The Redemption Comedy, Part 3

The Women

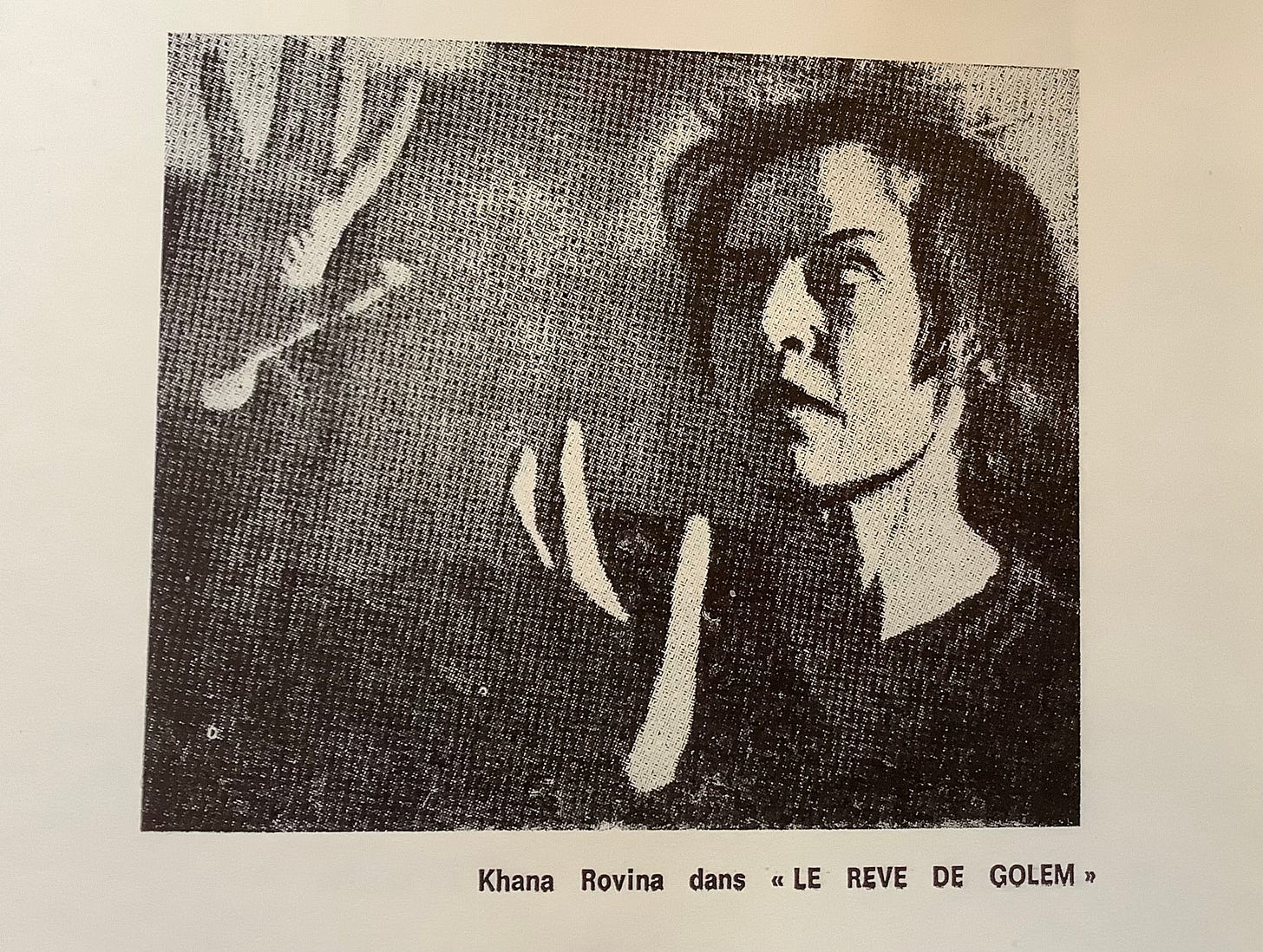

From H. Leivick, poète yiddish, Gopa, 1967.

In Keynems Land (1923), as mentioned earlier, has poems connected to the first Golem play — the Golem makes a full appearance there, in the attic. Leivick’s Golem is a ‘man of the earth’: unrefined, full of rage and physical desire, themes which appear in In Keynems’ Land.

But Lider fun Gan Eyden (1937) also has a deep connection to the second Golem play. S. Charney noted that the poem ‘On the Day of Redemption’ could be coda to it — and indeed it it very similar to the song which closes the play as well as roughly describing the plot of Redemption Comedy — the world rejoices, the redeemer weeps.

Excerpt from ‘On the Day of Redemption,’ H. Leivick, Lider fun Gan Eyden, 1937.

