Sentence, Part 1

The Ballad of the Desert

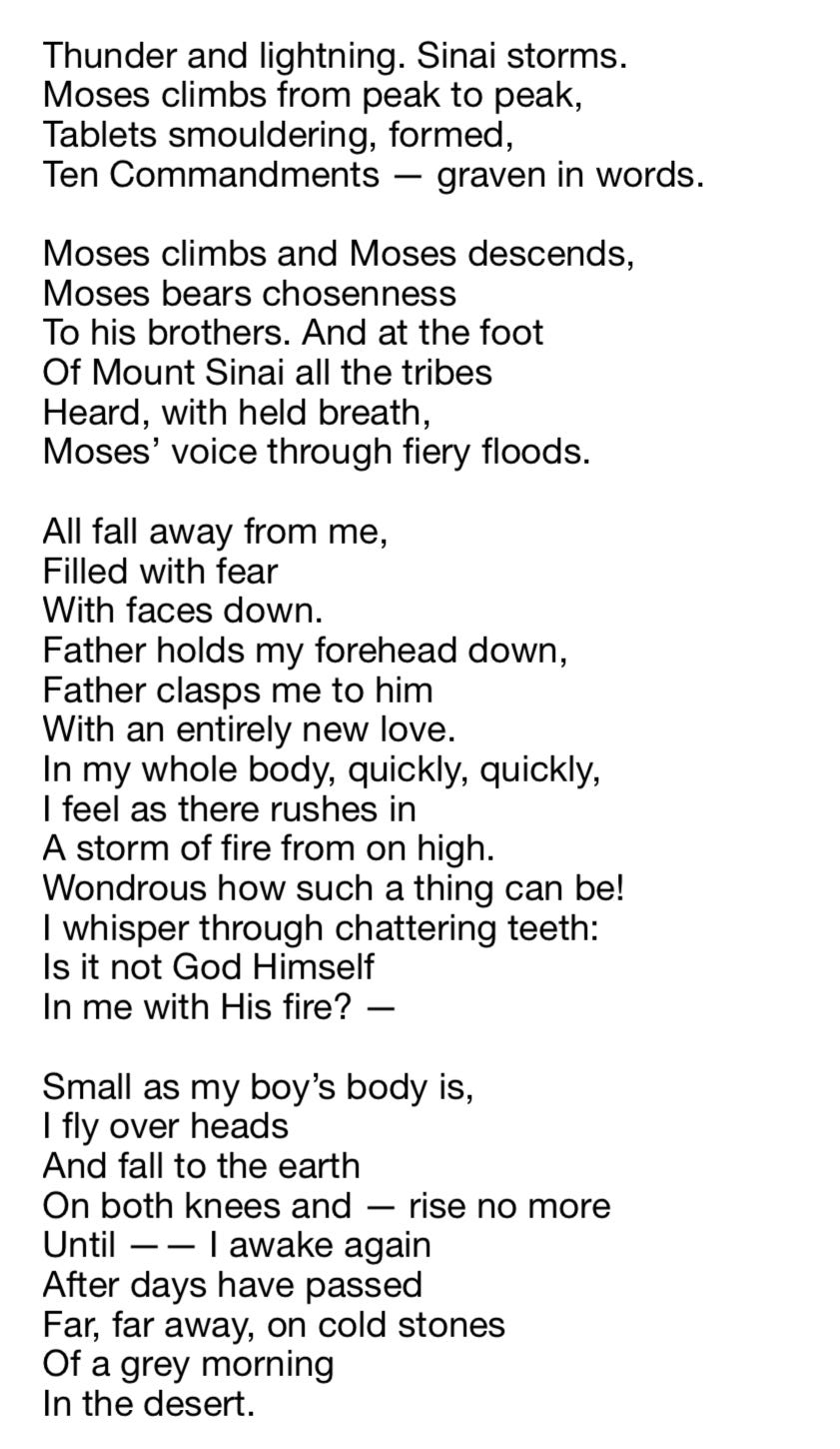

Lesser Ury, Moses Looks upon the Promised Land, 1928, Jewish Museum Berlin

Just as Maharam of Rothenburg and Miracle in the Ghetto (we’ll get to this soon!) are the products of a single time, 1944, so too are In the Days of Job and Sentence — 1953.

I’ll render it ‘Sentence,’ though it could just as easily be ‘penalty’ or ‘decree,’ based on its sometimes by-title of גזר-דין rather than justגזר1 And that’s what the play’s about — the sentence passed on the Israelites to wander in the desert for forty years and that anyone over the age of twenty is condemned to die in the desert, part of the old generation that knew only slavery and which participated in the making of the golden calf.

