The Redemption Comedy, Part 2

The Prophets

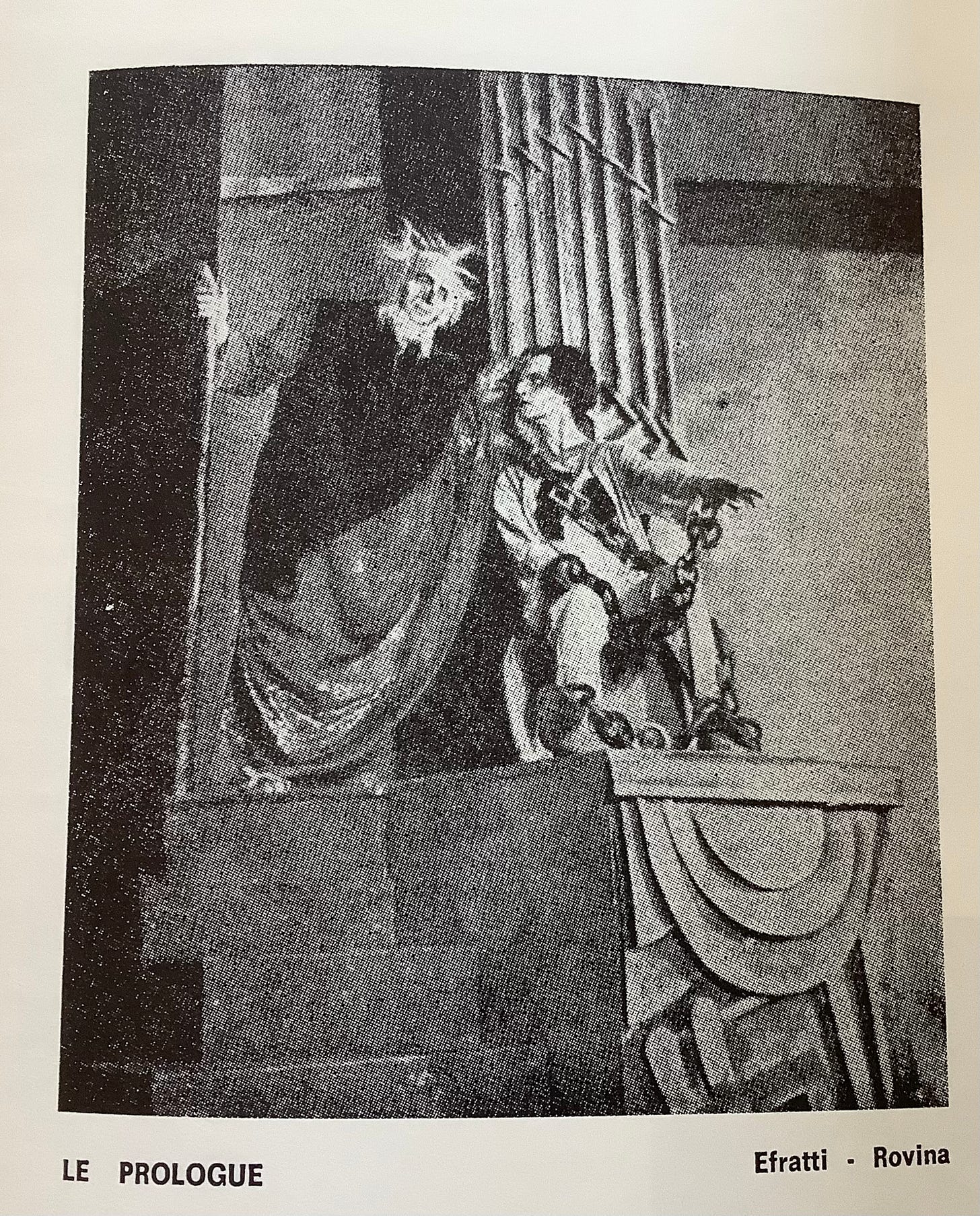

From H. Leivick, poète yiddish, Gopa, 1967. Elijah and Hanna Rovina as the Moshiach in Habima’s Golem

Following upon Leivick’s very pared-back synopsis last time — his own conception of what the play is actually about — let’s look at the Golem’s place in all this.

You might have noticed that the Golem scarcely figures at all in Leivick’s summary from his diary entry from 1932, despite the play being a direct sequel to Der Goylem and his appearing in a least one version of the title. That alternate title, The Golem Dreams, is as good a place to start as any. This is the name under which it got what seems to have been its only production, in Hebrew, by Habima.1

The Golem, of course, didn’t really die at the end of the first play. Not permanently, anyhow. Though it’s impossible not to be moved by the pathos of his childlike begging there not to die, not to be left alone, a counterpoint to his initial pleas at the beginning of the play to be left alone, not to be brought to life in the first place.

