Hello new friends! I’m not sure how all of you got here, but you’re most welcome.

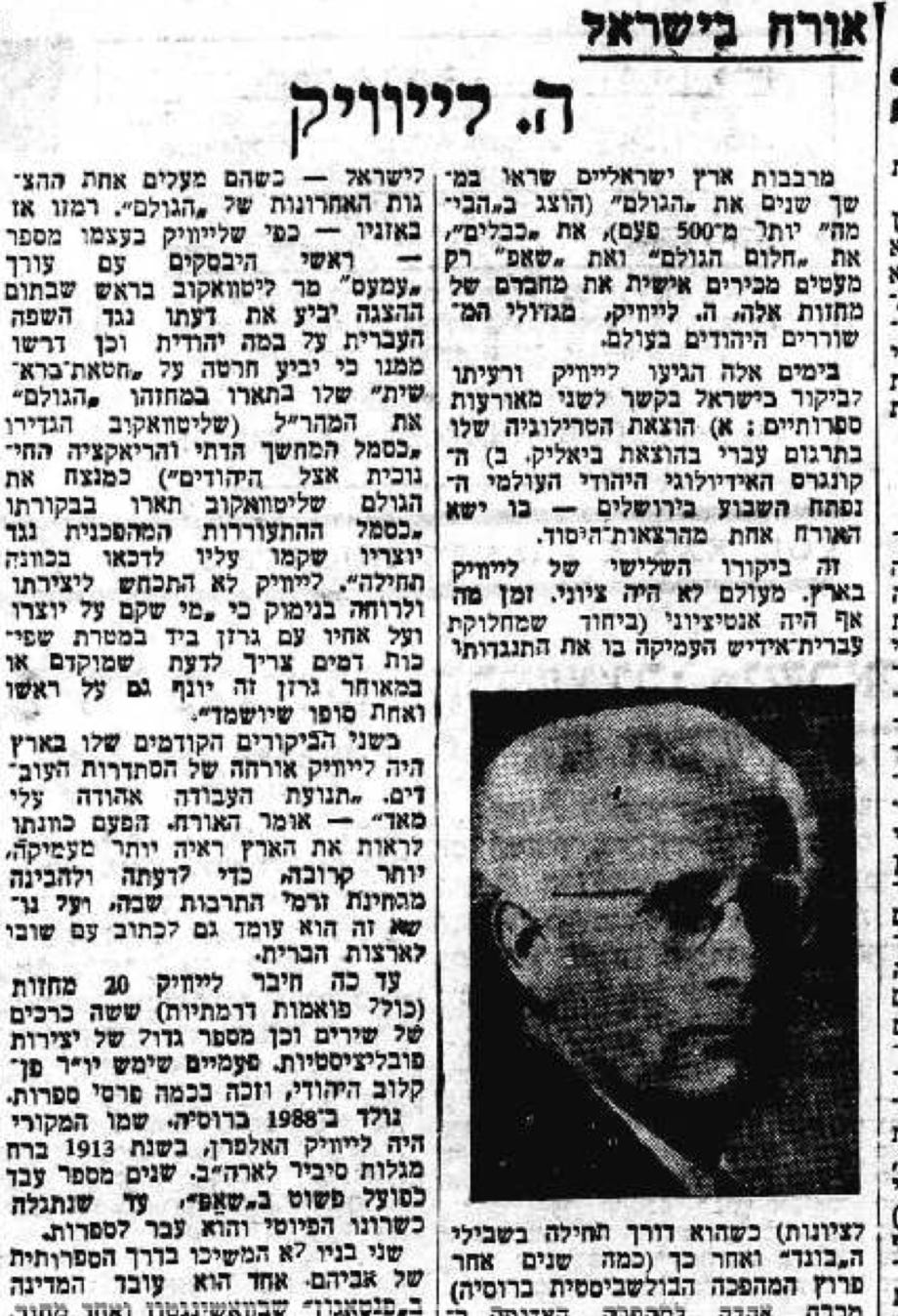

By way of explanation, this is a re-serialisation poet, dramatist and journalist H. Leivick’s articles about his trip to Israel in 1957 for Tog. Translations (and any mistakes ) all my own.

Part 2 can be found here, and the series begins here.

The Idea Conference in Jerusalem: Impressions From My Israel Trip

——— This was my third trip to Eretz Yisroel, which is now the State of Israel. The first time — in 1937, before the state. The second time — in 1950. Whosoever comes for the first time today is astounded when they see an almost already constructed world country. He cannot, though, have the wonderful experience that the one who can compare the present image of the land with an earlier one has; where previously — desert, now — planted, wooded; where previously path over stones, now — paved roads; where previously — dry wastes, now — sown, watered fields; where previously — dark, windy camp-tents, now — communities with houses, as if fallen from the heavens by the thousands; where previously — empty granite and simple stone mountains and hills around Haifa and Jerusalem, now — walled streets, parks, gardens, arising around beautiful national buildings.

