Part 12 can be found here, and the series begins here.

Harsh Words and a Quiet Blessing

On my third day in Ziv Hospital, it becomes clear that I have entirely avoided the danger of an operation. I go into the category of patients who must be in hospital another couple days for full certainty. In a couple days, I will be able to return to the hotel and spend time there, as much as will be necessary, to regain my strength.

I am liberated from the glucose containers and tubes. I can move freely on the bed and friends can come to see me. They indeed come. And my wife, who is beside me almost the entire time, sees to maintaining a certain order. The hours that I remain alone — my wife goes to the hotel to eat and rest and guests do not come during those hours — I lie and think, now measuredly, and even a bit relaxed, to myself about the alarm I caused. Nothing else was truly lacking but to lie in a hospital in Jerusalem instead of travelling around the country and see how the land built itself; to see what has happened in the country since my last visit in 1950. I feel, lying in my small room in Ziv, that outside the hospital walls something big occurs, something is going on there, something happens in an extraordinary manner. I feel that the goings on stream into the room to me through the window, carry across my two neighbours, who also become better from day to day, recovering from their operations. Yes, the examination has happened, and now the becoming well happens. Examinations on an scale of all-Jews.

I am taken again into the x-ray room for definitive precaution. And on the way, in the long corridor, who comes with meet me with a bouquet of flowers in hand? Mrs. Rachel Yanait,1 the wife of our Israeli President. I am both surprised and deeply moved. When the people around recognise her, there is a bit of a ‘disturbance.’ But the ‘disturbance’ is quickly resolved and it becomes a natural event. Simple and human. I shake her hand. I thank her for the honour and the flowers. I confess that I put her hand to my lips. The lady is disconcerted. She gives me a greeting from the president. I must understand that he cannot come. He cannot and must not make exceptions for anyone. But she can and she may, his wife, for herself. Every time that an evening happens for me, she comes. She sits in the first row and shows interest in my talks and readings.

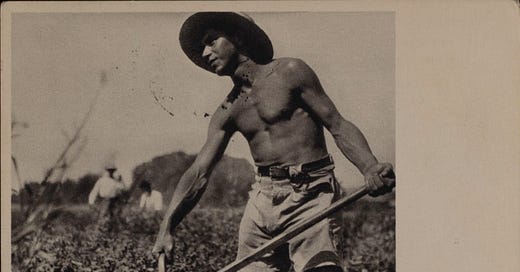

I am brought back to the room. My mood, because of the visit from Rachel Yanait, is uplifted. However simply I should take it — it really isn’t so simple. The people who are now at the head of the Israeli government were, years ago, hard-working builders of the kibbutzes and settlements and of the whole new way of life; they were, and are also now, not divided from the people. They are in the people, in the full simplicity of the people, and in the full, simple formula of the people’s way of life. There is no trace of pride and of being lost in the influx of honour which the people bestow on them. In the influx of honour and — perhaps, I would say, the burden of honour.

Yes, it is certainly simple, such a visit from the President’s wife — a visit to a sick person, to a friend, to a Yiddish poet from America — and yet it truly isn’t simple. It is an act which I want to particularly single out, and I do single it out and my heart rejoices because of it. The hospital room takes on a different appearance, a festive one. If I could speak with my two neighbours, I would tell them about it. But they are still too occupied in the slow process of their becoming well, they still do not rise from their beds too much and I still don’t have a common language with them. I am apart from them. They have, true, sharply tasted the cutting of the knife and I — not. I have escaped it. What am I compared to them and the pain which still dominates them?

At that moment, there enters the young man with the bound, injured hand which an Egyptian bullet struck in the Sinai action. He has already visited me a couple times. Each time, he has looked for the opportunity for a long conversation with me. He is pleasing to me — both in his tall figure and young, handsome and energetic face. Certainly exudes from him and, at the same time, a sort of sorrow. I would even say that a sort of tragedy comes from him. His eyes bear a glimmering keenness in them, but his thin lips are still child-like, as though the mother’s milk isn’t yet off them. He is born in Israel. A Sabra, that is to say. He knows almost no Yiddish at all. His mother-tongue is, naturally, Hebrew. He also speaks English quite well. As it is difficult for me to speak Hebrew, I speak to him in English. He, though, insists that I should speak Yiddish with him and he — English.

