H. Leivick, ‘With A Visa From Yiddishland’ (Travel Notes, October 1936, Der Tog)

There are a few translations of Don Quixote into Yiddish — as you might expect from such a major work of world literature. If you search Yiddish Book Center, you get back three different editions and one ‘Tales from Don Quixote’. You also get back Y.Y. Trunk’s Simkhe Plakhte of Narkove or, The Yiddish Don Quixote. Suffice it to say that the bony old knight and Sancho Pancho (as he seems to be in Yiddish) are well and truly established in the mamaloshen.

Not just established, but even emblematic.

In terms of Leivick, we can see the figure of Don Quixote and his windmills in his poem ‘Yiddish Poets’. You can hear Leivick read the poem himself here. Here the poets are both childlike and ‘infatuated knights’ who tremble over every word.

Now, to be clear, Leivick broadly rejects the idea of chivalry in the sort of medieval or Arthurian revival sense. It’s profoundly un-Jewish. No offended honour that needs satisfied, no duelling to the death over a slap. It’s more than un-Jewish, it’s goyish — and he means that in the derogatory sense. Particularly post-war. Leivick includes the more modern duelling — such as the largely German and Austrian Mensur — that sprouted on the continent in this assessment. From an article for Tog in 1949 about the uprising in the Warsaw Ghetto:

But as we’ve seen with Sacco and Vanzetti (see Amelia Glaser’s Songs in Dark Times) and Abelard and Heloise, Leivick is perfectly capable of roping in anything or anyone he wants to make Jewish. I always think of this a bit like the ‘Cyclops’ episode of Joyce’s Ulysses; there, everything Irish is good and everything good is Irish. Here, much like Bloom’s refutation of the Citizen’s antisemitism in the episode, everything I (and you) hold most dear is Jewish.

In part, I wonder if this affinity doesn’t come from Leivick’s fascination with the Spanish Inquisition. He often references it, particularly in passages from Graetz’s history which Leivick tells us he re-reads in prison in Oyf Tsarisher Katorga. His continual return to the images of forced conversation, torture and martyrdom often prompt me to wonder why it was he never wrote a longer work on the subject or touched upon it in any of his dramas. Perhaps I’ll solve that particular mystery some day, perhaps not.

But does the Spanish Inquisition lead us to Cervantes?

Don Quixote does include a book burning, an auto-da-fé — a subject that Leivick certainly does touch upon, particularly in postwar years. But he’s already there, on Quixote’s shvel, before the war. Was it, then, perhaps Cervantes’ own trial and excommunication by the Inquisition? Did this afford him a bit of symbolic Jewishness in Leivick’s eyes? Was it one imprisoned author to another? Perhaps I’ll work that out someday, too.

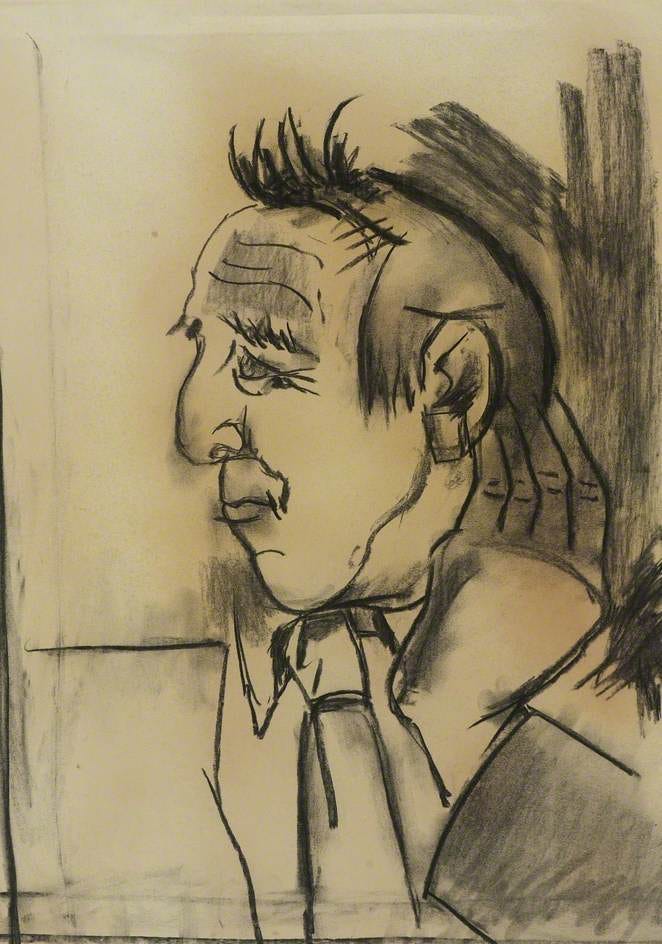

What is clear, though, is that Don Quixote himself becomes a potent symbol for Leivick, and a title he bestows upon those he likes best. We move from the general Yiddish poet to the specific individual. In 1947’s Mit Der Shayres Hapleyte (With the Surviving Remnant) we find one of these individuals upon whom he bestows the title: Avrom Nachum Stencl.1

A.N. Stencl, drawn by Josef Herman

When the delegation to the displaced persons camps, of which Leivick is part, is forced to stop in London for rather longer than anticipated, Leivick and co-delegate Israel Efros go to meet the local writers.2 Amongst them, of course, Stencl. They also attend (or, at least, Leivick does) a meeting of Stencl’s Friends of Yiddish group. And this is what he has to say about him:

Don Quixote and a lamed vovnik — one of the holy people upon whom the existence of the whole world is predicated, and another favourite theme for Leivick.3

Post-war, in the devastation of losing such a massive number of speakers and the ascendency of Hebrew,4 there is another group who joins the Yiddish poets as Don Quixotes: The Yiddish teachers.

