Leivick in Eretz Yisroel 1937, Part 5

Yiddish and Hebrew Are Two Rivers, Which Flow From The One Spring; There Exists A Deep Commonality Between Them

Back to Part Four.

Yiddish and Hebrew are two rivers, which gush from the one spring; there exists a deep commonality between them

— An evening with Yiddishists and an evening with Hebraists. — No, there cannot be any hatred between the two languages if we wish to maintain our national character. — Without Warsaw, Paris and New York, Eretz Yisroel cannot be, either. — Is the collapse of Yiddish the disintegration of the entirely of Jewish life? — The speeches of the Israeli writers in Hebrew, and my reply in Yiddish. —

With the Hebrew PEN Club, in an intimate hall, with decked tables. There are assembled about two hundred people. Most of them are Hebrew writers, also some younger Yiddish writers. A portion of guests, as well. The president is Shaul Tchernichovsky.1

I have much anticipated this coming together, and innerly prepared myself for it. To me, it was clear that I hadn’t come to Israel with intentions of provoking Hebrew, of waging a linguistic war. Yet before I travelled, I had the sense that Eretz Yisroel currently had certain problems and worries which came before the language problem; and now that I had arrived, I felt it even more strongly.

Arab terror, attacks on the road and on the kibbutzes, halted immigration, increase of unemployment, English politics, the partition plan. From all of this — wound and strained nerves.

One gets up in the morning, takes a newspaper in hand — immediate searching to see: Where was there an attack? Was anyone killed? If killed — how many?

The local residents are already acclimatised to the situation, are not so nervous as the newly-arrived. So they tell me. And it’s probably correct. But the news of attacks, shootings, stabbings, makes an impression on me, and everything in me tenses into one desire, almost like a prayer: That it ought not be and how it ought not be — but firstly, cease murdering, hidden, lurking murder! And even though you call it by the name of terrorism, all of your murder is no more than murder, criminal, savage, murder. Innocent men, you attack, women, children, old people — indiscriminately.

In such a mood and in such an atmosphere, in the presence of curbing patience and worry from everyone to not lose control of patience, not to collapse into a spirit of forlornness and in lust for vengeance — posing our linguistic-struggle as an aggravation of all the questions is both senseless and lacking in tact.

But taking it up it in a normal manner, in an atmosphere of friendship, directly, with the sole intent only to understand, because it touches the very essence, the soul of our cultural life — this, I was convinced, needed to be done. Better said: if it will happen itself, it emerges itself, and falls into a state of too much caution, above all, due to the political situation in the country being entirely equivalent to the situation of Yiddish in Eretz Yisroel — it would be no less untactful.

Yes, I was indeed impressed by the wonderful revival of Eretz Yisroel, was impressed and excited. Received love. But this cannot and may not distract from the great sin which Eretz Yisroel commits against Yiddish…

And Eretz Yisroel sins against Yiddish now, too.

Most difficult of all for me to understand and grasp, how writers, creative people, who know the intimate nature of the word, who know the internal quivering of creation, that language is not merely some external clothing that may be taken off and cast aside — how can they be decided that Yiddish ought to be in an official state of oppression? And still more — how can they be decided that Yiddish ought to be in a state of suppression?

I emphasise that the suppression of Yiddish in Eretz Yisroel, the guilt for which falls, above all, on the writers and teachers and not on the common people (the common people love Yiddish and there is no conflict with Yiddish) bothers me more than the oppression. That is to say, the psychological relationship more than the political one.

Therefore, I waited with great interest for this coming together with the Hebrew writers. The opinion of the Hebrew writers toward me didn’t concern me. Their opinion of me, I felt immediately upon my arrival in them country, was warm, close. I went in that dream of joint peace, of closeness of both our literatures and fraternity of our cultural-spirit, about which I dream for the present time.

I also underscore here: Cultural-spirit, because cultural-spirit disturbs me more than cultural-force, than cultural-victory.

The night before the meeting with the Hebrew PEN club, I had a meeting with the Yiddish literature club, that is to say, with the Yiddishist writers in Israel — coming together in their small premises. Two small rooms. It was quite cramped, but close and intimate and — sad. Yes, the assembly of Yiddish writers that evening in the Yiddish literature club left a sorrow behind in me. Together with a joy from everyone’s hearts, through everyone’s speeches (Zerubavel, Erem, Leybl, Papyernikov, Rubin, Golomb, Shtol, Isban and others), there resounded such a sorrow, such a lonesomeness. Choking words burst from their hearts with unbounded love for Eretz Yisroel, struggle, wishing to fly, wishing to have an effect, wishing to embrace everyone, all the places, all the mountains and valleys and — strike against the walls of tiny premises, become wounded, fall down, still and bloodied and remain lying on the threshold.

Did you see the bloodied words? The still, still, bloodied Yiddish words?

Tel Aviv, beautiful, white Tel Aviv, why don’t you hear how the longing poets sing to you? Why don’t you see how they love you, how the spread their arms out to you, how their eyes are filled with fervent yearning for you, with fidelity, unrewarded fidelity?