What has happened is that, at the very least, he’s entered back into a liminal state (liminality, either linked to class or personal experience entirely in the real world or between reality and imagination/dream in his more fantasy-adjacent works, is a major theme in Leivick) and remains there, in the attic, neither entirely dead nor quite alive, until the beginning of Redemption Comedy. And what does he do while he’s there? He dreams.

What does a Golem dream about? If you’re Leivick’s Golem, you dream about the Moshiach, just like he does. From Leivick’s own introduction to the play:

This and following excerpts, unless noted, from H. Leivick, The Redeption Comedy, 1932.

But first, I’ll take a brief detour into a poem which appears in a cycle near the end of 1923’s In Keynem’s Land, which dates it to roughly the same period of composition as the first play.2

From H. Leivick, In Keynems Land, 1923.

And it’s there that we leave a mute, paralysed, Golem until the beginning of the sequel, hundreds of years later, where he lies covered in shemot — parchments with the holy name — in the attic of a descendant of his creator.

At the end of the world.

The war between Gog and Magog is raging outside and the Moshiach Ben Yosef, a group of his supporters, and his mistress, Lilith, are also hiding in Dvorel’s attic:

And thus the battle lines begin to be drawn between the two Moshiachs, Ben Yosef and Ben Dovid, and their followers.3 In the former camp is Lilith, a sort of Lady MacBeth figure, in the latter, Elijah and Dvorel — the embodiment of purity and motherhood.

Between the camps range the ‘Prophet of the Eternal Present,’ Armilus, whose prophetic powers are more than slightly unclear, the Executioner, whose axe is always available to the victor of the hour, and the Golem himself, who still hasn’t quite grown up yet — he’s still a golem, unformed — though he is virtually indistinguishable visually from the Moshiach Ben Dovid, Hanina.

In fact, the Golem awakens from his sleep (or is it truly death and he is the first of the dead to be resurrected at the end of the world? Or does he only become this with his second, willing death in the sequel?) briefly believing himself to be the Moshiach Ben Dovid before he comes to, assumes his own name again.

It’s worth keeping that first moment, thought, and the blurring of boundaries between Moshiach and Golem, in mind — it’s happened before, in the first part, where the Golem is made as an artificial Ben Yosef, there to violently punish those who would endanger the Jews of Prague, while the Maharal chases the true Moshiach away as having come before his time. They need a messiah who can trade blow for blow, spill blood. Not one whose hands must remain clean.

But now, here, at the end of the world, is precisely the right time for all prophets, all messiahs. And so the Golem goes off to find Ben Dovid.

To accompany our two Moshiachs, we have two prophets: Elijah and Armilus, the old and the new.

Elijah is, rather simply, the biblical prophet, the traditional herald of the redemption, and a feature of four of Leivick’s works written in dramatic format: Chains of the Moshiach, Golem, Redemption Comedy and Wedding at Foehrenwald. Here, he appears in an aged, much physically weakened state — he has gone blind — and before the close of the play he will also have his tongue cut out, rendering him mute. Even mute, he still delivers the damning prophecy with which the play ends: that the Moshiach Ben Dovid must kill the Moshiach Ben Yosef with his own hands, perhaps forestalling the redemption eternally in the act.

Armilus is the prophet of the new age. He was not, prior to this, as Leivick points out in his introduction, a prophet at all, but ‘Armilus the Wicked.’ Leivick, of course, doesn’t throw it all out, I don’t believe he can, and continually works within a traditional Jewish framework.

In Armilus’s case, his mother remains…a rock.4

If in the first part of Golem, the Golem can stand at least in part for the Russian Revolution (whether or not Leivick fully intended this, it’s clear from his account his visit to the Soviet Union in 1925 that the Golem was popularly received as such there), then we find a certain kind of related political personality in Leivick’s dramatic conception of Armilus. It’s unclear if he actually is a prophet at all; His mood, his side and even his face is constantly shifting, changing appearances. He may be a prophet, he may only have the talent of being the first to see which way the wind is blowing at any given moment. There is also the possibility that he realises his own prophecy. And he remains such a relevant figure — a very modern sort of trend-forecaster and social-influencer, with his chameleon-like shifts, from 1932!

To be continued…

The poem is revised for its inclusion in 1940’s Ale Verk to make it more clearly, it seems, about the Golem. This isn’t uncommon for Leivick. The poems period to the publication of Ale Verk are reordered, recontextualised, and sometimes omitted from the volume. Other times, we find poems labelled as ‘variation’ and looking between publications in places like Tog and the collected volumes, it’s sometimes possible to find both.

It’s all a bit over my head, but some traditions hold that the Moshiach Ben Joseph will arrive first and purge the sin from the world, preparing the way, leaving the redemption itself to an unsullied Moshiach Ben Dovid. Which is where Leivick’s plot and dramatic conflict come from for this play.

I know!