— Why do you want for me to speak Yiddish to you when you don’t understand?

— Understanding, — he says, — I don’t understand badly, but I can’t speak Yiddish at all. You’re a Yiddish poet, though, it would be, on my part, impolite, if you shouldn’t speak your language on my account. I feel great deference to a poet.

— That’s very noble, — I say, — but when you say that I should speak my language, it makes me sad. Sad that you underscore that my language isn’t yours.

— And you consider Hebrew your language? — He asks, and his eyes give a flash.

— Of course, — I say, — of course. And of this consists the great difference between us. But we’re not carrying on an argument between us here in the hospital about our languages. Something else in you disturbs me. Yesterday, when you were with me, you spoke about yourself and about your unique approach to all Jewish problems and every word of yours simply pained me. I wasn’t physically strong enough to argue with you. The truth is that I don’t have any strength for it today, either.

— If it’s difficult for you, I’ll leave you to rest. I’ll go to my room.

— No, you don’t have to leave. I’ll tell you the truth: You make me happy, although your way of thinking seems strange to me. I would like to grasp it. I want to understand how a young Jewish man comes to such an un-Jewish approach to the entirety of Jewish fate and being, as you allowed yourself to express yesterday. You said that neither Jewish destiny nor Jewish being concerned you.

— You didn’t understand me properly, — says the young man, — I didn’t tell you that Jewish destiny doesn’t concern me. It does concern me. I only said that Jewish destiny, as you understand and accept it, in the long, historical sense, in the mystical diasporic sense, as well as even in the biblical sense, as Ben Gurion conceives it, this Jewish destiny doesn’t concern me. I don’t want to bear it, not on me and not in me. And permit me to speak and you, just listen if if it is difficult for you to talk. And I indeed want for you to understand me. You shouldn’t think: I know, a Sabra there, a savage Israeli boy, uneducated, babbling there. I’m no savage: I’ve read a lot, both Jewish history and our literature. True indeed, I know very little Yiddish literature, but I don’t, God forbid, deny it. I’m sure that it possesses great, worthy writers and works. I am acquainted with Jewish philosophy and also with a bit of Kabbalah. I don’t deny any of the great things which were created in exile and the deeds of past great generations of Jews. But I want for you to know that I can get by without them. What’s more: I don’t want for them to even lie on my consciousness, that they might oppress my spirit and that they might demand something of me. Do you understand? Demand!

— You speak about our diaspora-words and diaspora-epoch even more harshly than Ben Gurion expressed it in his correspondence with Dr Rosenstreich. You’ve probably read that.

— Of course I read it. I’m also already acquainted with the contents of your speech at the conference last week. A friend related it to me. I want to tell you that you didn’t address it correctly at all. To whom did you speak and to whom did you argue? To the old, to people of the older generation, who, even if they think they don’t agree with you, they feel you. They are indeed Israeli Jews, but at their core they are still yours. They are, like you, generations-of-history Jews, or generations-of-faith Jews. They are still, like you, kiddush hashem Jews, or kiddush ha’am Jews.2 But I, and those like me, are just ordinary Jews, and no more. Jews without the leaden seal of generations and of kiddush. We don’t need any lead. Nor do we need Ben Gurion’s biblical lead. You think that Ben Gurion’s thought differs from your own? Wrong. In truth, he thinks the same as you. He’s drawn to the leaden seal of holiness and to continuity no less than you are. He only wishes to speak differently than you speak. And if you think that we, the new, young generation in Israel, follow Ben Gurion in his idea to leap over exile and leap straight into the era of Joshua Ben Nun, if you think so, you’re mistaken. Not us who follow Ben Gurion, but he follows us. Ben Gurion says what we say. But he doesn’t understand us either. What relevance your words at the conference, as sincere as they were, as true as they were, according to their conception, according to their non-Israel world scope, if you didn’t speak them at the right place, to the right addressee? You needed to speak to us; to us, young sons of Israel; to those who were born here and grown up with the sole privilege of being born here. Yes, the one and only privilege. A simple privilege of nature. No more, no other privilege do I need, I need no one. Because of that privilege, I went to the Sinai action and I will go to other actions if they are necessary to defend and save my little bit of homeland. I give up my life for it. For it, and not for anything else. Not for what you spoke about in your talk. If you had given your speech to us, to those like me, you would immediately feel that you came to us with a mission, as though it would happen that without that mission, I have no right to live. You want to crown me, and those like me, with a crown that we don’t wish to bear. We don’t want any crown on our heads. It might be the most beautiful Jewish crown, I don’t want it. Just as I want no hump on my back, so I want no crown on my head.

