Part One of Leivick’s trip can be found here.

Jews Travel to the State of Israel: On An Israeli Ship

On the Israeli ship ‘Zion’ — direct from New York to Haifa. The journey lasted about fourteen days. The ship stopped for several hours in Gibraltar, the entrance of the Atlantic into the Mediterranean. The second, longer stop — Naples.

A July day. Hot in New York and hot in Israel. One also feels the heat on the ship, but the sea makes it a bit more pleasant. It’s calm — the sea. Sea or ocean, no difference. The watery abysses, the ubiquity of the water, astounds you, captivates you, but also fills you with a sort of fear. The fear crosses over into awe, into a dread. You stand face to face with a power which infects you with a keen awareness of your smallness. You are entirely negated. You cannot look too long upon the endless face of the sea, whether it is calm, quietly reflective, or if it is storming waves. You cannot, though, avoid looking at it for too long either. It calls you, it draws you to itself. More than once, the posuk from Bereshit comes to your mind: V’ruach Elohkim merachephet pnei hamayim.

Someone translated it: And the spirit of God hovered on the face of the waters. Yehoash translated it that way, as well.1 But when I look upon the water, I feel in my senses that one must say: And the breath of God hovered ——— yes, the breath of God. You feel this breath as it carries across the waters, as it makes waves in them, as it makes them foam in white sprays and as it also touches your face. Truly touches you.

We are already deep in the distances of the ocean. The water lies spread out smoothly, and the ship ‘Zion’ calmly slices her path. Serene and certain.

I walk about over the deck and I marvel, not so much at the serenity as at the certainty. From where did it begin — the ship, all its passengers, as well as my wife and I, to fill with this certainty? — I have never, in my life, as a Jew, felt such a full certainty.

I underscore: Certainty. What does full mean? It means entirely forgetting that you are a Jew amongst those before whom you must be careful. It means: Being liberated from being on guard over your Jewish being. From being on guard in case someone, a gentile, treads upon your Jewish being. In case someone forces you to adapt yourself to them. In case someone looks askance at you for not adapting yourself to their language, to their school, to their custom.

And now suddenly — an entirely Jewish ship. The seven stars of David on the flag and on the chimney affect your mood with a tranquility, remove the many burdens from your mood. You suddenly become more personable. You look again at how the flag with seven Stars of David flutters gaily in the sea wind and you begin to flutter together with the flag.

Jews travel to the State of Israel. The first couple days, I don’t yet look at them with any particular attention. I do not investigate them. I do not critique them. I avoid taking a pen, a piece of paper in hand. I drive the writerly yetzer ha-ra2 from me for a couple days — the writerly nature to immediately want to transform everything which you see around and in yourself into material. To record it, describe it, and even, when called for, sing it. Then I cannot even hear someone innocently say to me: Look, how pretty is the sea? Look, how prettily the sun sets! Look, how prettily the moon begins to reveal itself!

For days, I cannot bear words.

And true, it is indeed wondrously beautiful. The person, who comes and says it to me, is correct. He is impressed. He is festively cheerful. He is traveling to Israel. He is traveling to Israel for the first time. He wants to speak to me. He recognised me. He is even a reader of mine. He is acquainted with my poems. He wants to unload his enthusiasm and his happiness for me. That the sea is so serenely beautiful, that the sun dips itself, like a fiery wheel, into the watery horizon, and, especially, his joy that he is traveling to Israel. How, then, can I be terrible and not hear him out?

