Leivick in Israel 1957, Part 5

The Beautiful Cultural Garden of Israel: Impressions From My Israel Trip

Part 4 is here. Part 1 may be found here. Translation (and mistakes my own)

The Beautiful Cultural Garden of Israel: Impressions From My Israel Trip

In my previous articles about the ‘Theoretical Conference’ in Jerusalem and about my impressions of the general current cultural situation in Israel, I remarked that the voice of today’s Jewish youth was absent at the conference — both of the youth of Israel and those from outside the country. I noted it, because at the same time that the conference was underway in Jerusalem and afterward, as well, I came to read in the Israeli press a large number of very important, sympathetic articles about the intellectual state of today’s Israeli youth, about their searching, cultural position, demands and dissatisfaction; about the self-sacrificing devotion to the land and to the people on one hand and about the suddenly standing and asking oneself: We — this generation, the one born in Israel — who are we and what are we?

I surmise that the unease of spirit that comes to be expressed in a number of articles by very important writers — representatives of the current generation in Israel, such as Moshe Shamir, for example — that this anxiety which leads to a reappraisal of words and to recognition of past cultural mistakes in the upbringing of the young generation, in the attitude to the politically near-Stalinist Left, as well as in the attitude toward the whole course of Jewish generations, has not only just now arisen in the hearts of the responsible segment of the Israeli youth. It is an unrest which already smouldered. What is more — it has arisen in its full, clear expression and with much scope, openness and earnestness. And it will certainly lead to profound, wished-for, positive attitudes regarding the entirety of Jewish existence, in its newly-revealed yearning to cross over from negation to affirmation.

I expect that I will not be out of order if I should say that the recently occurred scientific and ideological congresses in Jerusalem and, in relation to them, the outbreak of arguments about people, Zionism, messianism, approach to diaspora and to all of Jewish history — that these events have still more awakened the intellectual unrest in the hearts of the creative representatives of the present generation in Israel.

And — once again — a great pity that this unrest came to be expressed only in the pages of the newspapers and periodicals and not at the conferences themselves, through passionate words, face to face.

Because of the fact that in Jerusalem, after the theoretical conference, I became unwell and because of that had to almost a month in isolation, I had a very good opportunity to follow almost the whole press in Israel (healthy, it is entirely impossible to surrender oneself to such a luxury — to swim in a flood of newspapers, as is the case in Israel), both in Hebrew and in Yiddish. And I was pleasantly surprised to feel how sincerely and profoundly the intellectual unrest and longing for a reevaluation of words captured the hearts of creative writers. In the great, energetic cultural garden of Israel, these longings are now the most wide-spread, blooming beauties. They have a connection not only with the literature, with the leadership of the country, with the struggle for existence; they are connected still more with the most essential of all things — with the shaping of the new Jewish generation, upon which depends the entire shaping of a people.

So it is in Israel. So it is in America, as well.

And if in America, the matter can be considered, may be approached a bit lazily, a bit sleepily, dependently, even blindly — in Israel, though, it cannot be approached so. There, one cannot depend on a ‘in any case’ on an ‘around’ or on the mistress ‘Time.’ In the forming of one’s own state life and one’s own, full, Jewish, complete school and upbringing, cultural and intellectual matters arise quickly, in their full criticality.

Does a Jewish child need, through their upbringing, to be connected in their entire being with the whole essence of our people through generations and, consequently, with the whole essence of our people through its presence everywhere today — this question is, for the generation presently being raised in Israel, no abstraction, nor can it be put aside. Upon this there also depends the whole state of the literature, its influence and its growth. Does the literature which is created in Israel need to be a fully-Jewish literature, a fully-generational literature — not in conflict but, on the contrary, in full, warm, intimate cooperation with all that which Jews of their own nation have created and also create today everywhere in the world, where they live? Or does it need to be not other than a Joshua-Ben-Nun-literature, even a Isaiah-literature?

The arguments around this and the attitude of a large portion of revising intellectuals in Israel, born in Israel itself — they and their work are the flowers which fill the present cultural garden in Israel. They are those who it, Ben Gurion’s daringly uttered idea about skipping over exile and stepping into the age of Joshua Ben Nun, drove into a self-reflective argument against themselves, their Jewish prosecution.

Precisely them, those born in Eretz Yisroel,1 in the land of Joshua Ben Nun, who were frightened by such a leap. Precisely them who quailed before emptiness of history, who were pained. Sensing the terror before such an emptiness, their hearts were filled with a nostalgia, with a yearning for the beautiful words of the exile-Jew, for the Polish and Lithuanian shtetls which disappeared into fire, for the lives and generations which are no longer here. Some of the more nostalgic, the most hard-working in opposition and in negation toward the diaspora and in ignorance regarding Jewish creativity in exile, even felt themselves as sinning against Yiddish and against the great literature which has arisen in Yiddish and which remained outside their personal intellectual world.