Because who is yet so unrewarded by you as them — the Yiddish writers?

Now I see how they burn, truly like a fire, the eyes of the young Yiddish poet Shamri.2 His face is tense, his lips — closed, his shoulders trembling.

I cannot forget that young poet from Ein Shemer, who kindles his life with exacting poems in Yiddish, living and working on a kibbutz which carries on in Hebrew.

I left the gathering with the Yiddish literature club with a trembling through all my limbs. I will say it more openly: I left broken.

The impression of the gathering with the Yiddish writers did not leave me the whole of the following day.

And under that impression, I went to the evening of the Hebrew PEN club.

It’s no necessity to talk during the evening precisely about the language question, — I said to myself, — but if it should begin to speak of itself, that is — otherwise. Why not?

Tchernichovsky opened the evening warmly and solemnly. Then spoke Y. Fichman, S. Ginzburg, A. Shlonsky, N. Greenblatt, Ever Hadani and to close, myself.

Everyone’s speeches were about me and my writing, and it isn’t the place here, naturally, to bring them up. Only one speaker, N. Greenblatt, had amongst other things, touched upon the struggle of Yiddish and Hebrew, mentioning Opatoshu with a grudge, that he, according to Greenblatt’s thinking, left Israel unsatisfied, with a hostile attitude toward Eretz Yisroel. To close, he brought up an interesting thought, that Yiddish continues in pursuit of Hebrew across the world, pursuant and insulted and so forth.

All spoke in Hebrew and I gave my speech in Yiddish.

It appeared all was in order, all was celebratory, Hebrew writers speaking Hebrew, a Yiddish writer speaking Yiddish. But behind my back stood my invisible escort and continued whispering: There is something out of order here.

And indeed, perhaps not — I admitted. The colleagues talking to me and about me, it was vital I ought to understand the least nuance of the speech — and here I understand only the general course of their talk, but the intimacy of the word I do not catch, particularly because of the Sephardic pronunciation. Of ten words, I catch two or three. This is a great shame. And how do they not feel it? They — poets, novelists, fine, profound men sacrifice true human intimacy for the sake of an official stance!…

— Dear friends, — I said, — I will speak Yiddish. Chumash Hebrew isn’t foreign to me, and I don’t deny that I’ve caught the gist of your talks, but the details, the nuances of your speeches, did not entirely reach me. I have received the tone of your warm praise and also your reproach. It is true that this moment, when I am with you, will remain in my memory a long while. Not often is such an encounter made in our lives. There exist those who think that we are opposed, almost hate — no, I say, no, this isn’t true.

I have perhaps not at all wanted to involve myself today in the question of language, but you see yourself it cannot be avoided. I do not want to consider myself an accidental guest among you.

When I visited the Tel Aviv City Council yesterday, in the visitor’s book I signed my name, adding: Both a guest and a resident. Yes, I feel that along with you, I am a rightful citizen, because I see the Jewish life of the entire world as one great unity. In our souls the concept of exile mingles like a cancer. A cancer and a hump. But I am of those who wish to throw off that hump. We don’t want to carry the word exile on ourselves and negate Jewish life, Yiddish language and Jewish culture in the world. It isn’t so easy to achieve it. I equally bear, like all, the fight and struggle, that our generation leads — a generation that doesn’t wish to yield.

— That which is accomplished by a Jewish person in other countries, in America, for example, all efforts in the struggle for Jewish culture, for Yiddish language, for Jewish culture, literature and schools — this is the great fight which was led by us for the upholding of our national personality.

If you, building this new Jewish life here in Eretz Yisroel, consider well what Yiddish accomplishes for the entirety of a Jewish life in the world, it wouldn’t be possible to create such contradictory boundaries between us there should take root a crazy thought, that we are two sides which cease to war between one another. One certainly wouldn’t need to talk about it. It’s self-evident.

— What was our life in America fifty years ago, at the beginning of immigration, and what is it today? If you would reflect upon the differences, in the great development that Jewish culture and literature have undergone — if you’d imagine it well, you’d see then to what sort of wonderful strength Yiddish has risen, from a lowly jargon to such a song, to such an intimacy.

And you’d see how much energy we’ve all expended for the elevation of our folk-culture.

The American chapter is one of the most wonderful chapters in the history of our people. We still wait upon the great artist, who might depict for us the profound drama which calls itself: Jewish America.

— We also see the Eretz Yisroel chapter as a wonderful sight, like a tapestry of the entirety of Jewish life in the world and — as a great influence. And here we differentiate in our approach and evaluation. Here also begins the conflict of both our languages, and here also begins the danger of an inner division, of a falling apart into two foreign sides.

— You mentioned Opatoshu here, and mentioned him with criticism. But you’re all committing a sin if you think Opatoshu’s against you, against Eretz Yisroel. It isn’t true. It is stunning and a great pain if there can be created such a situation and such thinking that one of our most important Yiddish writers, if he published certain critical thoughts about Eretz Yisroel, he is already reckoned by you an enemy of Eretz Yisroel.