Reading Leivick in conversation with Tabachnick about his composition process, it seems obvious one spurred the other. So absolutely no coincidence there.

Slightly less obvious connections tie this back into a play about being unwell, and coming from the same period as Gan Eyden — Hanina’s commands to the Executioner, behind the gates of the prison, not to ask mirror the ‘this time, don’t ask’ of ‘Open Gates’, the collection’s first poem, and the entrance into a sanatorium that is hospital, prison and monastery at once. And leads us, perhaps, back to the second poem in Lider fun Gan Eyden ‘In Dozing’ — with everyone like the righteous in paradise. The holy feast of the redemption is echoed in the ’Holy Feast,’ in the poem of that name, in the sanatorium dining hall. Everyone who hasn’t died, who isn’t confined to their bed, goes to eat.1

There are also the ideas of inheritance that fill Lider fun Gan Eden: Darwin, spiritual fathers and Leivick’s own concept of his TB being a family inheritance from his grandfather, rather than contracted. Here, in Redemption Comedy, we have at least two major inheritances: a child being born from a literal mixing of blood between the Moshiach Ben Dovid and Dvorel, and Dvorel’s own heritage; her descent from the Maharal.

This is where I’ll shift gears a bit, from the Golem and the Moshiach into Dvorel herself.

In some ways, Redemption Comedy is a play all about different kinds of women and the men they create and nurture rather than just about men and the golems they create. There’s that woman-rock for starters.

Dvorel, the Maharal’s great x^n granddaughter is almost interchangeable, at points, with Leivick’s version of Heloise, from his drama Abelard and Heloise2 — as Levi Shalit points out — she is lover, mother and sister all in one. And Dvorel isn’t just Hanina’s metaphorical mother-wife figure, she is a literal mother who becomes mother to all the children abandoned when everyone goes Moshiach-crazy. Leivick likes mothers a lot and it’s a kind of his dramatic shorthand here. We, the audience, know Dvorel’s on the side of good precisely because she’s a mother and takes on her mothering so willingly.

To contrast, there’s Lilith. Not that Lilith, but the name reveals exactly what she is: an anti-mother. Dvorel’s opposite number in every respect. She can’t stand good, cannot even bear to hear Hanina’s, the Moshiach Ben Dovid’s, name spoken.

And there’s that rock — in one of the most spectacularly weird passages of the play, Elijah and Hanina are hiding out in a crevasse/cavern in this giant, woman-shaped rock which spawned Armilus. And it comes on to Hanina, too, offering to bear him a child.

The idea of the partner is one which keeps cropping up — Heloise, who takes her share of punishment/suffering, Dvorel, etc. Whether a person who ‘completes’ you, forms you or the whole person which helps to hang together another person’s fragmented self. The women, it seems, are often a bit better at ‘wholeness’ than the men. They’re all things at all times. The good ones, anyhow. They often provide that missing piece in Leivick — allow for the tikkun to be accomplished, the repair. A fairly important theme for an author who own self is often divided or fragmented.3

While Dvorel does seem to be pregnant by the end of the play (mystically, by exchange of blood)4 she’s also very explicitly already a mother beforehand and widowed — she’s no Virgin Mary analogue — which is also explicit in the first play, where the Moshiach, Jesus and the Golem have a scene together. They weren’t to be mistaken for each other. Not then, anyhow.

But in Redemption Comedy, the Golem is now indistinguishable from the Moshiach. And that’s how the play resolves itself: the true Moshiach goes off, presumably to his self-ordered execution, and his place is taken by the Golem. Or, perhaps, as Leivick posits, the executioner will refuse, this will be the end, the redemption. That depends on us, the audience.

There’s something troubling in the Golem wearing the same face as the Moshiach.5 You can see the Golem of Redemption Comedy is a better golem/person— he can eventually swear off his anger and his lust in the name of a purer love. But it leaves us with the same problem of the knock-off saviour as the first Golem play —do we await, once more, a real one? A whole one? Hanina has shed blood and is no longer pure. Yosele has the physical, but perhaps not the spiritual substance.

Yet.

I mentioned in the second part of this series that Yosele willingly lays down his life and ‘dies’ when Hanina is arrested by Ben Yosef. Does this self-sacrifice, without spilling blood, make him worthy of being the true Moshiach?

Yosele’s ultimately the key to the liminal nature of the whole thing; The Golem Dreams, after all — everything which occurs might be all a dream, nothing more. But the dream of the Moshiach is the important thing, at least according to Leivick, and how it is that we occupy ourselves until then.

The Golem — like all of us silly, powerful creatures made of clay — has to be better now. Must rise to the occasion.

