Hello new friends! This is the third instalment of Leivick’s 1937 trip to Mandatory Palestine. I’ve retained his use of ‘Eretz Yisroel’ and generally let Leivick be the guide — as he was originally. To start at the beginning: Part One and Part Two. You may also want to have a look at the series from his trip in 1957.

A Bright and Intimate Day in Tel Aviv

— A Jew comes to Jews — Profound Experiences from the First Moments — Friendship, Brotherhood, Eased Pain — The Production of ‘Chains’ — Meskin’s Chain-dance — The Effect of the Performance and the Receptions in Hebrew and Yiddish — Chemerinsky’s Lovely, Tactful and Gentlemanly Gesture, Which Provoked Wonder in Everyone and Certainly in Me.

We sat on the balcony of the Atlantic Hotel, which rises on one of Tel Aviv’s noisy streets — a party of friends, of writers, Hebrew and Yiddish, of actors. It was pleasant to give and receive greetings. I felt a bit lost at the great warmth and closeness around me.

It was the harmonious mood of a first, desired meeting. And more than that — just like a song:

— A Jew come to Jews.

— A Jew come to Eretz Yisroel.

— A writer come to writers.

Everything reminds me of that sweet feeling in America at receiving a newly-arrived immigrant.

With my brothers from Eretz Yisroel, that feeling is stronger and sweeter still. The eyes of the Israeli residents welcoming a guest glow fervently and say: See what we ourselves have built.

Ourselves— broken stones, lain foundations, erected buildings. And, indeed, with balconies. And, indeed, with beautiful balconies. And if you go out over the city, you’ll see how large it is, how far it has spread. And how beautiful it is. Over three hundred streets. And we’re now planning to build a second part of Tel Aviv. With parks, with planned streets and alleys. Today, if you will, see the harbour we are building and the new electric pylons and the worker’s villages and institutions and the hospitals and the Hisdarut-undertakings of great scale and the schools; and, if you will, travel and see the kibbutzes, the fields and vineyards…Built with our own hands — of course…

The eyes of the Israeli residents disappear from so much smouldering. The heart welcomes it and is deeply affected by it. The heart responds with love whenever the eyes smoulder with quiet, with earnest, modest pride and don’t cross over into annoyance, boasting.

The feeling: A Jew is come to Jews — fills everyone with friendship, with brotherhood.

That intimate, pure, Jewish warmth, whose wellspring is woe, pained suffering, thin, pure, longing of persecution, of incitement, of shame, which catches its breath at rest, in a minute of bliss, which embraces you and uplifts you, and breathes upon you with the breath of the larger world, of human freedom, of purity of soul, of love for all who live and stir. Not the beastly racial-bloodiness, racial-complex, racial-arrogance — this is not ours. This is not land, not language, not culture, not poem and not work. This is nightmare. This is dark madness. And if it is embraced in us — drive it out, rip it out of ourselves quickly!

Be blessed, friendship and brotherhood; be blessed, be eased pain!

Passing the balcony, noise and commotion and talk of passerby, of people strolling. Many wave their hands in our direction: Shalom, shalom.

The balcony becomes still more — filled, festive.

If only, I think, such a state of the spirit continues the entire time that I spend in Eretz Yisroel.

This doesn’t mean that I want it to remain perpetually holiday, celebration. This cannot be and perhaps needs not to be. You often see the truth of life more during the week than during a holiday. And in Eretz Yisroel there will be also sufficient poverty and burdens, quarrels and socialist and nationalist conflicts, to see them and to be in them. But there is one thing would I certainly like to be perpetual: A state of profound understanding, of readiness to delve into the experiences of another, with attention and friendliness, with clear tolerance.

Why am I stressed by such thinking? And why do I turn so often to such thoughts at the most celebratory moments?

Plain and simple:

Around me, as around every Yiddish writer, and above all, around my present journey here, there will wind, and already wind, plenty of gossip and wicked serpents, and the foreignness which has grown between the Yiddish writers and the Hebrew ones took from us the feeling of immediateness. And immediateness is the first condition of creativity, the first step to men’s hearts.

Therefore I underscore with joy the intimacy which was created between me, the guest, and the friends and colleagues who came to demonstrate hospitality.

I desire nothing else, apart from seeing Jewish lives, Jewish people in their entire being. I want to rejoice in their accomplishments and I also want to take in their mistakes, bad points and sin. And I also wish to carry within me a portion of the guilt.