I listen silently as he talks, as he takes pleasure in his words. He certainly wants for me to agree with him that a sunset at sea is the most beautiful he has ever seen and that travelling to Israel for the first time is a great Jewish happiness. Of course I agree. I nod my head. But not a word comes from my mouth. The man doesn’t misunderstand my silence, God forbid, he senses that my silence, God forbid, is not out of any ill-will. On the contrary — in a moment, he falls silent himself. He remains standing beside me, quietened. We both stand leant against the deck rail of the ship and look dizzily into the water. There, just to be reached with the hand, the sun began to submerge itself entirely into the water. To set. To disappear. And now, above us, there shines a radiant moon. And the water becomes silvery. And the desire for the word silently rises within me. It would be good, I think, to set down the first lines of a poem. The first, white lines, — perhaps like so:

Into the mirror of the sea

I turn my face

When the Western flame

Is set, set. —

I stretch out my hands

To a new rising ———

Perhaps indeed like that?

It would have been just for me to tell it to the man who stood beside me. I didn’t wish, though, to interrupt the solemn stillness of the beginning of night over the endless waters.

The more I look, the more there assails me a terrible and, at the same time, almost childlike question: Where did God get so much water?3

* * *

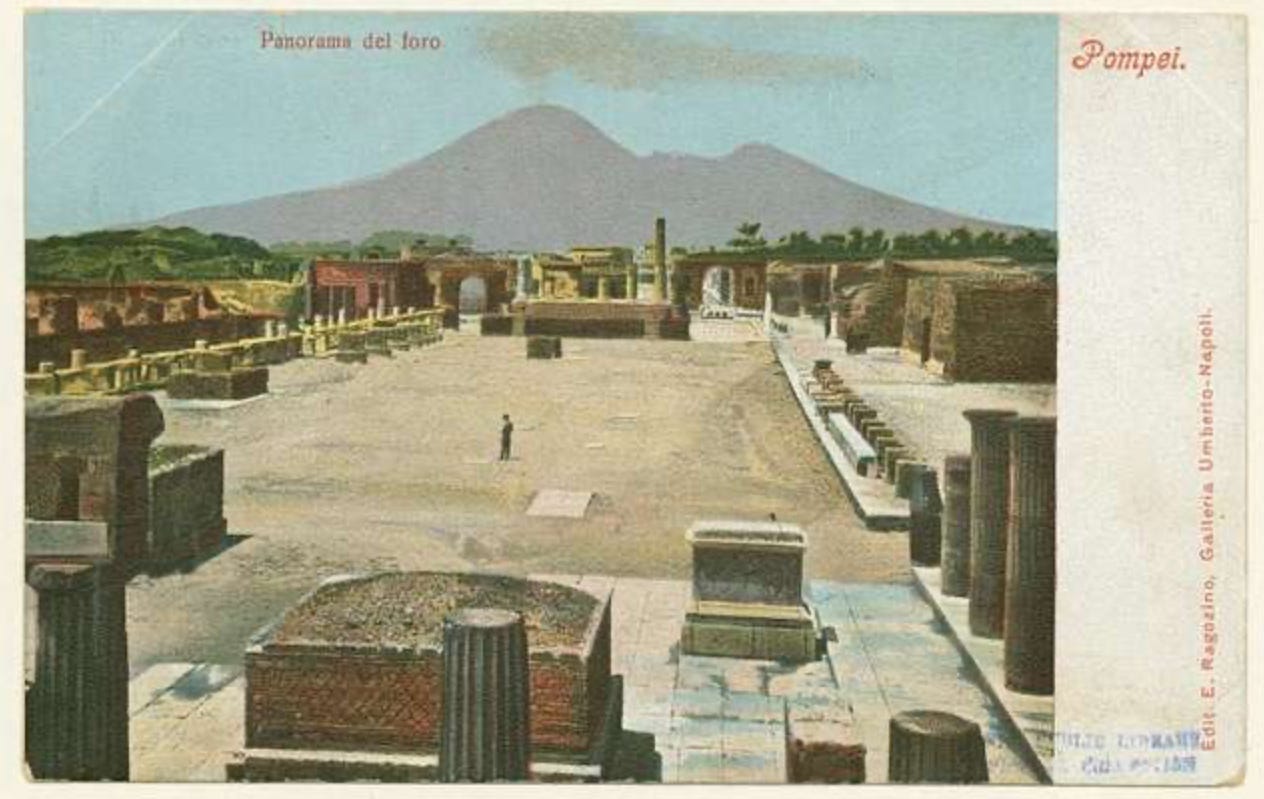

When we sail into the Mediterranean, the mood of all the Jews on the ship ‘Zion’ becomes even more celebratory. This is the sea by whose shore lies our Haifa. It’s almost our own, familiar sea. True, from Gibraltar to Haifa there’s still a full week to sail, and the waters rise from time to time, inundate a bit. You receive a reward, though — you pass by Italy. We stop in Naples. You can use the opportunity to go see the buried town of Pompeii, or travel up to the peak of Vesuvius. You also goes past the volcano Stromboli, which does not cease to give off smoke to this day and at night one can even see the fiery flames fluttering from it.

Most of our passengers are indeed seized by a touristic impulse and want the ship to dock for a day in Naples, starting to hurry in groups to the historic spots with binoculars in hand and camera on shoulder. There is also a similar disturbance in the boat when it sails past an island. They hustle around with such instruments and continually position them — not to lose, God forbid, a single photographic instant.

It turns out that God created these extraordinary things in the world for just this purpose, in order for the tourist to be able to photograph them. And when they finish photographing them, they’re finished with all these things. They have them in boxes and — done. And the city of Pompeii was certainly hidden and then dug back out of its concealment only in order that a passerby might be able to sprint to it and photograph it.

