In the Days of Job, Part One

‘How does [Man] bear the pain of the other people across the entire world?’

S. Raskin’s title page for In the Days of Job, 1953.

Onward to In the Days of Job, Leivick’s last complete, published play, from 1953.

There are, apparently, fragments of at least three other plays at Yivo, of various vintages — one about lamed-vovniks, a subject about which he was threatening to write as his last play c.1954 in interview with both Y. Pat and A. Tabachnick, one about the Moshiach and one which touched on prison again forum 1914.1

Just as I lag about seventy years behind Shmuel Charney on just about all of Leivick’s work, I am far, far behind William Natanson on this one. Standing on the shoulders of giants, ha? This isn’t by any means so measured and academic response to Leivick as any of their writing (or Tutshinski or anyone else), just my reactions as I go swimming through about forty years of his professional writing career, occasionally diving.

It isn’t surprising in the least that Leivick values the psychic wound. He’s got a deep and very personal relationship with trauma. And the trauma, as reflected in his work appears to have several origins: that of childhood poverty and abuse, antisemitism and pogrom, the accidental (and hideous) death of his sister, his beating by the police (both his interview with Yankev Pat and S. Charney’s critical biography mention an arrest at sixteen where he was forced to run a gauntlet all night after being arrested at a Bundist protest) and eventual arrest at eighteen, prison (he has ongoing nightmares and paranoia, seemingly, about the door being broken down and being arrested), escape from Siberia, immigration, serious illness requiring prolonged hospitalisation…not very hard to see why he gives equal weight to the psychological injury.

I would also argue that he is constantly in search of wholeness — something to ‘complete the circle.’ Sometimes, he cannot integrate the versions or shattered pieces of self — and as a result we see bodies hacked to bits, broken apart into sand, scattered, people who walk away from their lives (and remain both living and dead simultaneously). Like him, his characters are often in search of some form of wholeness or completion. In Abelard and Heloise, Abelard says that he sought his ‘whole person,’ stronger than him, to hold him together — his Heloise.

And this brings us, in a way, to In the Days of Job.2 Job, of course, has been attacked on both fronts, the physical and the mental. He is no longer whole.

But we don’t start by meeting Job. We start, after some initial set-up for the character of ‘The Adversary’ or ‘Satan’3 (also present in Leivick’s Chains of the Moshiach and in Akeydah), with Abraham and Isaac.

How do we get to Abraham and Isaac from Job? Leivick tells us exactly how.

Because everything works according to a logic — and usually a scriptural or traditional reason — it’s just a matter of which/whose. A Jewish reading of Leivick (even a largely secular one, like my own) is a different affair than a non-Jewish one. Sure, he’s macabre, grotesque, lurid, leading one to believe that he is perhaps, as sometimes accused, masochistic. He’s got monsters: golems, werewolves, the undead. Floods of blood. But there’s a traditional, religious grounding for all of it. Just pushed beyond usual constraints into its logical, if bloody, conclusion.

In Maharam of Rothenburg, the titular Maharam tells his captor (and the audience) how it is that the play wanders through time and how it’s two timelines intersect and interact. There, it is both dream a mystical power, given to those enlightened enough to do it — the characters of the play, and the audience, are granted this privilege.

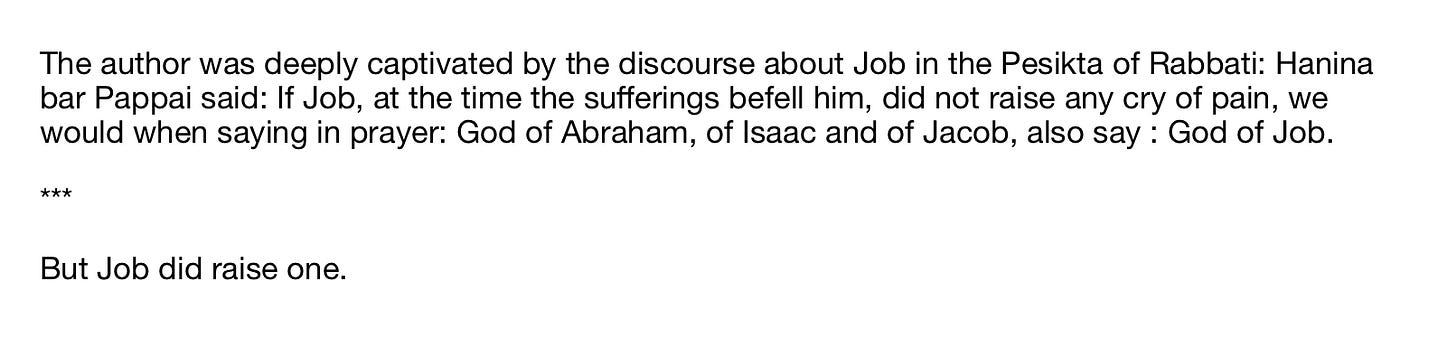

Here, In the Days of Job, it’s a simpler, pre-extant affair. In the Talmud, in Bava Batra, there is a discussion as to when it was that Job actually lived (making Job, perhaps, a bit of a time traveler himself?) and this, Leivick says, clears his path.