And Leivick’s understanding of the predicament of the Yiddish teacher is a sympathetic and nuanced one. The Yiddish poet, the Yiddish writer, he says, is by nature solitary. They’d probably write without any readers at all. But the Yiddish teacher is in a different situation. Their job, their future, depends on the community and is woven into it. This future needs the pedagogical materials, the schools, the funding, as well as the parents and the homes to produce the students and send them. There’s no reader for the Yiddish poet — and no more Yiddish poets — without the Yiddish teacher.5

I think you could even push Leivick’s fondness for Quixote a bit further — is the plot near the end of Cervantes’ book of going off to be a shepherd with Sancho not a bit like Leivick’s imagining, as he stands at the foot of Mount Gilboa in 1937, the return of King Saul; Not to be king, but to be a shepherd again.

Leivick’s most sustained engagement, though, with the figure of Don Quixote — and with Cervantes himself — comes in A Blat Oyf an Epylboym (A Leaf on an Apple Tree, 1955). There, we encounter a cycle of four poems about Cervantes and Quixote set within a series of other poems about Yiddish and its future prospects. Leivick sails his ships with paper sails and the dives back into his copy of Don Quixote.

The cycle is, naturally, dedicated to the Yiddish poet, bringing us right back around to ‘Yiddish Poets’ and the early New York travails which Leivick captured there.6 And it kicks off with ‘Don Quixote’ (here in excerpt, rhymes not preserved):

After the initial long poem, Leivick ‘borrows’ the sonnet from Cervantes to finish his cycle. Cervantes gives him the form, Quixote gives him the tales of his fights against Satan,7 and he seems almost to become Quixote in the end, seeing his own face reflected in the mirror, without even a Sancho to advise or accompany him: ‘Don Quixote wages war with — Don Quixote.’8

Is it just another Leivickian double, like the Moshiach and the Golem who are indistinguishable in appearance from one another, but who turn upon each other? Is it akin to those meetings with his other selves and/or his own father? Or is it all those petty squabbles that Leivick sees as having kept Yiddish down, kept it fragmented, ultimately denying it its own higher educational institutions? Or the shift which sees Yiddish starting to be recognised at these institutions (see his own doctorate awarded by Hebrew Union College) while the average person is drifting away — as he puts it, reaching the high windows while falling out of the low ones?

Again, I think if you read enough of Leivick, he sometimes unpicks his own symbols and explains what he means. Here, in 1949, we see the knight at war with, in the end, himself:

A less positive Quixote, perhaps, but one all the same.

It becomes clearer and clearer as one reads as to why it is Leivick picks Don Quixote, out of all the other dreamers, fantasists and strivers of all of world literature, including Yiddish literature itself. It isn’t, of course, just his titling at the windmills. It’s about the great lady whose honour they do battle for: their Dulcinea. Leivick tells us precisely this in his series of articles about his visit to Israel in 1957, when a writer in the local press calls Yiddish a ‘handmaiden’ language.

Not all chivalry, it seems, is misguided or goyish.

Please go meet Stencl properly, he’s fabulous and has a very infectious smile.

Emma Schaver, the third delegate, is clearly bored out of her mind. Everyone’s a decade older than she is, had no interest in her, and she’s eager to perform for the DPs. Efros, too, isn’t thrilled, because he’s really a Hebrew writer and there’s no scene in London at all for him.

Leivick did, in fact, have a go at writing a drama about the lamed-vovniks, but it was never finished. There are a few draft pages, apparently, at YIVO. The theme also gets poked at in Poor Kingdom/Beggars.

There’s been so much ink spilled on this subject, digital and otherwise, that it would be silly of me to think I could really add anything to the argument. I’ll only point out that Leivick’s own warning was not to force people into Hebrew, because you’d only lose Yiddish: ‘I know America. Before a single Jewish home would be Hebraicised in the place of Yiddish, a thousand homes would be Anglicised.’

I specifically translate it as ‘Yiddish’ here, rather than just ‘Jewish’ because, in the context of the larger essay, Hebrew is also in play.

The poets go into those cellars after work in ‘Letter from America to a Distant Friend’ and re-emerge in ‘Yiddish Poets’. Sometimes, Leivick tells a story across a few poems, as in this cycle, sometimes, across a volume or two. And, if we trace the route from ‘Yiddish Poets’ to ‘Don Quixote,’ we see a thread sustained over about twenty years.

Important to recall that Leivick’s concept of ‘Satan’ isn’t Cervantes’/Quixote’s!

There’s a bit of an echo of his good friend Glanz-Leyeles’ Fabius Lind here, too: ‘Fabius Lind is at war with himself.’