I vastly enjoy Leivick’s serialised accounts of his trips to Mandatory Palestine/Israel (1937, 1950 and 1957). So I’m going to do something different and re-serialise the articles from Tog which he published about his third and final trip, which have not, I believe, been collected elsewhere after their initial publication.

Anticipation Which Must Become Reality

I left writing about my recent trip to Israel — until I was on the boat from Israel. Leaving Israel, I would immerse myself in experiences that a Jew feels traveling there and spending time there. Only writing the return at the end.1

Why such a method? To quieten a bit the uproar of the remonstration within me: Why am I going back?

True, I initially returned to Israel only for a short time — in order to take part in the ideological conference which took place in Jerusalem between the 8th and 16th of August. Is that why there had to be an uproar of remonstration to myself, of scolding: It means that you leave Israel and travel back to America?

Insofar as the previously made programme and plan are concerned, there is indeed no ground for argument with oneself. But — you see, though, they’re in you, the arguments. They’re there. And they are demanding. You can’t quiet them — not by logic, not by accounting, and not with the ordinary routine of your more than forty years of life in America; accounting of family, accounting of presence in America, accounting of literature, of Yiddish literature in America: What does that mean? What of it? Will you go and abandon it all and leave? The number of Yiddish writers in America dwindles — will you go and make the number smaller still?

Yes. Yes. Correct. Everything is correct. But what can I do when I sit on a deck chair on the ship ‘Israel,’ which takes my wife and I from Haifa back to New York, and it doesn’t cease to bore into my heart and brain: Why are you going back? Why are you leaving Israel?

True, I try to still this nagging with my answer that I’m not leaving, that although I return New York, I am not sailing away from Israel. Israel is now, through my third time being there, more sharply and more profoundly, truly physically, bodily, in my being more than ever before, and I travel back to New York with the idea of returning to Israel at the first possibility. The thought calms me a bit. But indeed, only a bit. Because — I am plagued by ‘back to New York.’ It places all my Jewish existence as if on the blade of a knife.

The entirety of Jewish fate rises before me in its full complexity. Eretz Yisroel and Exile. Thousands of years of wandering and — Jews had their own land, Eretz Yisroel. Thousands of years of wandering and — Jews, in the span of those thousands of years, yearned with the longing of a great love and of a great belief of returning to the land of their adoration. Thousands of years of wandering and — now Jews had their land back, their Eretz Yisroel. They build the land and the land grows in light and beauty, in tragedy and self-sacrifice and — you’re sailing back to America. And only you alone, then? — Not all Jews go to Israel to be with and in Israel. And those of them who do go — they go as visitors and then go back to America. Just as you, yourself, are doing now.

(I will return to this matter later.)

So. Good. In order to lighten my spirits in the meantime, I will occupy myself, better, with gradually setting down — indeed, only gradually — my impressions travelling there, before occupying myself with my travelling back.

I move my chair away from the rest of the chairs on the deck of the ship ‘Israel,’ in order to be alone with myself while writing my notes. With myself and with my quarrels with myself, with my conflicts and with my seeking expression for them through the lines of poems.

I even start to write a poem about myself, that I am ‘returnee,’ that I am even a ‘yoyred.’2 I write and I break off. I will finish it later.

I suddenly become disconcerted. There run past me two boys whose parents sit in deck chairs not far from me, and I hear as one boy says to the other, in ringing Hebrew: ‘No, let’s not go back to Israel,’ —— And he says it with a boastfulness. It pains my ears and even more so — my heart. I remain sitting, dumbstruck. Baffled.

The boys — born and raised in Israel. Their language — Hebrew. How could they come to say such a thing, let alone so harshly?

I start to look at their mother and father. I start, unnoticed, picking up on what their parents are saying.

Their parents are speaking German between themselves. Between themselves and amongst a large group of passengers who are travelling from Israel to America.

They are German Jews who came to Israel after the downfall of Hitler. A portion of them — brought to Israel from the German DP camps. From a Foehrenwald, a Landsberg, a St Ottilien.3 It seems that they have now lived in Israel for over ten years. Settled down in Israel. Had children. Even become wealthy and here’s the proof: They now travel to America first class. They are well dressed. Their women — elegantly clothed. Some of them even wear anklets on their feet. Not to speak of the jewellery on their red-nailed fingers and on their throats. And — they speak only German. German, German. And — they get on my nerves with their German.

What do I have against them?

They are leaving Israel. Leaving. Leaving.

Before they left Israel, the men went to Germany to receive reparations — the tragic reparations which the State of Israel had carried out and obtained in order to able to make the going onward with the building of the state easier. The reparations — the sound of the word alone fills the heart with a black misery.4

Ten years ago, these Jews were brought to Israel. Some of them even became rich. To their wealth, they added large sums of reparations money. Now they are leaving, leaving Israel forever. They give up Israel. They sail to America. Many families of this type of Jew have even returned to Germany. They were rescued from Germany, taken to Israel in order for them to become wealthy and go back to Germany!!

The fact that families of this type of Jew go back to Germany thoroughly offends me. I knew of them before. And now, when I hear about them on the ship from conversations with of some of the Jews from here who are leaving Israel for America, it offends me anew. — Still, it’s good, so it seems, that these Jews go to America and not Germany. But their German aggravates me. Why should I deny it? Their attitude had infected their little children, that they should say so assuredly to one another: No, let’s not go back to Israel.

I myself am also traveling back to America from Israel. What sort of right do I have to be appalled at the Jews who sail, as I do, from Israel to America? How am I better than them? What right do I, or any among us, to the shameful name of ‘yoyredim,’ or at least with the scornful name of ‘returnees’?