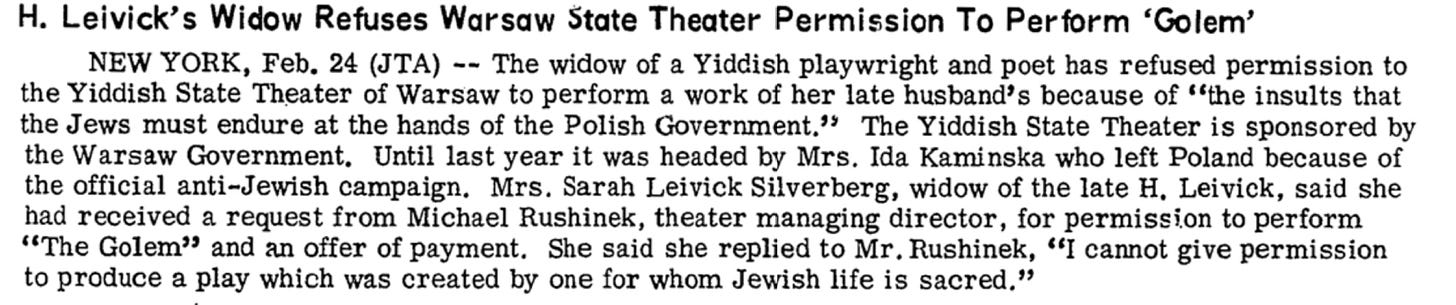

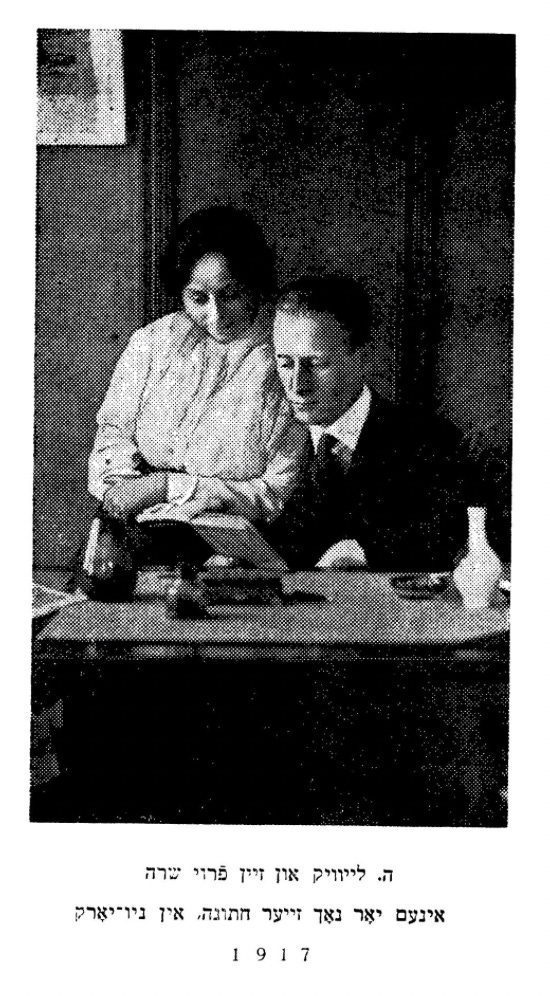

One last below the line note: I mentioned back in Part One that I think Leivick was both the Maharal and the Golem to an extent, both the creator and the embodied rage. But what of the women? I cannot help but see a strange symmetry in the Golem’s being left behind for Dvorel and Der Goylem’s being left to Soreh Leivick as a legacy. And what does she do with it? Uses it to fight back against anti-semitism, of course.6 As one does with the Golem of Prague.

From the JTA, 1969

A lot of the treatment at places like the JCRS — which was a charity institution and took no payment from patients — was focused on feeding the patients and keeping the weight on them.

Slightly later than Redemption Comedy, but the proximity of the two plays and the appearance of Abelard and Heloise poems in Lider fun Gan Eyden does warrant their comparison, as well. Don’t worry, I’ll get to them shortly.

One of the major exceptions to this is Shop’s Raye, who is tossed about by the factions and people around her and eventually bullied into committing suicide.

In the sole production of the play by Habima, Hanina was played by Hanna Rovina — which puts an interesting twist on it all. Not actually in the stage directions and likely because Rovina played the Moshiach in Golem, too. But I have noted elsewhere that there is a prudishness or aversion to physical intercourse in some of Leivick’s dramas, particularly in Abelard and Heloise, which explains a little bit about things.

Leivick certainly has a thing for doubles — alter egos, other selves, fragments of a whole. This is just another example.

I know I come back to this all the time, but I really do love it. I know next to nothing about Soreh, not having access to letters and such, but she intrigues me. I know that their older son, Daniel, wrote to someone from the Forverts about how essential she was to Leivick’s career and have a bit about her from Melekh Ravitch, and I would love to know even more.