If people had more strength to hold the light of intimacy within them longer, the influence over lives would not fall so often and so easily into hands of the narrow-minded egoist, the miserly bigot and the wicked.

The guests began to bid farewell:

— We’ll see you again soon at the theatre, at the performance of your Chains.

My sister and brother-in-law, who came with me to Tel Aviv from Haifa, also stood to leave. They felt my desire to be alone. Yes, true, I wanted to be alone for a while.

And although I saw annoyance in my sister’s face that the whole day, ever since I had disembarked from the ship, we hadn’t had a single minute’s time to speak closely, and although I myself also strongly desired to speak with her as a brother speaks with a sister — nevertheless, I asked them to leave me by myself until the performance in the theatre.

It could be that I, myself, instinctively put off to later that intimate conversation which both of us wished to have.

Put off, because — thirty one years lie between us. I would know immediately about what and how to speak with that terrified girl on that autumn, post-Sukkos night of gendarmes, but now — —

When I was left alone, I felt a regret in me that I had let my sister leave. Strangely, I felt a longing for her.

I felt lonesome. I felt that I loved her — my sister.

I was tired, but I didn’t go into my room. I went off through the streets of Tel Aviv which were around the hotel, looking behind and making notes not to wander and not to get stranded too far away, because in an hour, they needed to come and take to to the theatre of Habima.

In the streets — hubbub, life, great movement. Youth. Youth. Summery, hot, short dresses. Happy, energetic gestures. Hebrew signs, Hebrew placards. Electric Hebrew names. Extraordinary, but familiar and pleasant. I ought to say: Exotic? No. Extraordinary — yes. A warm wind blows in my face. Everything around me is warm, peaceful and — Bereshit bara Elohim et hashamayim v’et haaretz — why suddenly heaven and earth? Why suddenly a posuk? Why suddenly Chumash? Is everything that I see around me indeed biblical, if I drag a verse out of the Chumash by force and drag it in here? — But why have I never dragged a New York street into the Chumash? — And why are the houses all so white here? Even at night one sees their whiteness. — Do you not know why? Do you not know, then, this comes from the desert? Do you not know, then, the desert is white, the desert is hot, God lives in the desert? —

And see, what is this? A poster, for the performance of Chains, but what is this manner of spelling the name of the author so awkwardly? Chains, by H. Leyvik.1 Why such fear of spelling the name of a Yiddish writer as he spells it in Yiddish? A name is a name. It must not become abased, become crippled. What sort of respect is it? — —

From the streets, I turn away to the shore of the sea. Strong waves storm the shore, which is set further along with hundreds of chairs. Restaurants, cafes, on the Parisian model — under the open sky. Light, sea signals, and noise of pounding waves.

I ridicule myself for my anger over the bad spelling of my name on the Habima placard. Do I not have more to do that to occupy myself with anger over a poster? I lay my anger at the foot of the sea, I cast it, as one strews dried poppyseeds, into the waves, and the waves storm even harder.

— Look, it’s late already, — I say to myself and start to hurry to the hotel.

In the hotel, they indeed already waited for me. I had tarried too long. I apologised. We hurried away to the theatre, to Habima.

Late in the night. The theatre ‘Tai’ is packed.

The Habima troupe perform Chains. They perform strongly, movingly, with trembling and elevation. Prison-howling, rebellion-crying, victim-weeping. Hunger strike and ‘here is my outstretched throat — slaughter’ and ‘there is a moment when a father must lead his only son to the akeydah.’ Must lead-lead. Slaughter, why do you not slaughter? And — the chain-dance.

Meskin dances the chain-dance. Long legs bent and storming, in a fastening of oppressive chains. Meskin stomps, breaking the floor of the stage as with the feet of a hundred prisoners. His knees stab into the space like giant trees, broken in two. The earth would split beneath the dancing of his feet.

My heart almost leaps in me from an inner agitation, a cold shudder runs continuously up and down the length of my back — shuddering and ecstasy.

Ah, God of mine, why do all my limbs wish to spring apart, burst apart, as though blown apart with powder, when I hear the sound of chains, when I see bars and prison locks — still more when I see the smith lift his hammer and let it fall on a prisoner’s leg? ——

Chains — where they ought not ring; bars, locks — where they ought not hang, where they ought not enclose — they ought to be damned!

