I have a particular weakness for pieces which deal with Leivick’s own past, the things which shaped him in some way — outside of the ways in which he clearly and forcefully shaped himself into his own creation — and how he chooses to speak about them. I also love his writing about other poets, friends, colleagues, even critics.

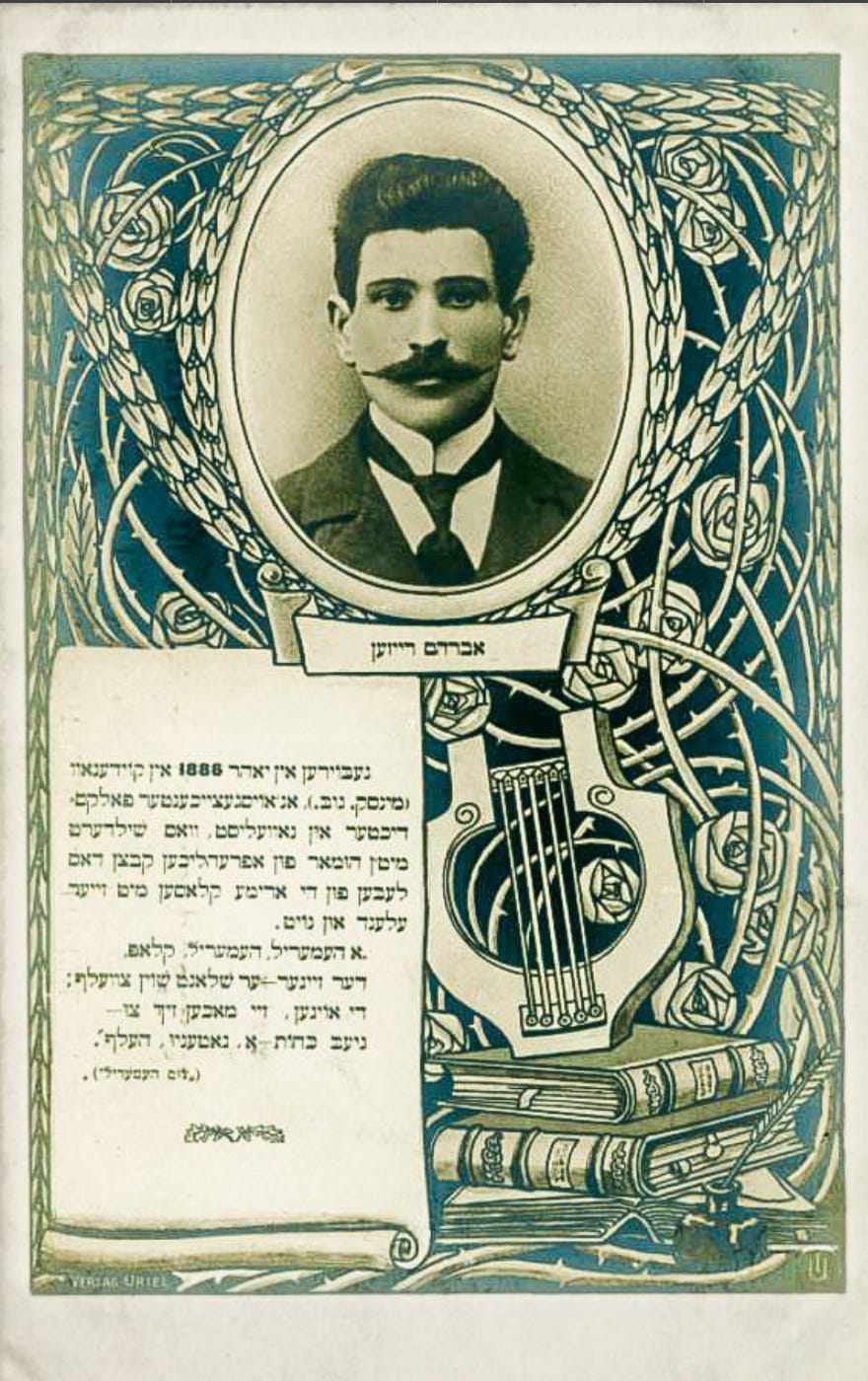

This piece, published shortly after Avrom Reyzen’s death on 31 March, 1953, combines the two. The poem Leivick focuses on in particular, ‘Household of Eight’ (he will mention it again in reference to his cell in Moscow’s Butyrka Prison, not just in reference to his own eight younger siblings) can be found in full translation here.