Those who were in the State of Israel years earlier and come again now — stand in rapture. All of them rejoices at the accomplishments and building that their eyes see. They must be impressed by the energy which the Jewish person, come from wandering and misery, displays. The Jew of seeming inability to be a person of the soil, a person of hammer and steel — that Jew proves in a short span of time truly wondrously how he mingles the sweat of their face with the sap of the earth — how their heart is mastered by a captivating joy that they are in their home, that they are under their own sky, that they are a Jew at peace, even when they are still not at peace with life and still not at peace person to person.

The situation of the simple, physical life can be, for a portion of the newly arrived, harsh and difficult, the ‘between a man and his friend’ relationships can oftentimes be even harsher and more difficult— but the difficulty and the harshness are deeply upsetting and almost everyone in Israel sets before themselves the mirror of self-reflection. Whether they know it or not — in the entire fashion of a Jew’s life in the State of Israel, there is the perpetual feature of an awareness of responsibility, even when they sin against that responsibility, even when they commit offences against it.

Therefore, it seems to me that the ground of the State of Israel is precisely suited for the holding of Jewish conferences and debates. Although their programs cannot differ than the programs of Jewish gatherings anywhere else — they become permeated, though, through the ground of Israel, with a particular atmosphere, acquire a unique character. They even receive a different hue. The hot sun and the heated unrest of the soul — the dramatic, oftentimes tragic, vigilant worry, with which Israeli life is often filled, gives even ordinary things an importance and sharper colouring. From beneath ordinary words, there burst the tones of quarrel, obstinacy and impatience. From beneath everyday gestures, there often comes an emerging, festive, elation and sometimes a cry of exaltation.

True, more than once that same exaltation falls into words, already said and recited a thousand times, in a flood of speeches two and three hours long. It is also true, though, that even these words said a thousand times are spoken with a zeal which seems as though the heart of the speaker goes up in flames.

This is my impression of a few speakers at the ideological conference. But I get ahead of myself. First, let us outline where the conference happened and how one arrived at it. And very first of all, let us give thought as to why the ideological conference — or, as it was called in Hebrew, HaKinus HaEyoni — was called together. Why was it needed, what did it set out to do, and did it accomplish this or not?

I expect that its most enthusiastic planner and executor, my friend Zalman Shazar,1 one of the representatives of the Jewish Agency, would actually not be able to give a clear, systematically accounted formulation of how such a conference must look even for himself. He had a passionate yearning for a meeting of people — people from the whole of today’s Jewish ideological world — who might, in an intimate closeness, might ponder and immerse themselves in, one under the oversight of another, the critical problems of current Jewish life, of Jewish existence in Israel and in the world outside of Israel. What does the image of our people represent today, having a state and, at the same time, being spread out in great numbers across the entire world? What does the Jew represent, the solitary one, the individual? How do they form their personality, their Jewish consciousness, their sense of Jewish destiny both in Israel and the diaspora? How intensely active today is the Jew’s sense of diaspora? Does their personal life have it’s own formula, it’s own Jewish climate? What sort of path does their creativity take?

Yes, the planner had a yearning for such a meeting of Jewish intellectuals. It was, however, not entirely possible to have a clear imagining of what sort of imagine they would create when they came together and what sort of form they would give their talks and their thoughts. I now think that such a clear imagining perhaps did not initially exist at all. It could not, in truth, exist. It wasn’t able to exist yet, because of the fact that the conference was a first — the first of its kind. An attempt. An experiment, run by many institutions and with many hopes, but also with an internal sense that if only a portion of the hopes succeeded, it would serve. Still more — it would perhaps also be enough even if no particular hope was realised, but for the fact itself that such a coming together of people would be realised. And where? On the soil of Jerusalem.

Incidentally, the name, as it was given in Yiddish, ‘Ideological Conference,’ is not a correct one in my opinion. The name doesn’t agree with the primary intent. The name ought to be ‘Idea Conference’ and not ‘Ideological Conference.’ Ideologies means simply: Decided, concretely-formulated ways of thinking which we disguise in party clothing. When they come to be expressed in mutual meetings, they must immediately cross over into ready-brought, prepared partisan obstinacy. And the intent of such a conference was not squabbling, not stubborn arguments, but quietly contemplative, intimately-delving or, if you will, even confessional statements.

The Hebrew name, ‘Theoretical Conference’ is a correct one. It does agree with the primary intent.

But that name alone still doesn’t reveal, as needs to be, what the essence of the conference is in its taking place, in its realisation.

I say this not as a proclamation, nor as a reproach, but as a designation of its factual character. It happened as it happened, and in the given situation, it likely could not have happened differently, although it did need to happen differently.

