Part 9 can be found here, and the series begins here.

At Night in a Jerusalem Hospital

Several hours into the night. I lie on my hospital bed, fenced-off from my two sick neighbours, already operated on, by a curtain, and look continually at the glucose container from which there drips into me, through an needle inserted into my hand, drop after drop of sweet water. I do not take my eyes away from the glass wheel where the drops roll down with precise regularity. One by one, one by one. It seems to me as though a curious water-clock stands over me and drips out its seconds.

Behind the curtain lie my two neighbours, and I do not see them. I only hear: The one who lies directly beside me breathes heavily and keeps silent; the second, who lies beside the window, moans continuously. He was still coming out of his anaesthesia this morning and is probably in post-operative pain and cannot contain his moans or doesn’t wish to contain them. Why does it occur to me that he doesn’t wish to hold them in? Because here another lies beside me who has also already awakened and doesn’t let out a hint of a moan. Keeps so stubbornly silent, that it truly begins to disturb me that he remains silent while the other, on the contrary, moans as if with a vengeance.

All the while, the night-sisters come to the two operated-upon neighbours. Care for their conditions. Go in and out. And over me, a young doctor keeps watch. Does not leave my bedside. He stands beside me or sits on a chair in the corner directly opposite my bed, and does not take, like me, his eyes from the container with the dripping droplets. He does not, incidentally, take his eyes from me either. He faithfully watches over my every movement.

What is happening with me is, it seems, clear to the chief doctor, but I still don’t know myself what is going on with me. I only know that I was on the threshold of an operation. Whether I am still on the threshold or already come through the danger — that isn’t clear to me. The doctors, who had a consultation about me two hours ago, do not appear any longer. I must, it seems, take it for a good sign. I try to draw my watch-doctor into conversation. He doesn’t allow it willingly. I draw him in anyway. He speaks very good Yiddish.

— I see that you’re very anxious, — I say, — in your watching over me. Can you not tell me why?

— It seems so to you, my friend, — says the doctor. — I’m making certain the glucose drops drip correctly.

— Is it still possible that I might need to be operated on?

— If the night goes well, it’ll be fine.

— I don’t feel poorly now, — I say.

— That’s good. That’s very good. But if you feel new spasms, you should tell me immediately. Immediately.

— I certainly won’t keep it a secret, — I say.

— If you can joke, it’s certainly good. Judging by your poems, you’re far from being a joker.

— You know my poems? — I say excitedly.

— Why is that such a surprise to you? — says my watch-doctor, — we’re in Israel.

— There are plenty of Jews in Israel who don’t know. Most of your hospital personnel, incidentally, don’t speak Yiddish willingly.

— But I know. If you were to put those who you think don’t know up against the wall, it would prove that they also know —

— Do you mean — me or Yiddish?

— I mean both. You know some of our personnel. Our young women, the hospital sisters — they also learn Yiddish. Do you know from whom? Indeed, through many of the patients.

— You surely know Hebrew, — I say.

— Yes. Of course. I’ve already been here in the country for more than fifteen years. Ordinarily, we all speak Hebrew here, both amongst ourselves and to the sick who understand Hebrew. —

— The hospital, it seems, is overcrowded ——

— You have no idea how overcrowded. Incidentally, you see for yourself — you lie in a threesome in a room where only one patient should lie.

— May I ask who my neighbours are and what their operations were for?

— Of course you may. But I don’t know many details. I only know — the one who lies next to you is a Jew from Morocco. An operation on the heart. The other, if I’m not mistaken, is from Romania. An operation on the lung. He had a lung removed.

— And if I have an operation on my stomach — there’ll be a complete set.

— What do you mean? — my watch-doctor looks at me.

— I mean: It would be a perfect set. Stomach, lungs, heart. A symbolic whole. A symbolic examination. In another hospital, for example, in America, it wouldn’t occur to me. But here, in a Jerusalem hospital, it occurs to me. A Jew from Romania and a Jew from Morocco and a Jew from America — in one little room, and in the neighbouring room it is probably the same: a Jew from Yemen and a Jew from Poland and a Jew from Egypt. They lie and the drops of water drip into them.

— Correct indeed. Interesting indeed, — says my watch-doctor, — but you shouldn’t speak for so long. Particularly not with the rubber tubes in your nose. —

— May I think to myself, though? —

The doctor looks at me a long time, bursts into laughter:

— You can think as much as you like. You can even compose a poem. But it would be better if you tried to sleep.

— With glucose needle in my hand and a tube in my throat?

