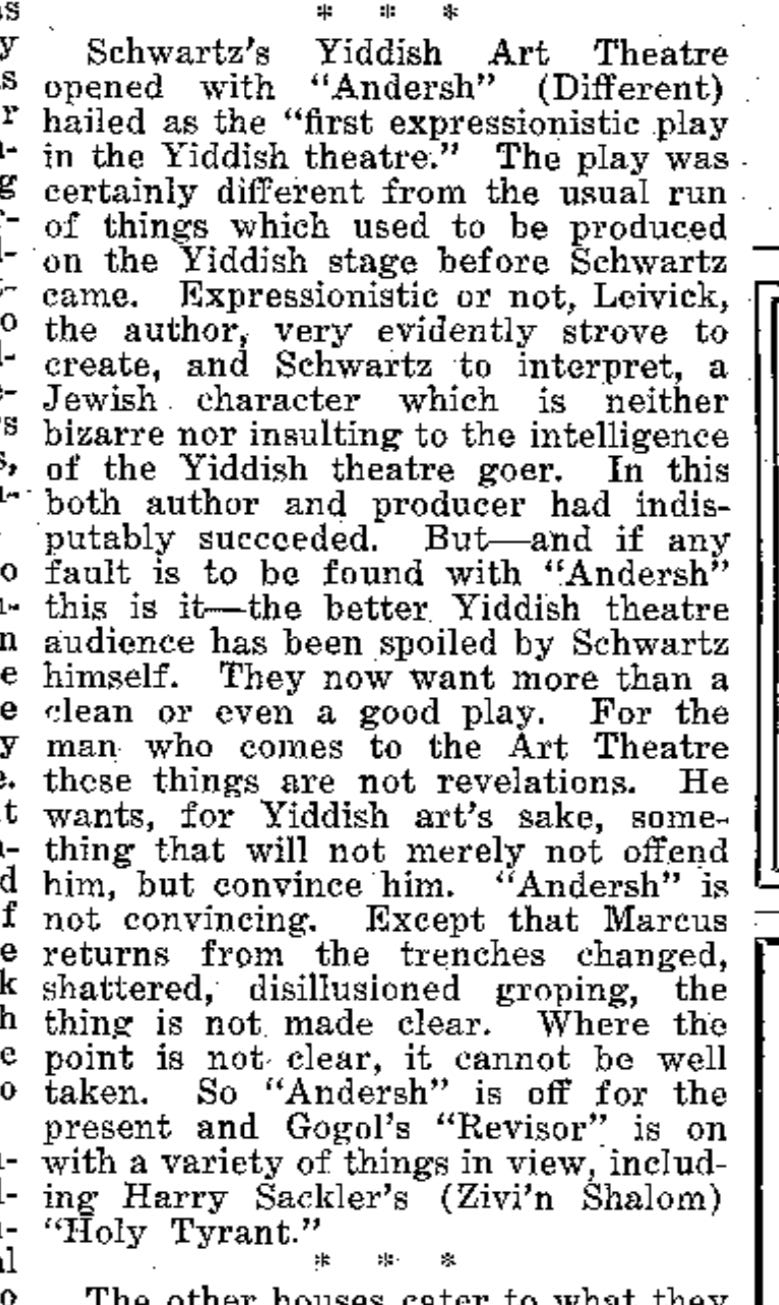

I think the absolutely dreadful reviews of 1922’s Different (even in English) have a point…that it is very much directly stating authorial philosophies. Which doesn’t really make for great drama or naturalistic dialogue. Which is probably what Schwartz’s audience was expecting in the wake of Rags.

But the play isn’t really a naturalistic one, though it wears that mask a bit, and philosophies and opinions are pretty valid ones by this juncture: there’s just not a truly advanced language of psychoanalysis and psychology yet, to talk about what happened to people in the war, in pogroms, immigration, illness, etcetera, in 1922. Officially, PTSD and most of the language around it are decades away.