From Leivick’s introduction to In the Days of Job.

The fact Leivick takes the time to explain this textual reasoning is telling to me — citing his sources, like a good scholar, rather than just claiming pure poetic license — that you miss a large chunk of what he’s doing without some understanding of what’s feeding the work culturally, as well as in terms of personal history. And if you read enough Leivick, in my limited experience, he does eventually tell you what’s making him ‘tick’ in a certain circumstance.4

The phrasing from Bava Batra, though, is slightly inverted, changing the focus. Rather than Job living in the days of Abraham, Abraham and Isaac are living in the days of Job. Job, as Leivick says in his introduction, perhaps could have been included in the patriarchs:

From Leivick’s introduction to In the Days of Job.

Job begins this howling at the latest afflictions delivered by the Adversary and there is something very particular about the nature of his call: only those who are sufferers, in some sense, can hear it: Abraham’s blind and lame servants (in fact, all of the disabled) can hear it. All of the over-loaded and beaten beasts of burden, too, can hear. Abraham cannot, nor can his healthy shepherds, barring the initial storm which casts darkness over the land.

But the two disabled servants and Isaac can.

Why can Isaac hear? Because he’s one of the ‘wounded,’ too.

Leivick’s language regarding physical disability is very much of it’s day, and so I’ll try to avoid it as much as possible. His concept of the disabled as having some moral and spiritual power beyond that of able-bodied people also isn’t great.5 I’m not out to absolve him of either here. It’s problematic. No way around it.

Isaac is able-bodied, though, the Adversary tells us, looking sadder and more lined than the last he saw him. Which was at Moriah.

The Isaac we meet here is three years out from the Akeydah, the death of his mother upon his return, and awaiting the procurement of a bride6. Abraham ends any attempt he makes to either speak about either the attempted sacrifice or Sarah’s death. Isaac can achieve no emotional healing and isn’t allowed the emotional catharsis of expressing his anger and his grief by Abraham until it’s too late, until he’s made up his mind to go and follow to the cry back to Job. Abraham, we know, has the consolation of promised generations to come (which he has set about trying to achieve in sending a servant to find a wife). Isaac has no such direct promise, no such personal relationship.

In The Days of Job, Scene One.

Only at that last moment does Abraham offer him the chance to speak about his own injury, his pain — but the more attractive force and voice now is the one which has begun to scream. The one which can express its grief in some form. The scream is almost tangible.

Again, highly temping, even in light of Leivick’s warning that he doesn’t put all of himself on the page, to draw parallels between a young would-be poet and revolutionary who didn’t see eye to eye with his father on many things, including God and how to relate to him. Who was sometimes taunted, at least as a Leivick tells it, for being too silent. This play, in fact, is dedicated to Leivick’s own sons, and prefaced by a poem to a grandson. I don’t think it’s too dangerous to suggest some connection between personal experience and what appears on the page as he draws some of that line himself.

Here I’ll jump back to the animals a bit. We meet a donkey and three camels who have absolutely had it with being beasts of burden. They want an accounting of what has been done to them. In fact, almost everyone in In the Days of Job is out for their kheshbon.

This idea of an ‘accounting’ isn’t new to Leivick. Sometimes, there’s an internal stocktaking — the kheshbon hanefesh. But there’s also the external one, for what one has suffered. Heloise demands such an accounting for every tear and drop of blood shed by Abelard. Even as far back as 1908’s Soul from Hell (it’s alternate title is ‘Job the Second’), Leivick wanted accounting and recompense for his people’s uncompensated suffering.