Oh, prison, prison! — You will not depart from my consciousness. I, myself, do not wish to forget you, nor can I forget you, either. But how long will the shivering across my back last and how long will I see that actual legs are still in actual chains, and they stamp, storming and buckling knees, streaming with their own blood? ———

Damnation and — ecstasy, how does it match up? Hunger, the lash, the killing of men and — art?

Death, prison-beatings and — play?

Meskin’s storming and buckling knees — they will perhaps answer this.

The curtain falls. Good that there is a curtain which falls. Good when actors perform badly.

And better still perhaps — when actors perform shockingly well, breathtakingly.

After the performance, Chemerinsky,2 the chairman of Habima and the one to whom credit is due for the direction of Chains, held a short reception. He spoke warmly and festively. He spoke in Hebrew and, at the end, changed over into Yiddish and ended his speech in Yiddish.

On everyone, certainly on me, Chemerinsky’s lovely, tactful and gentlemanly gesture of ending his speech in Yiddish made a pleasant impression. It is, by the way, they said to me, the first time such a thing has happened, and one can surmise from this that the official attitude toward Yiddish in Eretz Yisroel has changed for the good, and still more can one surmise from this that Hebrew now feels secure and embedded, and no longer needs to be hysterical and full of fear concerning Yiddish, and that it neared the time of linguistic-tolerance, of linguistic-brotherhood.

There was not one amongst the larger public who might, on a whim, express displeasure in the manner of Chemerinsky’s conduct. On the contrary, everyone, of however many I was able to note around me, showed joy and thankfulness to Chemerinsky for his tact and cultural weight.

Because it was truly a cultured act. In the years-long backlog of suspicions, war and misunderstandings between Yiddish and Hebrew, whether in Eretz Yisroel where Hebrew displayed perpetual, hateful fear and officials prohibit against Yiddish journalism, as well as in all other lands, where Yiddish and Hebrew have established between them relationships of contempt, one courageous and tactful gesture can sometimes work invigoratingly and creatively, as a fresh rain shower on parched earth.

One of the public, not far from the place where I sat, said:

‘I wish him well.’

‘Why shouldn’t it go well for him?’ said a second neighbour nearby. ‘Who does he need fear? Eretz Yisroel loves Yiddish, too.’

In truth, only the cowards who weren’t secure in correctness of their actions and uncultured, arrogant people were able to see in Chemerinsky’s switching over into Yiddish a betrayal against Hebrew and a desecration, goodness gracious, of the holiness of the Habima stage, and make of it a Kasrilevka3 incitement, as the sage HaBoker did a few days afterward (about this later).

At that moment, who was able to think at all about provocation and ugliness of words? Who was able then to think about desecration at all, and more particularly, that Yiddish is a desecration?

You would need to have a dark mind for that.

That moment, though, was light and up-lifting. Everyone’s hearts were bright, white and simple.

They called me onto the stage, so that I might say something.

I, naturally, did the will of the crowd and, still more — my own will, because my heart was full and wanted to share itself with everyone.

There would have been place here, I reckon, to present extracts of my speech, but as in that speech I touched upon certain passing moments which I, in further days, more clearly elucidated at gatherings with the Hisdarut, the Poale committee, Hebrew PEN club and the Yiddish literary union, it will be better, I reckon, not to repeat myself too much, to give the characteristics of the later speeches, particularly the speeches at the Hisdarut and Hebrew PEN club. Here I wish to hand over to the speeches, because they will help me explain myself to the reader. Through them, the reader will also receive a better concept about my approach to Eretz Yisroel and why I travelled there.

And this is the purpose of my present articles. Not only to depict to certain aspects of Eretz Yisroel. This has already been done for me by others, and better.

H. Leivick, Tog, 12 December, 1937

You can see a bit of Leivick’s Chains, in Hebrew, as performed at a later date by Habima here. I’ve had a wee look at Chains before and it’s definitely one of my favourites, particularly because I’ve got Leivick’s account of seeing it.

On to Part Four.