When the curtain rises, there are only three left from that rescued, but still doomed generation: Hefer, Iscah and Yemiel.

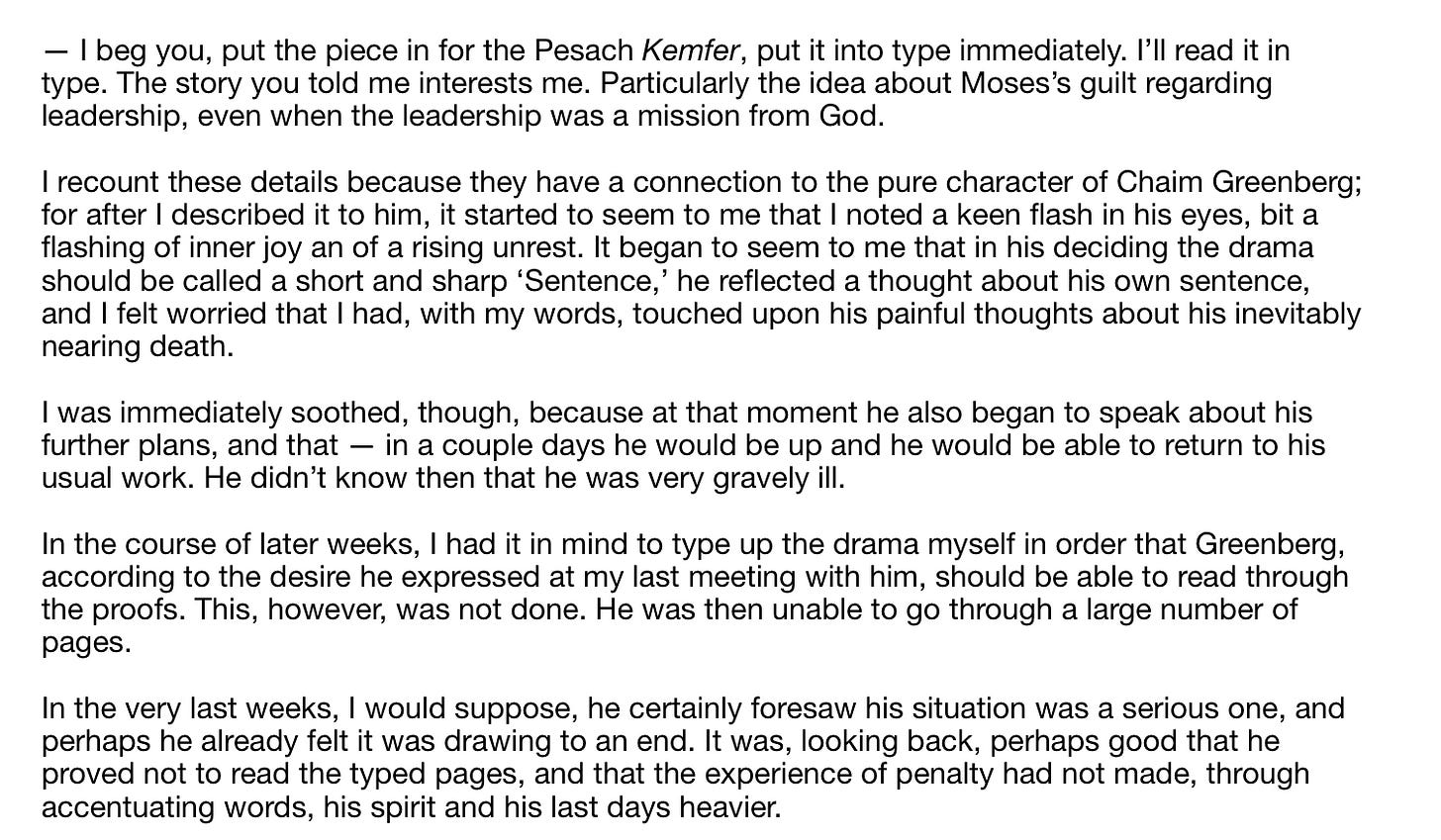

This isn’t the first time that Leivick’s worked through the theme of standing at Sinai, wandering in the desert and whether or not one enters the promised land. He does it quite extensively in ‘Ballad of the Desert,’ which appears in 1945’s I Was Not in Treblinka.2

‘Ballad of the Desert’ is a far more interesting piece to me in some respects than Sentence, a rather straightforward Biblical drama, could ever be. Rather that just retelling the story of the exodus from Egypt and absolutely nothing like a real ballad at all, ‘Ballad of the Desert,’ imagines Leivick himself, his parents and his childhood melamed3 taking part in it — all of his hometown come to stand at the foot of Sinai. 4 And, once again, he employs scriptural basis for this, with a Midrash stating that every Jew, whether born yet or not, stood at Sinai.