— Nevertheless, try. You shouldn’t talk any more, though.

The watch-doctor sits on his chair in the corner opposite my bed, sits and watches the glucose drops. I do the same. I don’t know what he thinks, watching the drops, but what I think — I know:

— They cease to be peaceful, regularly falling moments, but they suddenly become rushing, tangled shreds of torn-apart hours. They call to each other with a zealous haste and anger. I would swear that as small as they are, I hear as they strike one another as though with hammers and their angry striking bursts in through the skin of my hand and rushes through all my limbs like uncontrollable waves; they storm in me, like the waves of the sea storm the shores which bound them. I strain my eyes to see if I am mistaken. Yes — I am indeed mistaken: The drops fall quietly, as they must fall. — Good that I did not call out to the watch-doctor to warn him about the storm in the water container. He would have laughed at me, or he would have thought that I was speaking deliriously. It is good indeed that I didn’t call out. But it could be that I have a fever. And perhaps it is just an imagining — from fear. Fear of whom? Fear of what? Perhaps at the thought that I see myself and my two operated-upon neighbours as one interconnected symbol and the symbol catches light over me with a Jewish fire? —— The Jewish body lies in torment lies cut, lies in spasms, lies in Jerusalem; lies and waits for the night to end, for the drops of water to finish dripping, from the storms to still themselves, for dawn to come. ——Why should night stretch out so long? Why? ——

My feverish thoughts are suddenly interrupted by a shout from my Moroccan neighbour. Chot! Chot! — it seems to me he calls. What the call means, I don’t grasp. Right at that moment, two night sisters come hurrying and start to quieten him, softly and kindly.

— What does his call of ‘Chot’ mean? — I ask my watch-doctor.

— This means ‘Sister’ — he explains to me. Achos in Sephardish.1 He swallows the alef, so one only hears ‘Chot.’ He calls, it seems, the hospital sisters.

I hear as the Moroccan patient says to the sisters: ‘Mayim.’ I hear the other patient say the same. The first says it in a low voice. Says it and breaks off. The second accompanies his request with a confused moan.

Suddenly, there carries over the entire floor the howling cries of a child, of a little boy: Mama! — The two sisters run out of the room and hurry away after the child’s crying. It seems that the boy doesn’t lie far from our room, because I hear very clearly as the two sisters begin to gently soothe him. The boy gradually stops crying. Thin sobs still reach me until they become swallowed in the stillness of the night. The night-stillness itself, though, in a hospital, it not an entirely quiet one, particularly when you are awake and you listen to every rustle. The silence itself is full of rustlings.

I uncover a little gap in the curtain which separates me from my neighbours and I look in at them surreptitiously, not moving my head too much. The Moroccan, I see, lies outstretched, like me, on his back. His entire body, up to his neck, is covered with the blanket. His face, too, is covered, only his eyes look out. His head — unusually large, by the size of his head, I estimate that his body under the blanket must also be very large. It seems to me that his eyes are somewhat open, but they look only ahead of him, give no movement to the side. He lies frozen. I want to feel in him whatever connection there is to me and in me — whatever connection there is to him. I cannot decide if I feel it equally.

On the other bed beside him, on the other side, lies the Romanian. I cannot see his face at all, both because of the half-darkness and because the Moroccan obscures him. I do see, though, that he moves his hand. Moving slowly, stretching out his fingers as if he beckons to someone. He lets out a long moan. Becomes still a moment and again — a moan. Doubled. Then tripled, quadrupled.

His moans keep me, naturally, not only from falling asleep but even from dozing. I take them patiently, but also with a bit of disgust. And when I feel the disgust in myself, I start to scold myself for it. ‘Let’s see what sort of hero you’d be if you lay with your lung cut out!’ and ‘How do you come by such a dishonourable feeling as being repulsed by someone’s moaning? Just a minute ago you saw yourself symbolically connected with them, with those operated on. Jewishly intermingled with them. What does Jewish mean? It means: Brothers, it means family. You own fate lies in their pains, in their moans, in their silences. They are yours. Here, under the hospital roof on the earth of Jerusalem.’ ——

‘Yes, yes, for this alone your coming here was necessary and your becoming ill was necessary, in order for you to lie here, with your eyes open and hear how one moans and how one keeps silent. And your open eyes should watch through the whole night as the water from the container drips, drop by drop, drop by drop.’ ——

There started to arise in me the illumination of an extraordinary accounting.

H. Leivick, Tog, 11 January, 1958

Onward to Part 11.