In The Years Of Bundist ‘Skhodkas’

We all accept that Avrom Reyzen belonged to a generation which emerged before us — that is to say: To the first generation of classical poets; even if the number of years which separates them from us doesn’t make up a full generation’s worth of years.

But this acceptance is correct. Upon him, upon Reyzen, there rested the light of the generation of I.L. Peretz. All of us, in the span of the decades that we have lived together with him in America as a poetic/literary family, have felt and treasured in him his belonging to the great pioneer generation, although, as more than one of us has already been seen themselves, through the eyes of a young poet of today, in the light of a twice-removed generation.

This is likely the way of generations. It indeed rings strange, extraordinarily, this word, generations, when you turn it towards the life and the creativity of people you’ve seen in the same street, sometimes under the same roof; you sat with them at the same table and suddenly they part and become generations — a respectful distance. A going away. A melancholy which stretches until the breaking of new dawn.

In our present sorrow — who can say how long the evening or the night will stretch; who can say where there waits a new dawn for our Yiddish literature? Who can say from whence it will arrive and if it will arrive?

* * *

An appraisal of Avrom Reyzen is not the intent of my few words today. His place of honour in our literature is assured; and today, when he has physically departed, we see his place at the head of the table filled with light.

It refreshes the memory of the distant past for me: My first acquaintance, in 1905, with his first chapbook of poetry and the first time seeing him in Minsk a year later, in 1906, when I went to him with my own poems, after I had already a notebook of Hebrew verses.

I was around seventeen years old. I was a member of the Bund ‘skhodka’1 in our shtetl. At secret meetings in the woods, we sang Yiddish revolutionary songs. Amongst them: Reyzen’s ‘Revel, Revel, Angry Winds’ and, it seems to me, also ‘Oh, Why Do You Ring, Church Bell’.

It seemed Avrom Reyzen was already who-knows-what-sort of an elder classical poet; it surprised me that I hadn’t yet encountered a single printed book of his and that I knew him only through a couple of sung motifs of his. I was already acquainted then with most of the works of Mendele, of Sholem Aleichem, I already had a full collection of Peretz in a single large volume.

I wasn’t aware that Avrom Reyzen, as a poet, was then only just in his very young, blossoming, ascent. I did foresee, though, that the entirety of Yiddish literature was festively ascendant.

Influenced, still in the yeshiva years, by Hebrew writers, such as I.L. Gordon, Smolenskin, Mapu, Levinsohn, Lilienblum, and very strongly by Bialik as well as Ahad Ha’am, I was, at the same time, no less affected by the Yiddish writers. There is existed no contradiction then. Both Jewish languages were natural. If only the later conflict hadn’t arisen.

It just so happened that we had bought a shipment of Yiddish books in Minsk and established a little library in our shtetl. I was appointed in charge of it. Amongst the books was also Reyzen’s first book of poetry. When one says book, they mean a large number of pages. But this was a small book. The number of poems limited. I took the book home with me, into my mother and father’s little house, and at night, when my parents and the children, four in number, excluding me, had already gone to sleep — mother and father in a room divided off from the house and the children in the general house, spread out on the floor near the baker’s oven — I started to read Reyzen’s poems.

As the eldest of the children, my parents made a bed for me on one of the benches around the table. It was no longer appropriate for me to sleep on the floor. On that bench, when I was at home, I spent my nights. By the little lamp, until late in the night, I was occupied in reading and sometimes also in writing. More than once, my father stuck out his head and started to rage that I sat up so late and sometime he would say that it was a waste of kerosene. He certainly didn’t so much mean the kerosene as that he was entirely displeased that I had quit yeshiva and gone down a road which would lead me, as he argued, to misfortune. My sitting at night over the little book oftentimes truly didn’t allow him to sleep. And sometimes, he was so overwhelmed by his displeasure that he, in anger, entirely avoided arguing with me and didn’t stick his head out at all to make his observations.

On a night like that, I read through Reyzen’s first book of poems for the first time.