— You talk, — I say, — very emphatically and very outspokenly. You don’t want any crown on your head, what if, though, the crown is there?

— What does that mean: It’s there? — my young Israeli fellow-patient becomes more impassions and sharper. His eyes become filled with flames. All of his handsome face trembles. — What does that mean: it’s there? How is it, as I don’t want it? I want to be free of it. I do not want to be crowned. I do not want any crown. You all bear yourselves around with a Jewish crown. But we don’t need any burdensome, inherited crowns. I know you’ll say: Canaanite. I know. But I tell you that it isn’t true. Nor do I want to be a Canaanite and I am not. I need no idols nor any gods. I don’t need to exist in someone’s lineage. For me, my own personal privilege is enough. I don’t need to leap and leap over. I need no leaping in, neither into the days of Isaiah Ben Amoz nor into the days of Joshua Ben Nun. Who and what I am is enough for me. All the gods and also the Lord of the World ought to leave us alone. He ought to leave us alone with His crown which He continues to put on us after He singes our heads enough with all the terrible fires…

I sit on the bed, listening to the boy’s surging, zealous words and I think: Of course this young man isn’t the barometer for the entire youth of Israel, but he is symptomatic. And he is even more symptomatic to me in that he is also strangely sympathetic. He truly exudes tragedy. His eyes are filled with burning sorrow. When he finishes speaking, I say to him:

— You would be correct if you’d said what you said over three and a half thousand years ago; if you said it, not to me, but to the young Abraham, in the house of his father, Terah. Then you would, perhaps, be correct; and even if not correct, you would have been in the correct place to say it. But now, my dear friend, you’re more than three and a half thousand years too late. It’s hopeless. It won’t help you today. Whether you want to carry the Jewish crown or not, you must bear it; you are sentenced to carry it.

— Sentenced?! — Shouts my young conversationalist.

— Yes, sentenced to bear the Jewish crown. Unless you wish to make a hump of it for yourself. You can do this, as well. You’d be sentenced to carry the hump. But you must carry something.

— I must?!

— Yes, my friend, you must! And if you must, why carry a hump? Better to bear a crown.

The boy looked at me with his smouldering eyes, his lips trembling like a child’s. He left my room. I see how, over his head, there descends the inevitable Jewish crown. He stretches out his hand to push it away from him, but it doesn’t help him. The crown puts itself on his head. He strides away with it, he moves away from me, but I see the crown, bright, above his head.

And strange, immediately afterward there comes into my room the old man with the rabbinical kapelush on his head, the old-fashioned blesser. He goes to each patient, spreads his hands out over them, and says a blessing. He also approaches me. I see well his wrinkled face, his peyos under his kapelush. His hands — white. His fingers — long. His beard — grey. His lips, beneath his moustache, move quickly. He spreads his hands out over me with mercy, fatherly.

H. Leivick, Tog, 8 February, 1958

A postcard which Leivick sent from the Eden Hotel (where Leivick will continue his recovery, stamped such on the reverse) in Jerusalem to Chaim Grade in 1957, borrowed from the Grade Archive at the Center for Jewish History/YIVO

Rachel Yanait Ben-Zvi, author, educator and the second First Lady of Israel. One of the founding members of Poale Zion in Palestine

The difference between being honouring God and honouring the Jewish people. Or, perhaps, being ready to martyr oneself for one or the other, in some cases.