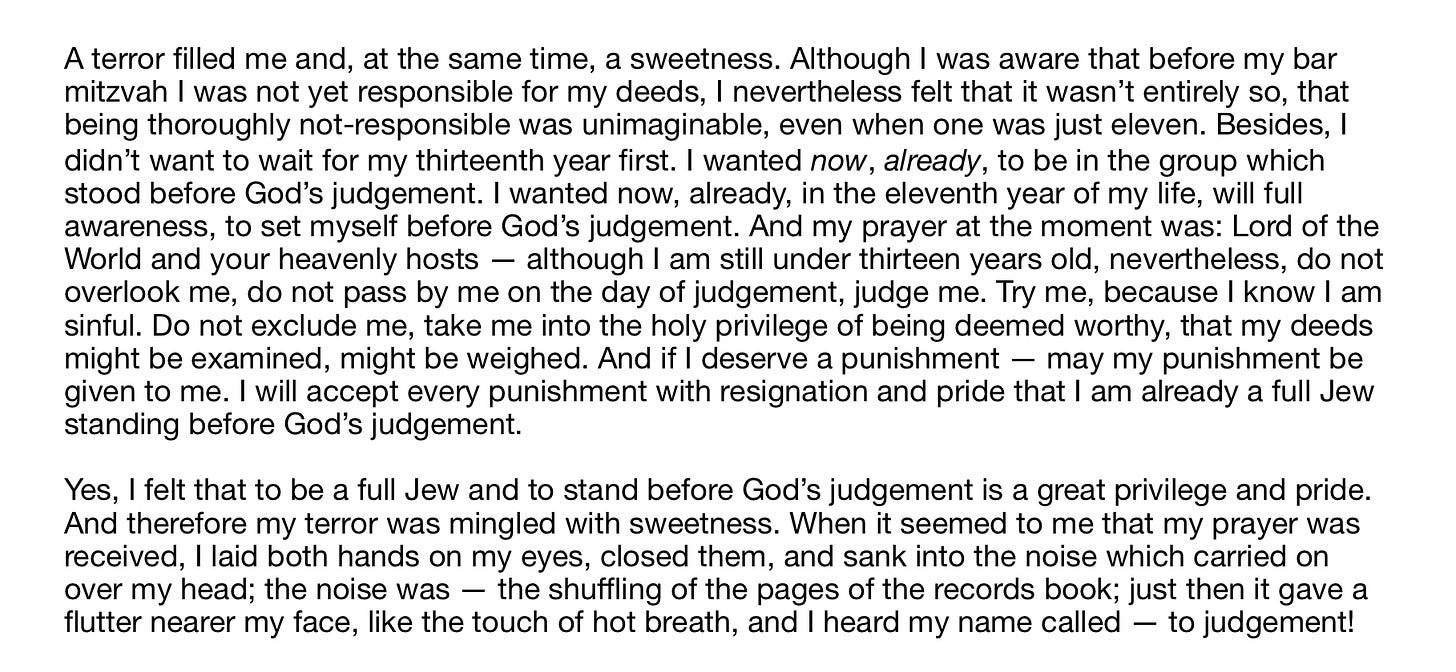

In essay, Leivick recalls his wanting to be called to account on Yom Kippur even before the age of responsibility.

From Essays and Speeches, 1963.

Judgement and accounting are almost always there as a thought and guide.

In some ways, this is a play about the personal accounting, and the accompanying loneliness: that of those who find the responsible and the attendant grief of that responsibility.

Isaac is lonesome. He doesn’t have the relationship with God that his father has. He doesn’t truly have peers. Certainly no one else who was bound on an altar and only saved from sacrifice at the last moment. His mother is dead and he is grieving her in a way which is rigidly defined by his father, not by his own emotion. He awaits a bride he has never met, but been promised.

Job, for all that he still has his wife and his three friends, is also isolated and lonely in his suffering. Because everyone truly suffers alone.

The Adversary implies, though, that it isn’t only the humans of the play, but God who also walks as a lonely sufferer amongst the suffering. And Leivick speaks elsewhere about his concept of the loneliness of the creator (in relationship to Golem, in interview with Pat). The poet too, he says, can retreat into himself, must do so, and works alone.

From Essays and Speeches, 1963.

Isaac’s psychic wounds are again compared the physical disabilities of those around him. This injury is treated as equally crippling in some aspects. But there is also the secondary idea introduced, yet again, that there is some moral superiority granted by the physical disability which is not conferred by the mental one received through trauma. The possibility of future physical disablement is held out as an almost ecstatic religious experience here as it is elsewhere in Leivick — that Isaac will become blind so that the fire of Mount Moriah, and only this fire, remains in his sight forever.

In Isaac’s vision, though, which we, the audience, see from both sides, there is a representation of how this psychic wound initially manifests — as the fragmented self: Scene three closes with Isaac receiving a vision of Rebecca and Eleazar and Scene Four opens with Rebecca and Eleazar, riding through the desert. There, a supernatural figure appears to them — one who is both Isaac and not.

It is, the figure says, Isaac’s sorrow. Certainly not the first time we encounter a disembodied spirit. The unformed spirit of the Golem, for example, warns the Maharal not to create him as he does not wish to be pulled from his, apparently pre-extant, rest.

Leivick himself seems to have several episodes which might be described as stepping out with of one’s body, a notable one occurring in With the Surviving Remnant, but also in In Tsarist Katorga. Even in poetry of this period, he touches upon the image of being able to pass through walls, freed from physical being.

From Leaf on an Apple Tree, 1955.

This apparition of Isaac tells Rebecca that Isaac sees a second leading to the Akeydah — hers.

To be Continued

A portion of a proper translation by Leonard Wolf is available in Howe and Greenberg’s A Treasury of Yiddish Poetry, 1969.

I’ve left him at the Adversary and call him so throughout to divorce him from the Christian idea of Satan, which he is most definitely not.

In interview with A. Tabachnick, Leivick mentioned the possibility of writing a book with ‘biographies’ of some of his poems. I don’t know if there’s anything in the archives, and he does it a bit with ‘Ergets Vayt’ in the interview, but it seems to have come to nowt. Which is a pity.

Primarily, he seems to suspect that they are, or potentially are, lamed-vovniks, the secret holy people, numbering thirty-six, upon whom the continued existence of the world is predicated. I still have Beggars/Poor Kingdom on the slate, where disability takes a more central role.

Leivick’s going with Rashi’s estimate of Isaac’s age at the Akeydah here, making him now about forty.