Following on from a poem written in Minsk Prison last week, this particular reminiscence is drawn from an article by Moishe Shulmeister (there’s a bit more to it than what I’ve translated here) for the Freie Arbeiter Stimme.

It was 68 years ago, in 1907, in Minsk.

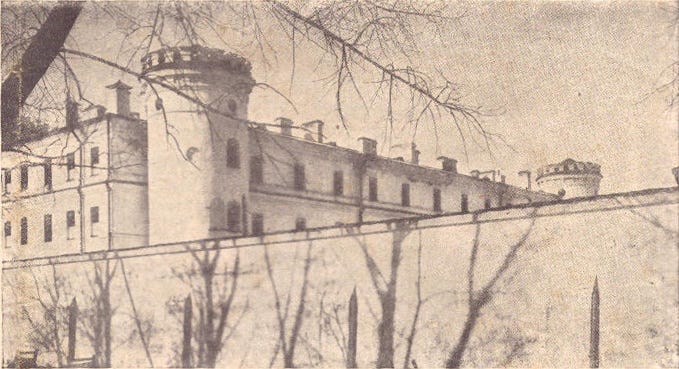

H. Leivick, who was then called Leivick Halpern, had been arrested a year earlier for the second time for his socialist activities. And I, who they called ‘Polzhidek’, had fallen into the hands of the Tsarist police through a provocateur who gave away those who worked in an underground anarchist press. But in 1907, we both met in Minsk Jail, where we awaited a convoy to be led to Siberia to katorga.

Soon after our first meeting, Leivick became curious to know from where I had received the nickname ‘Polzhidek’.1 I told him that nickname wasn’t mine from the outset, but it had belonged to my boss in a Bialystok weaver’s, where I had worked. And he had indeed been called by that because he was a small, short little Jew. But later, during a strike, and a fight because the Polish weavers hadn’t allowed any Jews to learn to work on the newly-arrived machine looms, someone stuck my boss’ nickname on me, even though I was almost twice the height of the original ‘Polzhidek.’ And so the name had remained with me in the revolutionary underground.

Our prison cell was a large one, with about twenty political prisoners, and we benefited from all the same privileges there as such prisoners had a right to under the Tsarist regime. Several of us were, from the beginning occupied, in their own deep thoughts and worries. But bit by bit we grew acclimated to our prison comrades and sought means to keep away the terrible boredom. We used to play chess and also occupy ourselves with other pastimes. Several of us, understand, wrote letters. But Leivick used to write the most, especially at night. I remember how he used to sit down a while, write a line or two, and soon get up again and walk around the cell, until he once again sat down to write a minute or two.

At the beginning, a portion of the prison comrades used make fun of him. But with time we grew accustomed to Leivick’s manner of a write and a walk and a walk and a write, and our mockery was exchanged for respect.

We used to, from time to time, organise entertainments amongst us in the prison cell with our own amateur talents. One sang, another danced, a third recited, a fourth performed tricks, and so forth. When it came the turn of Leivick to entertain us, he had chosen to be a melamed, and he made me his student. And he taught me Chumash, only not a harsh lesson, but the Parsha Tazria.

But as we had no Chumash, Leivick taught me by heart: ‘If a woman conceives and gives birth to a male …And on the eighth day, the flesh of his foreskin shall be circumcised.’ And in every prison cell, there were so many Jews — SRs, Bundists, Maximalists and Anarchists — and almost all of them rolled with laughter, hearing how Leivick explained the holy words and especially how he had answered my foolish questions. Leivick’s ‘performance’ had been so welcomed by our prison comrades that we replayed it several times, although each time, Leivick selected a different parsha of the Chumash, which allowed him to explain and explain to play out the fantasies of healthy, sexually-starved youth in prison.

Through those performances, I became closer acquainted with Leivick, and we often used to talk about our underground activities and about our prison terms. He told me that if he hadn’t been so stubborn and insolently provocative before the judges, he certainly would have received a much smaller sentence. But Leivick had, just before, firmly decided not to beg any mercy from the Tsarist judges and not to show the least regret or submission regarding them. And he was indeed sentenced to four years katorga and lifetime exile to Siberia.

Several weeks after the severe sentencing, Leivick— as they later did with me and the other political prisoners after sentences were carried out — was smithed into chains and after having served a year in Minsk Jail, they took him away to katorga in Moscow. After serving his katorga term in Moscow, he was taken in convoy to Siberia.

Leivick was taken away by convoy to Siberia before they did so with me. When, several years later, Leivick escaped to America, I was still in Siberia. But I held a written correspondence with him. And as my parents know didn’t where I had disappeared, because I had been arrested on a false pass with a strange name, I sent a letter to them in my hometown, Kleshtshel, through Leivick in America, and he sent my letter home. Kleshtshel was a tiny village near Bialystok, and when my letter from America reached my parents, there was a great joy in the whole village, because everyone there was certain I was already dead after so many years of not hearing from me.

Several years later, during the First World War, I also escaped from Siberia. But as I dragged myself home, the Russian Revolution had already broken out, and in Kleshtshel the Jews were dying of hunger. When my parents saw me, my mother fell on me, weeping. But my father said with a bit of angry surprise: ‘at such a time you come here from America?!’

In 1923 I indeed truly arrived in America. Understand that I soon went to Leivick, who then lived in the Bronx. Firstly, he told me that a girl from my hometown had asked after me to him several times. She really wanted to see me. And she hadn’t believed him that every letter from New York had really been sent from Siberia, where I then still remained.

Over the years in New York, we met less. I became occupied in my own matters and worries. But my contact with Leivick continued through his literary creations, which for me had a special flavour and meaning. It always somewhat seemed to me that I was related to them. I had the honour to see how Leivick the poet was born and created in a prison cell of Minsk Jail.

I’ve incorporated the minor corrections to the article which appeared in the following issue.

I’ve not encountered this particular information anywhere else before, but in an issue which follows shortly after this one, there appears a letter by Daniel Leivick saying that his mother, Soreh Leivick Silverberg, reads the paper and has urged him to send them a donation on her behalf. I do think that if anything had been grossly incorrect, there would have been further corrections — but can’t speak to the accuracy of the story at all.

Both Daniel and Soreh died in 1976 and the paper itself shuttered in 1977.

Half a Jew.