So the problem of the play (at least in part) is the search for a language to express difference and trauma. The words that he wants, needs, aren’t really there. The problem with the play is that the language to express it doesn’t really exist yet in Leivick, either. We are told Marcus is ‘shocked’ upon his return from the First World War. Which is about the sum of it. ‘Different,’ he keeps repeating, as the only word he possesses in his vocabulary to describe how things are now.1

From S. Charney, H. Leivick: 1888-1948.

We see that the veterans who are now physically handicapped are at least getting half a hero’s welcome. They’re physically altered, their wounds obvious.

Marcus and his equally altered by the war comrade, Isidore,2 who seem (to me, anyhow) to have hospitalised with a mental breakdown beyond any physical injuries they had, got nothing and get nothing. Why can’t they just slip back into their unchanged apartments and their lives which were put on pause — are they such different men now?

Are they still men at all?

Leivick is acknowledging these psychic wounds. Or trying to, anyway, if a bit awkwardly. He knows, from personal experience, that it’s difficult to live in a ‘fragmented’ sort of way, with one foot in one world and the other in another: Bochur or Bundist, Poet or Wallpaper-hanger, Sick or Well, Jew or Assimilated American. He knows that to live in the wake of life-altering experiences is a struggle; prison, serious illness, immigration, they’ve all left their mark on the author.

Marcus, the creation, finds the situation untenable. There is no compromise. No wholeness. And, rather importantly, Leivick doesn’t necessarily think Marcus is wrong. If we follow Leivick’s definition of Akeydah as a passing through death entwined with chosenness, as in the late play In the Days of Job, then Marcus has endured his Akeydah and come out the other side marked. Both less and more than he was. Touched by, perhaps, the divine.

Even more than Marcus’s altered Jewish manhood, there is Isidore’s. He tells us that he was once, back home, a Yeshiva student himself — perhaps destined for a esteemed place in the culture that he was once part of, which once existed for him (and for Leivick himself). No longer Itzik bar R’ Shaul HaCohen, melamed, he is now only Isidore Cohen, traumatised war veteran.3

From H. Leivick, ‘Different,’ Unpublished Dramas, 1973, as are all extracts which follow. Words in italics, barring stage directions) denote phonetic English or other languages for my own sanity and reference.

Isidore is a step too far to be Leivick’s hero, and as such must remain of one of his half-mad truther-tellers, but there’s sympathy and explanation for him, too, as well as room for his trouble — which is also a step beyond Marcus’s. While Marcus’s father has died, his mother has safely come to New York. The family Isidore left at home in the Old Home has been tortured and slaughtered in what seems to be the Petliura pogroms.4