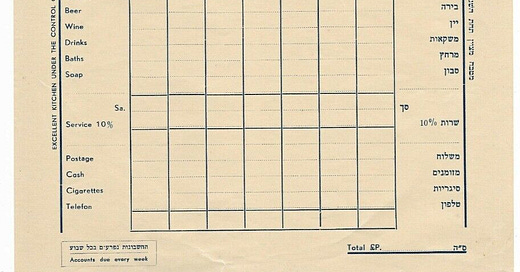

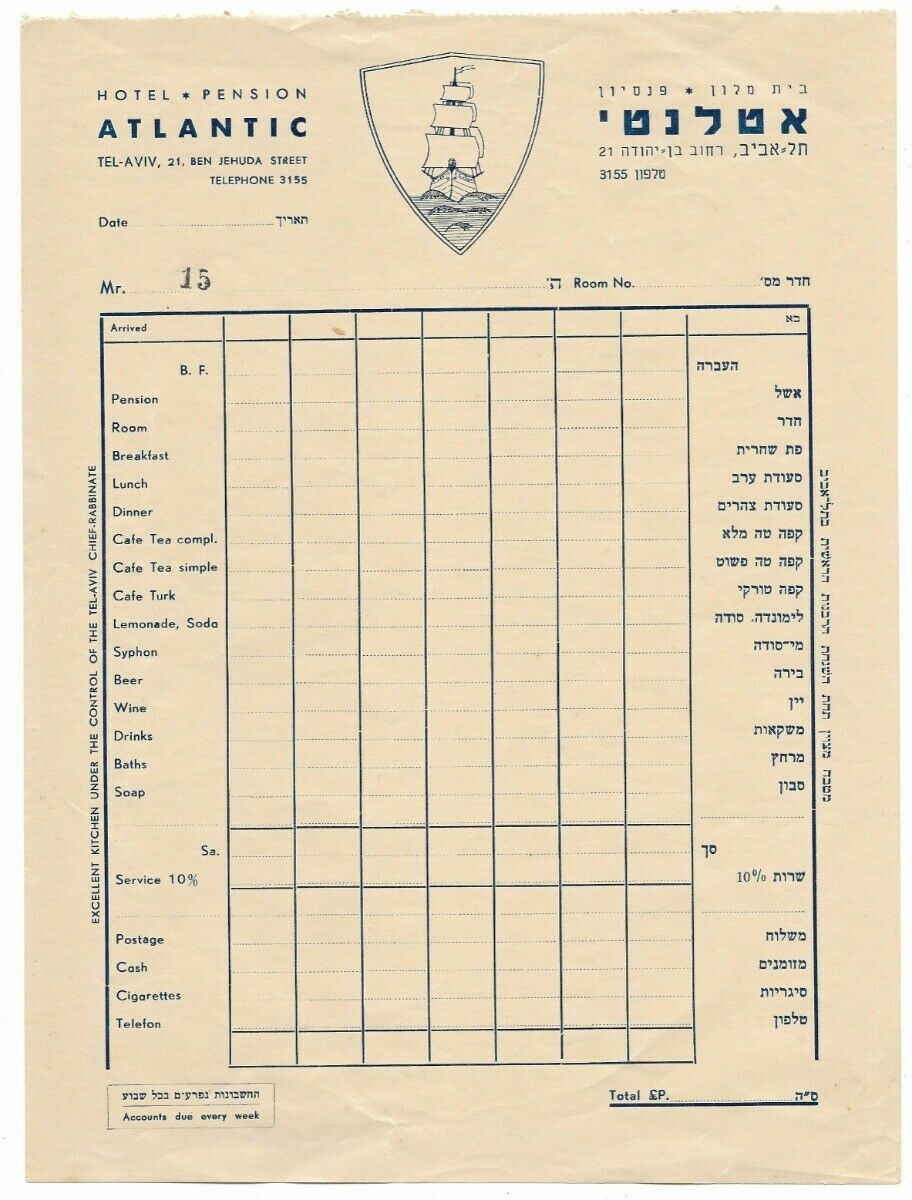

A bill from the Atlantic Hotel, where Leivick stayed. It was destroyed in the 1948 Ben Yehuda Street Bombing.

I hope you will indulge me a bit here. I use the spelling ‘Leivick’ because it’s what he seemed to largely use in English and what the family used going forward. But this is also a correct transliteration — in Yiddish v Hebrew, it’s לייוויק v ליויק, which you find in Hebrew newspapers, posters, etc. Correct, but also not, in a manner of speaking.

Baruch Chemerinsky. Leivick had a long and fruitful series of collaborations with Habima, in Hebrew.

One Sholem Aleichem’s fictional towns, along with Yehupetz and Boiberik. A little town full of little people. Leivick’s use is definitely on the more derogatory side, with no affection — more a town full of the small and small-minded.