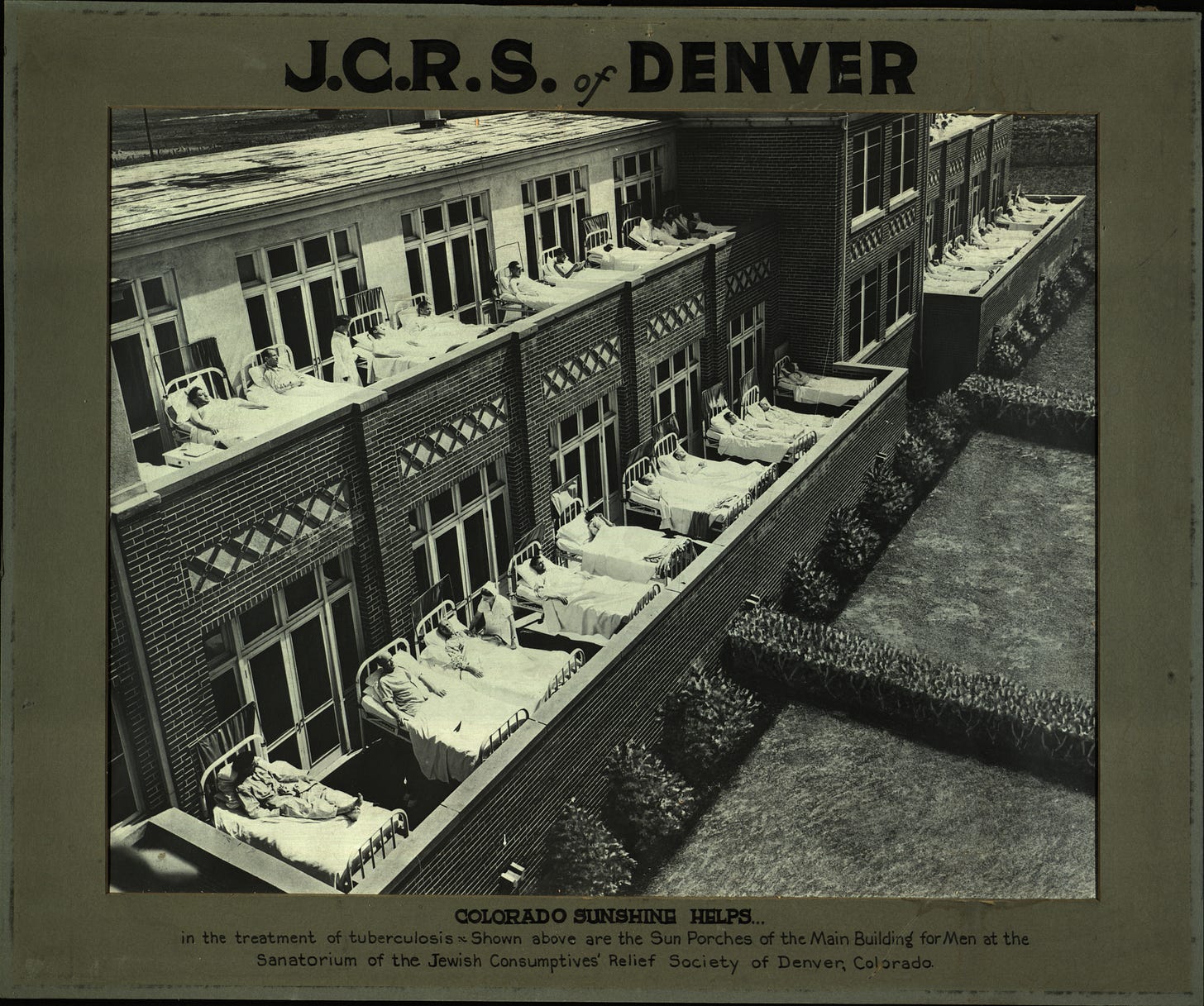

A blast from Leivick’s own past, his treatment for TB at the Jewish Consumptive’s Relief Society (JCRS) sanatorium in Denver, Colorado, in the early thirties. Rather than travelling around Israel this trip, Leivick goes on a journey through time and space while remaining in one place….

Leivick actually started his writing as a teenager in Hebrew. But Ashkenazi Hebrew, which sounds fairly different from what one usually learns or hears outside of a religious setting today. On his trip in 1937, Leivick remarks that ‘ I understand Hebrew, but speak it, I cannot. And when one speaks in Sephardic pronunciation, I catch one word in ten.’