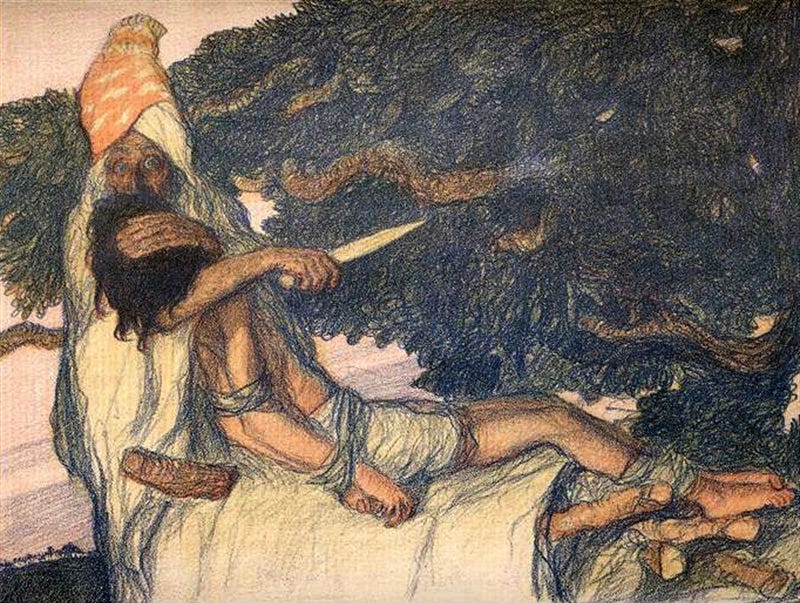

Akedah, lithograph by Abel Pann, Library at the Herbert D. Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies, University of Pennsylvania. If I may be allowed to digress into visual art for a moment, the resemblance of this picture to Ilya Repin’s painting of Ivan the Terrible is striking.

If I hadn’t known that 1933’s Akeydah was written during Leivick’s stay at the JCRS sanatorium in Denver, Colorado —

or, at least, completed there — and only received full confirmation of the fact upon reaching the end, I’m fairly certain that I could have guessed it.

The sequel to Golem, The Redemption Comedy (also known as The Golem Dreams), was likewise at least partially a product of Denver Sanatorium.1 As was the first full book of Leivick’s poetry I read, Lider fun Gan Eyden (1937). There certainly seems to be something about the atmosphere there, as well as the circumstances of how Leivick came to be there, which marks them so indelibly. Beyond, of course, the sheer productivity of a period where there wasn’t much to do but write.

The paradox of the experience rises palpably from the pages for me: finally time enough and solitude to write, not just at night after a long day of physical labour. A more ‘authentic’ artistic life. Almost, putting together the images that Leivick conjures across his plays, poetry and letters to others, becoming a monk whose religion is pure art. But also seriously unwell, wondering if you’ll be one of the ones who gets to board the train back home to New York, back to a life in the world — we have to remember that Leivick does nod his head to the sanatorium also being prison.

The Akeydah itself is, of course, perhaps the most central image to all of Leivick’s work. I’ve touched upon it before, in reference to Leivick’s play dealing partly with the aftermath of the Akeydah, In the Days of Job.2 And Leivick himself explains why the Akeydah figures so persistently in his description of his very bad day when he was seven:3

From H. Leivick, ‘The Jew — The Individual,’ a speech delivered In Jerusalem in 1957.

Akeydah was another play, like There, Where Free (1912) which I knew mainly through criticism until recently. In addition to Shmuel Charney’s take in his H. Leivick: 1888-1948 (1951), I also had Jacob Gotlieb’s analysis of the play from H. Leivick: His Poetry and Drama (1939).

Perhaps the most interesting feature of Charney’s analysis is its taking issue with another piece of criticism by Dr A. Mukdoni which takes Leivick to task for not giving an entirely biblically accurate retelling of Isaac’s Akeydah and seemed to want Leivick to cheer up:

[Mukdoni] accused others, as to why they should have made Leivick ‘melancholy,’ while he himself tried to ‘make’ something of our poet. He wants to make of him a cheerful young man. He wants to chain him to his ‘still, clear and smiling works’ not realising that this is as much a sin as agreeing him merely a poet of ‘melancholy problems.’ Dr. A. Mukdoni says to Leivick, like an old-fashioned photographer: ‘Smile!’

Charney goes on to point out that Leivick is neither entirely dark not entirely light, only Leivick, and composed of many parts and aspects.

Leivick as a whole, though, is always questioning the fairness of the world. How is it fair, he asks, throughout his career, that one could be assaulted as a child — by an adult —for being Jew? How was it fair one could be murdered for being a Jew? How was it fair that an old man (to his own mind) could live but not a young man? How could he walk out of a sanatorium into the sun and fresh air and his friend and colleague Raboy, who loved nature, couldn’t?4 How could he get old and grey and walk away from the Soviet Union and Izi Kharik and Moyshe Kulbak couldn’t?5 How was anything at all fair?