I, on my part, am not wont to bring binoculars or camera with me on a trip. I am free of the touristic eagerness to hastily capture a more ‘factual’ impression.4

The man, my reader, still cannot calm his excitement, coming to me again as I stand by the railing and look down to the nocturnal foaming path the ship cuts for itself in its certain passage over the watery abysses. He turns to me with words which astonish me. He says:

— One doesn’t too often have the thought that Yehuda HaLevi5 traveled from Spain to Israel over the same water, and the sea stormed then and the ship — if you can call it a ship!— was tossed and he, Yehuda HaLevi, sang his songs of longing in the storm; His longing for Zion. Does the thought not also occur to you?

— Yes, — I say, — It does indeed occur to me. And good that you’ve said it aloud so clearly.

— Who knows, — the man continues, — perhaps his ship passed right here, where our current ship travels? Does it change something in our mood when we think about that?

— Yes, — I say, — it alters. And when we say it, we hear as over the water, the great poet’s words of longing resound even now, as fresh as when they first left his mouth.

The man comes closer to me. I see that he wants to say something else, and I desire to hear. He says:

— What do you call this feeling which overwhelms the both of us now in literary language?

— I don’t understand your question, — I say.

— I mean, — he says, — Is it called, say, romanticism or what? And it’s called that in a tone of scorn.

— You worry what it’s called, — I say. — Whatever it’s called, it’s good to think, nevertheless, that more than eight hundred years ago, Yehuda HaLevi traveled over the same water, his heart pining in great Jewish longing.

Afterward, until late in the night, I walk around over the deck and feel particularly at ease with the enveloping darkness and with the thickly erupted stars in the sky.

I walk about and there resounds in me the eternally sorrowful and joyfully enamoured words of lamentation of the great Jew and poet: ‘Zion, do you no longer ask what has become of your captive children?…’

I ask myself: Are these words suitable for your present mood? Here, on a Jewish ship, which sails from New York to Haifa, to a harbour of a Jewish kingdom in the land of Zion?

The sea’s nighttime silence and the silence of the thickly starred sky answer: Yes, it is also appropriate today. They float over the sea’s expanse and they are here. They do not die. This is the wonder of great poetic words which were said in an intimately religious upset and which have, with their full yearning, entered the Jewish heart forever.