I do not, indeed, have any right. And if ‘returnee’ — I am also one. Can I apply the name ‘yoyred’ regarding myself as well? No. But regarding them, I can apply it. I don’t do it, though. The boundary between is too fine and too small. And I do not take the right for myself to be judge over them. And it is no misfortune at all that a portion of Jews, strange in their disposition toward Israel, leave Israel with the intent of not returning there. Yes, it’s no misfortune. But is a problematic annoyance. But when they leave for Germany, it is not only an annoyance, but also a disgrace to the nation. Yes. So I think, sitting on the ship ‘Israel,’ which sails away from Israel.

I wish to remove the unease from myself and say to myself: You’ll take up the matter of returning to Germany later. Another time. It’s enough now that you deal with the matter of returning to America.

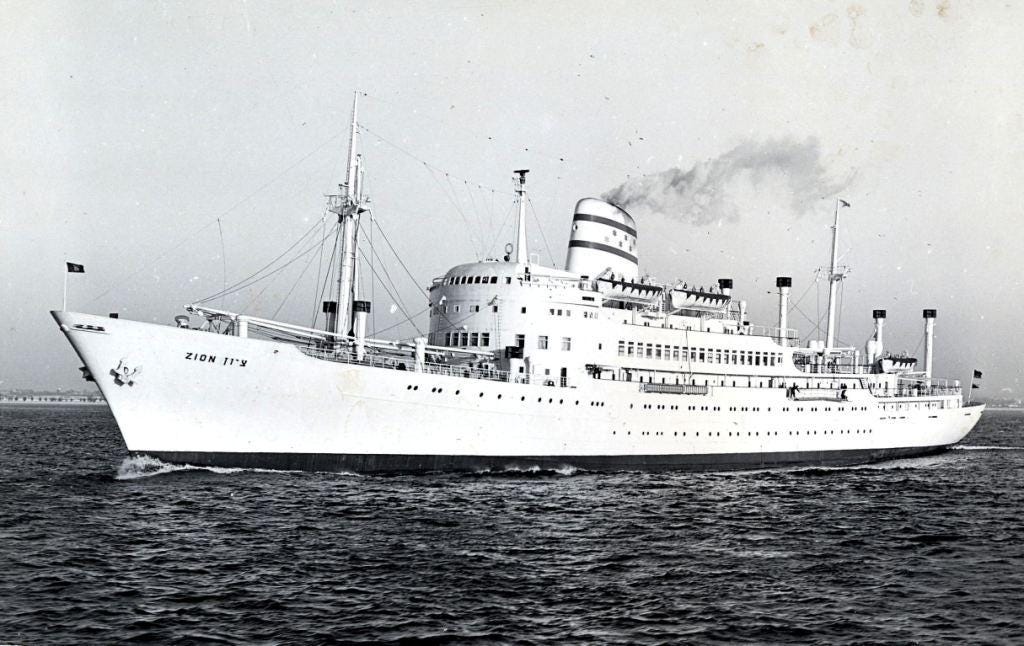

This is also more than enough. Because where does this meditation occur? — On a Jewish ship named ‘Israel.’ Jewish sailor-boys bustle around the ship engines, around the main-sail and stern cables with a skill as though they had been at sea for generations. Jewish ship’s officers and a Jewish captain sail the ship with the same expertise as captains of large, traditional fleets.

The chimney of the ship is massively broad and on it are seven staggered Stars of David in relief. Blue and white colours — the colours of the flag of the State of Israel. And the flag itself, with seven Stars of David is raised high at the front of the ship and flutters in the sea wind. Flutters day and night.

Seven — the symbolic Jewish number.

Seven Stars of David on the Israeli naval jack. Which is no more than nine years old. And it seems to you that it is who knows how many thousands of years old.

How strange that a person adapts themselves and grows accustomed to a situation which has not existed long, only a few years ago. Were someone to have told you there would be such state of affairs in place, you would have met it with disbelief.

Twelve years ago, a young Jewish man lay in a Hitler-camp, twelve years later, he stands by the wheel of a ship from a Jewish state and cuts paths through the Mediterranean and the Atlantic. And now he comes into the dinning room, where there sits a crowd of entirely Jewish passengers, and he sits at the head, dressed in a captain’s uniform, with the whole attitude of a governor at sea, and the crowd rejoices at the captain’s greetings in Hebrew!

I am not overly impressed by a uniform, but I am impressed by the fact, in and of itself, of the change which is no more than a couple years old and which seems to you as if it had never been otherwise. It seems to you that the captain of the ship has already sailed for several thousand years. The captain, in whose hands the entire itinerary of the eternal ship, which is no more than a few years old. Is it not strange? Is it not impressive?

I will, for the meantime, leave aside my emotions on returning, which overwhelm me on the ship ‘Israel,’ sailing from Israel to New York. And I will return, rather, to the beginning, to my emotions of going there on the ship ‘Zion,’ which carried my wife and I from New York to Israel, to Haifa.

Those who depart from Israel look almost guilty. Over everyone’s heads there weighs something like a wariness. Those who travel to Israel look illuminated, hopeful, even excited.

A difference in mood, in the talk, the faces. Different eyes, different movements, different expectations.

Let us go back to the ship ‘Zion,’ which took me to Israel. Let us return to the anticipation which must now become reality.

— H. Leivick, Tog, 9 November, 1957

Onward to Part 2.

The SS Zion of the ZIM line — it was built in Germany as part of German war reparations.

Leivick says elsewhere he likes time to process, sometimes inverting events to create an artificial distance.

One who goes down, ie, leaves Israel. The opposite of making ‘aliyah’ — going up.

All places Leivick himself visited during his tour of the DP camps in the American Zone in 1946.

It’s worth noting that Leivick wrote at some length regarding German reparations and how much a camp tattoo was worth on the market. Needless to say, he was not keen on the idea.