And to that end, Leivick sometimes makes what seems an effort to restore the balance of power in his work — for instance, in Miracle in the Ghetto, he gives a character based on another murdered colleague, Israel Shtern, a greater agency — and a couple of grenades to take out a Nazi tank. He gives the tubercular Everyman Nathan Newman a heroic folk ballad in ‘Ballad of Denver Sanatorium.’ And he gives Isaac — and Ishmael— the chance to get both Sarah and Abraham on the altar.

From S. Charney, H. Leivick: 1888-1948, 1951.

It is absolutely as striking as it sounds.

While the play’s Isaac and Ishmael might be slightly warped reflections of each other, as are the play’s divine voice and the character of the Adversary/Prosecutor/Satan, you can also see the double image of Pike’s Peak (which Leivick could, he says, see from the window of his sanatorium room) and Mount Moriah which Leivick creates in the play’s dedication.

This and following excerpts from H. Leivick, ‘Akeydah,’ Tsukunft, 1935.

I don’t leap to this conclusion purely because one mountain might well be another, might inspire the imagination or play the role for the artist just the way an actor might, or a line about a hospital bed, but also because of an essay where Leivick talks about his own trip up Pike’s Peak.

Unfortunately, I don’t have a precise date for this trip, but it concerns his desire to go to the top when offered a day-trip away from the hospital by friends. He is informed that they can go, but might not be able to stay long. And that there is a point beyond which life essentially stops.

Where is Isaac as he lies on that altar but also somewhere liminal between life and death?

It’s not only the introduction or the coincidence of a mountain, though. The two deaths in the play, that of Ishmael’s comrade onstage and Hagar’s death prior to the events of the play, are rather curious in their description. The former dies of lack of food and water, the latter, presumably from some combination of grief and exposure in the desert. But both die on the stones of the desert with blood pouring from their mouths — which is rather more reminiscent of the end of Nathan Newman in his sanatorium bed in ‘Ballad of Denver Sanatorium’ than realistic depiction of anything else.

Their deaths are as arbitrary and senseless as any Leivick has encountered in life. There isn’t anything particularly holy about them. There isn’t even the small scrap of consolation in the play, particularly not for Ishmael, the first and discarded son, that everything was only a test, a mark of chosenness. What, he asks Abraham, does his God want now that Abraham suddenly want for him to come home — another piece of his flesh?

It’s certainly a view that might have its origins in the trauma of being seriously ill. How much more of you and who and what you are can be carved away, taken, with no immediate discernible earthly purpose?6

Just as with Leivick’s fellow patients, friends and colleagues who didn’t walk away, there is no reason to it, no logic. There is no fairness. In some ways, Akeydah is a howl of grief and rage at all the injustices of the world up to that point.

And it’s only 1933.

To be Continued…

Once again, a quick below-the-bar note from me.

I am forever indebted to the willing soul who got these last couple plays for me.

I don’t own the rights to any of the original material. If you do and want it removed, please let me know. All translations and errors are mine unless noted.

Denver, of course, was not the only place Leivick was treated for TB, and he also spent time in other places, such as the Arbeiter Ring sanatorium in Liberty, upstate New York. I tend to mostly avoid my more diaristic impulses, but one of the reasons that Leivick so appeals to me is that he is also in many ways a poet of chronic illness and trying to find some meaning or greater purpose in that. And being left rather ’singed’ in the wake of Covid, Leivick’s become even more of a lifeline for me than he already was. I remain grateful we met.

The two plays, though they deal with the same material and contain a few of the same characters, are discrete works, mostly unrelated to each other. 1953’s In The Days Of Job is not a direct sequel to Akeydah, particularly evident in the treatment of Sarah. Here, Sarah also comes to Moriah, whereas in In the Days of Job, she remains at home, dying upon Isaac’s return.

There was also his foray into amateur dramatics at yeshiva where he played…the sheep. And was slaughtered, fake blood and all.

This essay is really heartbreaking, and talks a bit about being on the other side of being unwell, too. Having been a patient him, Leivick reacts a bit differently and more cautiously.

Some critics pick up on this ‘why not me’ theme as a streak of masochism in Leivick. I personally hesitate call it that, because I don’t think there’s any element of pleasure in the self-torment (either for himself or his characters), rather a religious hoping to be/admiration for the martyr. And I think you get into rather funny territory calling a serious religious conviction masochism.

It’s not so much a question of why one is sick, as Leivick seemed to treat the illness itself as a family inheritance, as per his interview with Y. Pat. An inevitability. It seems, at least to me, a larger interrogation of how and when one is ‘chosen’ to be heir and the ultimate purpose of the chosenness. There’s also a ‘Why not me?’ — Why did he survive? — in Leivick, as well as a ‘what for’. And what happens to the life you led before that? Does it all just go up in smoke? Abraham and Isaac are also part of his ancestry, as far as he’s concerned, and there are still ‘what for’s hovering over that as far as Leivick’s concerned. Is he, perhaps, uncomfortable at being the heir to the Akeydah, to a father who would have sacrificed his own son so willingly? Does he feel shackled to that in some way, doomed to it? It’s worth looking again to the poem ‘Akeydah’ here, from I Was Not In Treblinka (1945), where he proclaims that he is father and son, knife and fire…especially that last bit.