— You say that we continue to war against Hebrew, that we persecute Hebrew. This is certainly, certainly, not true. (The state of Hebrew in Soviet Russia doesn’t enter into it, because with Soviet Russia we have accounting not only of Hebrew writers, but also Yiddish ones).

— We, Yiddish writers, hold by the contrary, that Hebrew was always on the offensive regarding Yiddish, and Yiddish always continued to defend itself. But we aren’t here today to accuse one another. It’s a comradely conversation. With my coming here, there revived in me my desire to weave myself into your lives, into your stories. And, in truth, I have found more than I imagined here. I’ve seen a new will here, felt new Jewish strengths, a bright revelation, and it raised still stronger in me the hope to find a bond between all creative Jewish strengths, an understanding and a unity between us. Because, in truth, the danger of rupture follows us.

— I recall twelve years ago, travelling in Warsaw with colleague Fichman, we conversed about putting out a united anthology, Yiddish and Hebrew together, in joint translation and, with this, making an attempt at abolishing the distance which rules between both our literatures. I, of course, didn’t think this would bring us full salvation, but it would’ve been a good attempt. Now it seems to me, though, that colleague Fichman no longer considers it. (Fichman fires back: We’re all very busy here ——).3

— We, too, don’t go about idly in America. We also do things in America. Still more: Many Yiddish writers in America are labourers. And you may consider the following thought: If it were not for Warsaw, Paris, New York — there would also be no Eretz Yisroel. If our hoping to maintain in the world a high cultural standard in Yiddish should, God forbid, collapse, — the entirety of Jewish life would collapse, Eretz Yisroel would collapse, as well. And I say to you, colleagues, if Yiddish should die, Hebrew will also die. And the converse, as well. Without Yiddish, Jewish life today is absolutely nothing. The great struggle which Jews lead in the world — from it also comes Eretz Yisroel. Our awareness is: We’re no longer strangers in the world. Not anywhere. We don’t want to be. Should we wish to be again — history will be revenged upon us.

— To me it seems that the Hebrew writers, considering the Jews of the entire world, say to them:

— How displeasing you are to me today; I hate you, I deny you. I want to see another Jew instead of you, a new one.

This is an unlovely situation. The average Jewish person should be rubbish before the Adam Shalem, before the Adam Elyon.4

And the Yiddish writers say: I love the Jewish person as he is, with all his contradictions, with all of his lackings, I don’t want him to be as rubbish beneath the feet of life.

Can there be an understanding between both literatures? Certainly there can. And not only can there be — there must be. The two approaches to the Jewish person must influence each other.

Yiddish and Hebrew are in essence two rivers which flow from one spring, there is a deep commonality between them, and in light of this communality, we must look differently upon the literature, upon the culture, upon the school. (K. Silman hits back: You want, it seems, Yiddish in Eretz Yisroel?) — Yes, I want Yiddish in Eretz Yisroel too. I’m not trying to provoke. I didn’t come here to wage a war. I’m not anyone’s emissary. I speak in my own name. I take the matter historically. And I speak about historic necessity. How to attain this unity — I have no prepared plan. But I feel the necessity that the bridge should be erected all the quicker, and if my talk should provoke you into even considering it, I would feel happy.

Eretz Yisroel is a vision for all of us and a profound motif of the soul. Even the extreme Communists haven’t uprooted Eretz Yisroel from themselves.

Fate has willed that our lives be divided and fate wills also that they be united.

H. Leivick, Tog, 19 December, 1937

On to Part Six.

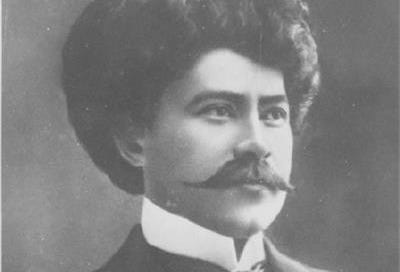

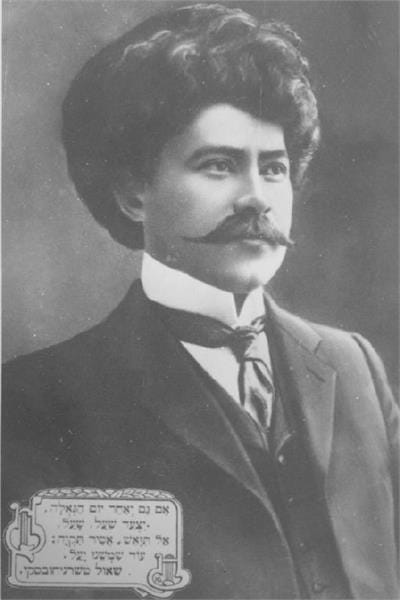

Shaul Tchernichovsky, borrowed from Wikipedia

Hebrew Poet. He and Leivick had spent most of the 1936 PEN Congress ignoring each other after Leivick’s protest against fascism, until finally leaving the final banquet together in disgust at the Italian futurists led by Marinetti.

The Shmuel Charney-involved Achisefer and the Louis Lamed Fund — bilingual anthology and a body awarding a prize for works in Yiddish and Hebrew, respectively — are still a few years off.

The complete person, the person in their highest, purest essence.