From H. Leivick, ‘Ballad of the Desert,’ I Was Not in Treblinka, 1945

And it is by touching the fire of Sinai in ‘Ballad of the Desert’ that young Levi is marked, because God is in the fire.5 He’ll be the only one to walk away from the desert, from the rows of graves he has dug in the sand. And he’s also the only witness — though distracted by the vision of the promised land atop Mount Nebo — to the death of Moses. This version of Leivick walks onward into the modern era, through Hitler, to the resurrection of the dead at the end of the world where he is finally reunited with his parents.

Sentence lacks the more fantastical elements and autobiographical insertions of ‘Ballad’ — and shows no real desire to shift events, invert them or find room within a scriptural source to move the subject matter in a different direction (such as in Akeydah or In The Days of Job). But that isn’t to say that it’s boring or that the material lacks Leivick’s imprimatur. Some passages of it are just as stunningly beautiful as I’d expect from a writer who says that every poem is a sort of prayer constructed on the fly.6

And it’s also interesting to me in that I know a bit more about how it came to be published where it was, in Yiddisher Kemfer7 than usual. Leivick himself tells the story in an essay in memory of Yiddisher Kemfer editor Chaim Greenberg:

This and following excerpt from H. Leivick, Essays and Speeches, 1963.

The second drama he mentions having finished, I think, must be In the Days of Job. Greenberg himself was seriously ill and would die without reading the drama. But it did, in fact, run in the Pesach issue of Kemfer.

Leivick also gives us a summary of the drama itself in the essay. Though it’s an oddly skewed plot summary, as Moses himself only turns up in the last few pages, his confounding absence at such an important time being one of the major plot points.

But in this summary, you can start to see the distinctly Leivickian approach to the theme: The concern with being responsible for others, the guilt of not having saved everyone, the constant survivor’s refrain of ‘why (not) me.’

Most of Sentence’s cast of characters is drawn straight from the Tanakh: Two of the daughters of Zelophehad, two sons of Korach, Joshua Ben Nun…and there’s plenty of action taken directly from scripture going on the the background, mostly offstage. The daughters of Zelophehad, for instance, prevail in their case for inheritance as women rather than men. A last battle is fought before the tribes can go to the river and cross.

But it’s with our three holdouts, not mentioned in scriptural sources, and how they reconcile themselves to their fate, that we spend most of our time. Hefer, the eldest, is over a hundred — and is the man whom Moses spared from death by killing an Egyptian overseer. Iscah, the next oldest, is adoptive grandmother to the children of the tribes. And Yemiel, once a great hero in battle, has the distinct misfortune of being a single year too old to cross the Jordan into Canaan.

I think it’s worthwhile to look at each of their individual dramas, microcosms of the larger drama of the end of wandering which plays out around them; Hefner’s tent, almost the sole setting, just one at the edge of a great encampment of many.

To be Continued…

This is slightly amusing with a knowledge of Hebrew, because גזר also means ‘carrot.’ My Hebrew is appalling. More on this later.

Its first full publication was in volume five of Leivick and Opatoshu’s Zamlbikher in 1943.

Shimon-Leyb! I always like a good Shimon-Leyb sighting. Poor Shimon-Leyb gets zapped.

There is a simply gorgeous bit of symmetry with an essay of Leivick’s where he writes about the mountain of snow that stood in the courtyard where he lived as a child, which the children called…Mount Sinai. All of Ihumen goes to a Sinai of fire, and a Sinai of ice went to Ihumen.

Here, as I’ve said before, I think he puts himself in direct counterpoint to his sister who was burned and died. He is the child who is touched by fire and lives. Something which carries extra weight in the war years.

I find that there’s a lot of words devoted to the brutality and horror of so many of Leivick’s images, with far less given over to the quiet moments and the beauty. Madison’s Yiddish Literature redresses some of this, pointing out Leivick late, more placid poetry about the natural world. But there are always very beautiful moments to be found. Charney sees this more optimistic, borderline humorous in his opinion, Leivick emerging in ‘Ballad of the Desert.’

Unlike In the Days of Job, which was published as a rather nice hardbound book, Sentence was only published in journal form.