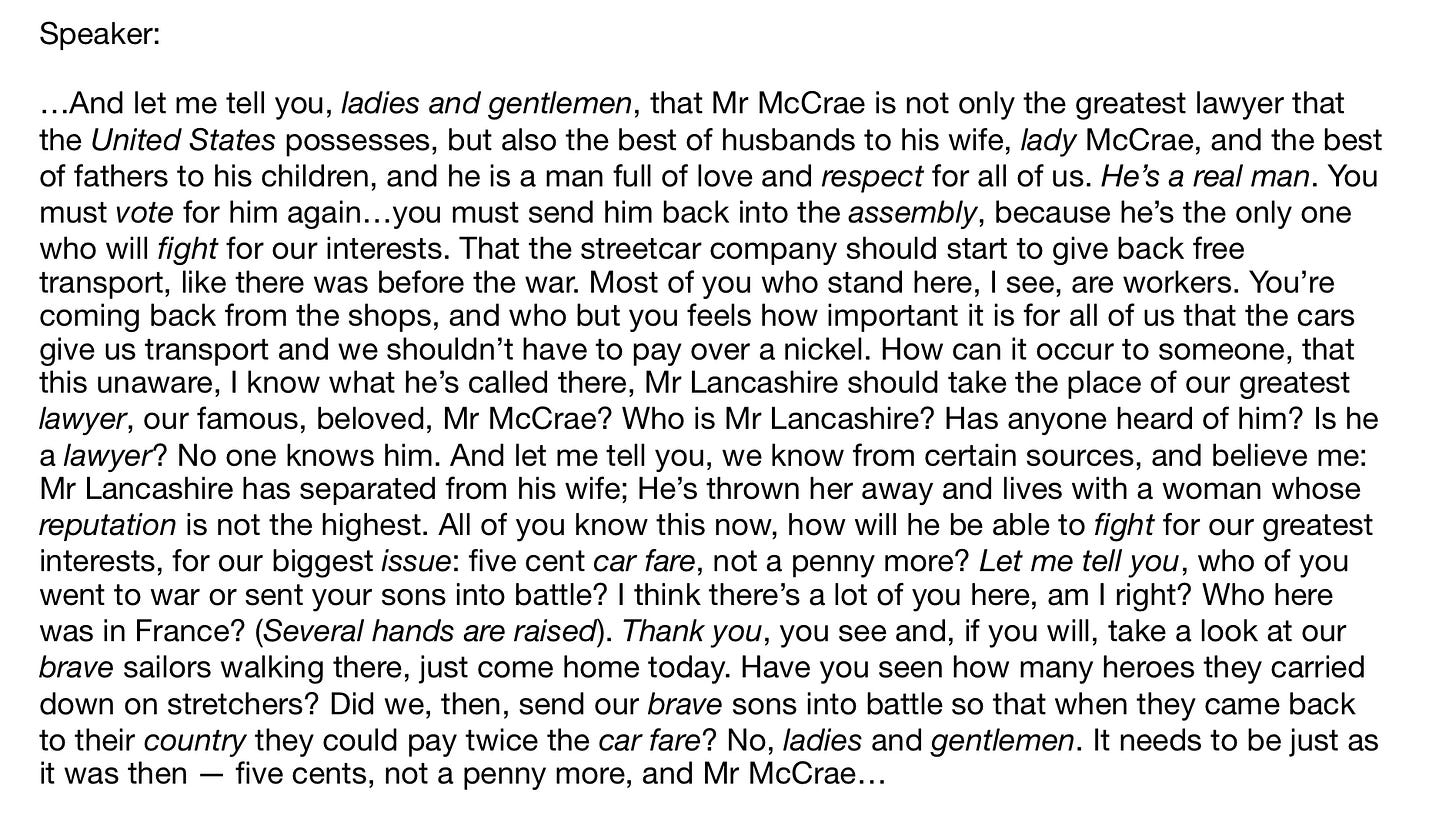

The concept of masculinity is addressed directly in the play, notably by the police captain who has arrested Marcus for interrupting a political meeting — he celebrates ‘our boys,’ a group from which Marcus is being very decidedly excluded on a number of counts.

War wasn’t a game or a dance to Marcus or Isidore and they didn’t come back as though it had been.5

Specifically, there’s a concept of an American masculinity being explored (however roughly) in the Captain’s lines — it was a ‘baseball game’ — a concept from which an immigrant Jew from Russia is excluded, even if he’s now Marcus and not Mottele. He doesn’t know how to play this American game, not baseball, not war, as even male American children do (‘boys’). Jewish immigrant masculinity might as well not be.

Marcus is questioned about being a socialist, a Bolshevik, and threatened with deportation. The physically and mentally ‘weak,’ the anti-capitalist and the sick — particularly the immigrant — are not real Americans. Not men.

Furthermore, to drive this home, Leivick puts the idea of Marcus’s wife undressing before him, of his touching her in a sexual manner entirely off the table. 6

He isn’t a man in this respect, either and cannot perform as one — Bertha has longed and presses herself to him. He rejects it. The human body has been too completely conflated with violence for there to be any further relationship between it and desire.

Leivick’s Abelard, coming about a decade later, is horrified by his parents having sex and, of course, there is his later castration. Here we’ve got it all symbolically. The most ostensibly male thing that Marcus could have done by the societal norms in which he lives — going to war — has left him, according to these same standards, not a man.