It was already far past midnight. The children on the floor, nestled into one another, slept soundly. From father bed, too, there came no warning and no sound of anger. He was also fast asleep. My hard-working mother — certainly.

I was penetrated, through and through, by the poem I read. I was almost stunned. ‘May Ko Mashmo Lon’ [What Does This Mean To Us], ‘A Household of Eight,’ ‘My Life,’ etcetera, pained me with such truth that I was both as if wounded as well as if my soul had been illuminated by a song which began to sing to me from all the corners of the poor little shtetl house.

My eyes fell upon the children who lay and slept on the hard floor, and I suddenly saw them in a new, wondrous revelation through the lines of Reyzen’s ‘A Household of Eight.’

‘A household of eight — and only two beds; When night comes — where will they sleep?’

What does that mean — where will they sleep? — They lie here on the floor and sleep — and they sleep just as it says later in the poem: ‘Little arms and legs — tangled together’…

I looked at the children and saw: Correct! — Arms and legs tangled together.

And the poet, it seemed to me, had slipped into the house late, deep in the night. And now he stood and looked at his poem. He poem lay wonderfully made corporeal on the almost-bare floor — the tangled arms and legs of the children were fresh and well, ignoring that they slept on the ground; here they uncovered themselves and a radiance burst from them. A warmth, a sleeping peace, a nocturnal beauty.

And I thought to myself: See, this nocturnal beauty was probably also there yesterday, but it has only just been revealed to me now through the effect of the brief, confined lines of a poet’s song — there must certainly be a particular magic in the brief lines of Avrom Reyzen’s poem, in the austerity of the words, in the simplicity of the sounds.

Still now, after the the passage of nearly fifty years, when I think about that nighttime vision, I cannot turn away from the clarity of the vision. The warm, sorrowful beauty with which it pained me then, through the sound of a true poet’s word, still follows me today. And this is certainly a sign that in the poet’s lines there was both truth and beauty.

That which I relate has nothing to do with movement and classification. And the image of the children sleeping on the floor can certainly be presented in many other ways, in many other combinations and nuances. But the fundamental truth cannot be otherwise. Warm and nocturnally-bright young children’s legs must eternally be, even when they lie on the hard floor.

That warmth, the poet must give us in his verses.

On that night, another poem from the same Reyzen book penetrated me. I had started to read the book again, sitting at the table on my bench-bed and — I trembled as in a fever: ‘And my life is equal/ To a lamp with little oil —/ It does not go out/ To burn, it has no strength ———’

I look at the little lamp on the table, and my eyes peer into the small flame, the wick, the small magazine which holds the oil, and I begin to hear, truly hear, as the little wick with the yellow-red flame draws up the oily fluid, draws it in to itself and devours it. The little flame dances a bit under the narrow glass shade and spreads its light in a defined circle around it. The further from the little flame —all the darker the corners around the oven, where the children lie sleeping, are garbed in shadows; the little flame scarcely reaches them.

Deeply mysterious rustling carries to me from the shadowy corners. The house and all its souls, and I amongst them, is transformed into a great mystery. Breath crosses breath. Lives, although they sleep, rise, as though a wind lifts them. Lives circle around the little flame of the lamp and this flame illuminates them, this flame does not wish to go out.

The strength does not lie so much in the lamp as in the poet’s lines. They surrounded all the shadows and clad them in brightness. This was brightness of Avrom Reyzen’s verses, although for myself they were steeped in sorrow of knowing too early about his, the poet’s, own life.

I carry in my heart an eternal thankfulness to Avrom Reyzen, z”l, for that wondrous vision which he had, with his poems, revealed for me fifty years ago, and that they do not cease to be wondrous visions even today, after we have parted forever with the hand which wrote the poems.

By H. Leivick, Der Tog, April 1953

I don’t own the rights to this piece and it is presented purely from my own interest and a desire to pique yours. The translation (and any errors therein) is my own.

If you’d like to hear (and see) me rather excitedly talking about a couple of Leivick’s less-often treated plays and brief look the role of silence in his writing, you can follow this link to the recording of my talk for Farbindungen ’24.

Next week makes a full year of this, whatever this is!

Skhodka — a revolutionary assembly or council.