I allow myself to present here a couple of brief points from my lecture at the conference — indeed about the character of the conference itself: ‘—— I was greatly moved in my desire to journey to this ideological conference. Great, too, was the anxiety and the hope that I would take part in a stimulating accounting of the soul, which an individual performs on themselves, a sort of vidui2 — while living, in order to live. A sort of self-examination that a person, and above all, today’s Jew, carries out when they are alone with themselves ——in order to then recount before a select group ——— to stand before one’s own summoned group, as one stands before a clean and pure mirror. And each of our gazings should be truthful and bring relief, understanding, as befits intellectual people. ———’

Yes, this aim was not often attained. In the given circumstances, one must accept, it could not have been carried out otherwise. But it can be a lesson and will, be, I hope, for the next conference, that it might not repeat the same lackings. — It should overcome its circumstances and happen differently. It should be thoroughly theoretical, as was the yearning of its instigator and planner.

* * *

Perhaps it is a sin on my part, and that of every friendly critic, not to satisfy myself with the very atmosphere around and over the conference. And in truth, the Jerusalem atmosphere around and over the conference can, if their Jewish hearts are not entirely closed off, fill everyone with joyful exaltation.

In particular— the location where the conference took place. It happened in the just-built, heart-stopping buildings of Jerusalem University, on the mountains and hills which surround the eternal city. Not all of the buildings are finished yet nor are all of the surrounding boulders yet cleared away and flattened out. From the city to the university, you travel via new, smoothly paved winding roads, which reveal for your eyes the surrounding mountainous beauty. The beauty waits for Jewish hands to plant it with woods and flowers, with parks and with festive places. And Jewish hands do it. Approaching the university buildings, you pass through groups of Jewish builders and masons, plasterers and stone-drillers. Hammers pound, wire and cables are lifted, granite stones are broken, tiles are laid. And everything is white, bright and spacious. And the sun burns, midday blazing, breathtakingly.

You pass by the masons and builders and are a bit embarrassed. Rightly so or not — you are a bit ashamed. You think to yourself: They work hard, with the sweat of their bodies, they hammer and hack and drag and clean and you go past, disappear into a hall which they’ve only just built and cleaned, in order to listen to talk and talk yourself.

Hammers and words, granite walls and — speeches. Deed and — verses.

You come into the conference hall, take you place, and the procession of the word begins.

The procession last days, and evenings as well. Jews from America speak. There speak Jews from Argentina, London, Paris. Jews from Israel speak. The government man speaks. The Torah man speaks. The Mapai man speaks. The Mapam man speaks.3 The rabbi speaks. The philosopher speaks. The poet speaks. The Orthodox speak. The Reform speak. The old-timer speaks. The reformer speaks. The slightly late, the prophetic, speak. The up-and-comer speaks. The assured, the oratorical antagonist, speaks. The one who gestures emphatically with their hands speaks. The still, the hunched-over speak. — And you imagine that suddenly, the doors fly wide open and there streams in from outside the entire group of builders and drillers, striking the tables with the sound apparatus, the speaker’s lectern, and shouting: Enough talk! Enough speeches! Be quiet!

Yes, so you suddenly imagine. But this is indeed only a fantasy. In reality, the picture would look entirely different if the builders outside came into the hall in the middle of the speeches. They would certainly stand separate and reserved, and wait to feel themselves as part, as partners, as one whole here on the transformed mountains around Jerusalem, around the new Jewish-built city. Word and hammer. Deed and thought. One whole. Word becomes deed. Deed becomes thought.

Amongst all the speakers, representatives of our current strata and streams, there is lacking — I suddenly realise — an important representative and perhaps the most important: Absent is the representative of our people’s youth, both from the Israeli youth and the Jewish youth of the world. The conference is lacking the voice of the new, young generation — the voice of its present longings: Religious, national, artistic, literary. The voice of its inner seeking, dissatisfaction, quarrelling with their ‘exile’ fathers and grandfathers and also the voice of longing for them.

I look around me. I see: The elderly sit. The elderly speak. The experienced, the heavy-shouldered, the white-haired, the now a bit hoarse and tired. But the voices, both of the Sabra and the American young Jewish men and women, are absent from the building. And it’s a pity they are lacking.

And it is no pity at all that two other voices are not at the conference. It’s good that they aren’t there. They cannot be here and need not be here. Two voices which, although they are as disparate from one another as east and west, and one must say ‘lehavdil,’4 they go together and become one in their poisonous enmity toward the State of Israel and to the entire Jewish community across the world. This is the extreme, fanatical voice of those who sit concealed behind Jerusalem’s hundreds of gates and the traitorous voices of those who sit, to this day, Stalinesque, behind Khrushchev’s hundreds, lurking.

H. Leivick, Tog, 23 November, 1957

Onward to Part 4

Leivick in Ha-Aretz in 1957 — ‘A Guest in Israel’

Writer and poet. Later to be President of Israel.

A sort of last confession of sin — but here, as Leivick says, while living. An unburdening of the soul.

Literally, ‘to separate’ — so that one item is fully distinguished from another, not taking on its characteristics, though mentioned in the same breath.