Because I love Joyce, and because this is 1922, I feel compelled to note that Marcus is sharing the same air, in a sense, with Leopold Bloom in Ulysses, the ‘new, womanly man,’ another Jew of dubious masculinity.7

Leivick had also begun treatment for TB by this juncture in New York, spending, by his own account, 1920-1922 in the mountains. Some of this may well be personal sentiment about being unwell and unable to earn a truly secure living in a physical trade. Being unmanned, in a sense, by illness.

This idea of masculinity pops up in relation to his own life and trade overtly in his poetry, where even his son admonishes him to ‘be a man’ when he is momentarily defeated by the inability to find work.8

Despite having fought for America, Marcus is still Not an American, Not a Man — not contrasted to the ‘real man’ political candidate who loves his wife (Marcus will not touch his), is the greatest of fathers to his children (Marcus is not a father). Even the opposition candidate has left his wife for another woman — dishonourable, but still stereotypically masculine.

To be honest, Marcus isn’t very good at being a certain type of Jewish-American man, either, one who, while not exactly macho, has a comfortable, stereotypical, middle-class existence as a shopkeeper, son, husband and father.

Two, three times an ‘Other.’

And Marcus welcomes all of this — he is an enemy. But not only to America — to society as it stands. He’ll wear his own uniform. He belongs to no one as husband or son any longer. His (and Isidore’s) stock which grew greater was — the lice which fed on his blood, not his business partner’s goods. His comrades are the rest of the ‘others’ who didn’t make it home either in whole or in part.

You’ll have to pardon my going on about masculinity, being only an observer on that count. But I think it’s actually a big theme in Leivick. I’m not saying he’s enlightened, necessarily, in relation to gender, but he is often concerned with non-romantic affection and its display between men and male emotional lives.9 Marcus and Isidore embrace and kiss as a mark of their affection for each other, though Marcus turns down the kisses of the other sailors. A shade too intimate, perhaps.

While I doubt that Different is truly the first Expressionist Yiddish play, it is far more interesting and correct to consider it this way, than accept the half-hearted mask of naturalism or realism it wears in places. (Certainly both this and Shop remind me of Treadwell’s Machinal).

‘Feeling too much’ is maybe what the rest of the world thinks Leivick’s heroes suffer from — but Leivick puts the onus for that on a world which doesn’t have room for deep feeling and compels people to hide or subvert it, wearing masks or telling jokes. And you can see the author himself in this, too. Shmuel Charney comments on Leivick’s own mask which he wears in his work — a twin, a separate self, an invented protective double.

What remains after Leivick has balled up and thrown away or, at least, pushed aside all the more conventional brands of masculinity, old world and new, the bochur, the Bolshevik and the shopkeeper, the husband and son, the politician and the police, the baseball player and the soldier? I don’t think he rightly knows himself. There is only the sense that something, a Wolf or Golem or a Marcus, something different, has been created here on the shvel of the twentieth century. That room must be made for it, too.

This miniature stage world, the world with no place in it for Marcus, ends in fire. A stark contrast to all the ice that filled Leivick’s Lider in 1919. A vision of all the fire that was and is yet to come. And a lead in to Colorado, that liminal place between life and death that has both fire and snow.

The end of Different is so distinctly odd…it could almost be hallucinated. It’s certainly slightly hallucinatory. Is the ship that has been constantly mentioned, on which the deeply traumatised Isidore says he is leaving in the morning — the Glory — real? Or is it metaphorical, evidenced by its mythologised status, Marcus’s affirmation that he will join them as the store keeper aboard and Isidore’s horror at the idea? Is it an entirely different sort of glory he’s going on to?

Honestly, I think the play itself could work now if you started more naturalistically and gradually spun it into something more and more abstract. I tend to think about Leivick holistically, and I really see it as building gradually into a something really weird…but again, entirely logically so, as part of his larger corpus. But you’d have to rework it to be less clunky. Charney’s got a point — Marcus is ‘different’ enough without his constantly telling us he is.

Marcus is a man who has had some kind of awakening as a Leivickian hero (or, conversely, has been driven mad and thus achieved a different sort of clarity) and if you build the end into a quasi-religious ceremony of fraternal love and burnt-offering — the dry goods store, emblematic of capitalism, self-satisfaction and society is on the altar. Perhaps Marcus’s own life.