* * *

The ship ‘Zion’ nears Haifa. A clear, sunny morning. The wonderful city with its harbour, with its location on Mount Carmel, begins to reveal itself in its full beauty. Now the third time in my life I have experienced this revelation of Haifa, and it seems to me that each time I experience it for the first time (such a sweet unsettling also passes through you each time you approach Jerusalem).

All on the ship are excited. All look intently at the city of Carmel. Most do not stand in one place; they rush around with field glasses and cameras. They truly want to swallow in the revealed beauty. The ship sails slowly and proudly certain into its home port. My wife and I stand by the railing, filled with tension and anticipation. With us — Basya [Charney], the wife of Shmuel [Charney], A”H.6 We look down to the deck below: I suddenly see a group gather around a single man who sits on a ship’s chair with his face turned toward the approaching city and shuckling over over a small book. The man looks rabbi-like, dressed in a long overcoat and worn kapelush. From beneath the kapelush hang curling peyos. He sits, shuckles and says tehilim. With this, he greets Haifa — the harbour city of the State of Israel. The crowd around him — excited people with their cameras. They stand and photograph this rare Jew who does not appear to show any unusual demonstration of enthusiasm but sits quietly, occupied in psalms, and moves his lips pleasantly. He doesn’t even turn his head in the direction of the cameras. It doesn’t concern him. He greets the Jewish Carmel city with a chapter of Tehilim. The photographic tumult around him annoys me. And of he, himself, the tehilim-sayer sitting placidly in long overcoat and kapelush, I am intensely envious.

* * *

Now the ship has sailed into its home port. Now we have the honour of disembarking first from the ship — my wife, Basya [Charney], who travels to a sister, and I. Now we fall into the warm arms of family — my brother and sister, Haifa residents for thirty-five years now — them and their children.7 And now, no less warmly — into the arms of a great number of of Yiddish and Hebrew writers, both from Haifa and specially come from Tel Aviv; representatives from the Hebrew and Yiddish press; representatives from the Jewish Agency and from the Bialik Institute; representatives from the Haifa Va’ad HaPoel and from the city of Haifa itself, headed by its dear mayor, Abba Hushi. In New York, a Yiddish writer isn’t accustomed to such an honour. He cannot even dream of it there. You are surprised by the welcoming joy. Surprised and indeed also a bit disconcerted. I say ‘a bit,’ because in your heart you have expected and awaited this. Why deny it? In New York, you can’t expect such a thing. But in Israel, you do expect it. Israel is different. Why is Israel different? — Don’t ask. You see, though, that it is different. Don’t ask. Give yourself over to the power of that joy. And may the joy and the honour, God forbid, not be light in your eyes. Hold them dear, dear.

Now I see, amongst those who have come to greet us, old familiar colleagues: Sutzkever, Shamri, Eichenrand, Zerubavel, Mendel Singer, Grossman, Borla, S. Meltser, S. Shalom, Rosenhack, Y. Rekhs, and indeed the head of the city himself, a well-known New Yorker who became a Haifa resident — Stending. Only one who always comes to greet me is missing. This is Dovid Pinski. He is at home and cannot come.

H. Leivick, Tog, 16 November, 1957

Onward to Part 3

When Leivick quotes the Tanakh in Yiddish, it’s usually from Yehoash’s translation.

The impulse towards evil.

Leivick, perhaps it should be noted, was not particularly fond of the sea — and writes about, amongst other things, being violently seasick on his way to Argentina for the PEN Conference.

I hope I will be forgiven for being a little silly, but I find this a wonderful convergence and, dare I say it, almost a conversation?

Hebrew poet and philosopher who travelled from Al-Andalus to Jerusalem.

Charney died in 1955. I have previously presented a bit of Leivick’s writing regarding Charney after his death here. I don’t use Charney’s pseudonym unless unavoidable.

Zlata and Herschel, the two youngest of Leivick’s eight siblings. He really only ‘meets’ them for the first time during his trip to Palestine in 1937 — neither was old enough to remember him before his arrest in 1906, though his sister was, according to Leivick, witness.