And I think that fits pretty well into Leivick’s larger symbology.

I won’t call what Marcus has an epiphany, because that’s the wrong language entirely and carries other religious baggage. But to use Leivick’s own language, it’s a kind of an untangling of that line — as expounded upon in The Poet Went Blind — which used to be straight and should be again, which leads from Man to God and lifts the former up toward the latter.

And then Leivick rewrites the play into Bankrupt (Bankrot) in 1927.

Shmuel Charney does point out a similar repetition of ‘rags’ in Leivick’s previous play (by contrast, a great success) Rags. This repetition occurs in Leivick’s poetry, too, where Charney terms it an ‘internal refrain.’ A device perhaps better suited to poetry or, at least, better not tried dramatically twice in a row.

Isidore Cohen was played by ‘Muni’ Weisenfreund — better known as the Oscar and Tony winner Paul Muni. There’s what seems to be a gentle poke at that in Who’s Who, also staged by Schwartz’s Art Theatre, with two characters engaged in reading what is clearly Pearl S. Buck’s The Good Earth, the film version of which Muni had recently starred in.

I am compelled to note that ‘Saul the Cohen’ shares a name with Leivick’s own father. If Leivick is Marcus in some respect, he’s signposting (I think) a certain affinity with Isidore, too.

Here the language and description of the pogrom echoes part of Leivick’s own long poem, ‘The Stable.’

War and the idea of being in the military, being forced to fight for a country that has nothing but distain for you is a bit of a minor theme in Leivick. We learn in the first scene that Marcus fled Russia to avoid being drafted there — only to be drafted in America. Leivick revisits that particular paradox more personally a little over a decade later in ‘Be Ready, Daniel, for War’ and elsewhere recounts how he was employed to keep the son of the house where he boarded up all night to help him fail his physical for the Russian draft.

One can be tempted to read Leivick’s own description of seeing whipped bodies in prison into Marcus’s horror here at violence done to the human body. Which is an interesting proposition. But it’s worthwhile to tread carefully, in light of Leivick’s own statements that he doesn’t put himself on the page unfiltered.

Joyce’s vision is a little troubling to me in that coming from a non-Jewish author it retains a certain closeness to the antisemitic trope of the effeminate Jewish man rather than a fuller exploration of the nature of a particularly Jewish manhood or a present/future where sex, gender and associated roles are more fluid. I won’t get too far into that, because there’s plenty written about the feminised Jewish male body (particularly the sick one) and the responses and reactions — from Max Nordau’s ‘Muscle Jew’ to hyper-sexual and sexist posturing of Roth’s protagonists underscored by neurosis and onto the macho, gun-wielding Paul Newman as Ari in Exodus. Leivick’s physically weak scholars, too, will eventually team up with their labourer counterparts and fight in Miracle in the Ghetto.

The work of Jewish immigrants is not necessarily conventionally American ‘masculine’ heavy labour either — with both men and women employed at sewing machines, in shops. In The Poet Went Blind, a male character offers to complete his sister in law’s home piecework to feel the validation of work while his own shop has none to offer, an interesting sort of ambiguity between men’s work/women’s work.

Male tenderness and its expression — or lack thereof— reoccurs constantly in Leivick. If anything, while Leivick can approach the erotic in writing, physical intercourse seems to consistently be portrayed as disturbing, frightening and violent. It’s often made into a perverse act: Leivick’s Abelard runs away from his parents having sex, it seeming to distress his mother or cause her pain (it is difficult, perhaps, to disentangle this particular image entirely from Leivick’s descriptions of his own childhood home and self-reported desire for his parents to stop having children, just as it is hard to separate his dramatic/poetic images of brutality visited on bodies from more factual descriptions of his own experience). In Redemption Comedy, monstrous group sex with a stone shaped like a woman results in Armilus, the rather inconstant prophet. By contrast, Dvorel and Hanina (the Moshiach Ben Dovid) conceive a child without touching — both played by women in the only (Habima) staging.