It is characteristic that this vestige of poisonous, deranged hatred toward Yiddish and toward Yiddish literature, is still found in places in Israel today, mostly amongst those who were not born in Israel and were not engaged in the full climate of the country. By those haters of Yiddish and of the Jew in the diaspora (Yes, they truly hate this Jew!) and of all which the Jew has created in his life in the diaspora — by them this hatred is truly transformed into a neurosis (as I had already presented in my speech at the conference),2 truly into a sickness of the spirit which, if one wishes, one can only pity them, those who hate. They represent, though, the nettles and thorns in the beautiful cultural garden in Israel.

I am nearly certain that Ben Gurion took no pleasure that such cultural neurotics seize, heart and soul, upon his idea about leaping over exile. In him, Ben Gurion, it certainly comes from inner experience, from a dramatic feeling of taking a dramatic historical risk, and although I am, with my entire being, against such a position as his, and I consider suck a risk a dangerous one, I do not despair, though, as it comes to him from a profound experience. The nettle and thorn writers, though, the neurotics — that they seize upon the idea of leaping over exile, they don’t know at all, then, what sort of world they are. They then begin to drift right and left with hatred, and start to talk and write about the Jew in the diaspora — about Yiddish and about Yiddish literature, with the hatred of an enemy of Israel. Yes, this is the nettle in the beautiful flower garden of the State of Israel.

I will write about the nettle writer again a bit later, although it isn’t worth concerning oneself with them; one ought to ignore them — but as soon as they take their place in the garden, one cannot pass them by. Particularly when they flail their arms around and agitate.

I say this against the fact our own nettle plants sprang up while I was in Israel. Both in relation to the attentiveness with which the most part of the intellectual world in Israel received my words at the conference. Words, which although they touched the sharpest points of our cultural and existential problems, they summoned forth a wished-for creative stimulation and not upset, as the nettle had wanted; both in connection with our cultural and literary events, which the writer of these lines had, as a guest, was caused, and once again— was not caused, God forbid, severe upset, but well creatively stimulated. May the reader forgive that I touch upon things connected to me personally.

In the meantime, though, we speak about the flowers in the cultural garden in Israel — about the beauty. Beauty which is reflected in artistic work, in uplifted poetry, in fresh prose, in actively empathetic journalism, in daring, earnest accounting of the soul. — An accounting of the soul which, as it has already begun with full force, will need to go down the line of an all-national, all-encompassing thought.

As a model of the accounting of the soul, I will present reactions from some of the true writers in Israel regarding this argument which happened between Ben Gurion and Dr Rotenstreich in a printed exchange of letters between them. The same argument about which sharp complaints were also heard at the conference in Jerusalem.

For a portion of the true young writers in Israel, for the true ones who indeed undergo an accounting of the soul, Ben Gurion’s daring ideas were unsettling.

At the core, they would need agree with Ben Gurion, both because of Ben Gurion’s great authority and in the sum of their upbringing, which they received in an atmosphere of repudiating the diaspora. The idea of leaping over exile would need to appeal to them, to find favour in their eyes. It would, of course, free them from difficult, burdensome problems. It would make their lives easier. — You see though! Carefree living doesn’t appeal at all to this portion of Israeli youth who suddenly feel a push toward historical and national responsibility. And this push comes from many directions. Both externally and internally. It could come from the national and governmental struggles. It could come from the social contradictions in national life. It could come because of of the streaming in of Jews from so many countries and cultural atmospheres due to the differences in their ways of life and because of the revelation of their differences of needs and character. And most of all, the push can come from themselves — through a process of an inner moral awakening, from an unrest in oneself which interrupts habit and ideas, instead seeking within them new ideas and new elevation.

Conveniently, this intellectual brightness stirs the creative youth to run away from it, this warming brightness. It sets before them anew, and on their own earth, under their own sky, the question: Who am I? What is a Jew? What is it that makes me a Jew? And what connection do I have with another Jew, somewhere over there, on the other side of the border. Is it enough for me that the sole Jewish fact about me is that I was born in Eretz Yisroel? Should that be enough for me? — They ask such questions, which also begin, in partially, to be asked in America: What is it that makes me a Jew in America? May I be satisfied only with the fact that I was born a Jew and I need do and accomplish nothing more?

It will be, I believe, interesting for the reader to acquaint themselves both with the arguments of the creative writers in Israel, with the essence of their current serious quarrel, as well as with, necessarily, the arguments of the uncreative nettle-writers.

In the next article, I will attempt to provide examples of these.

H. Leivick, Tog, 7 December, 1957

Onward to Part 6

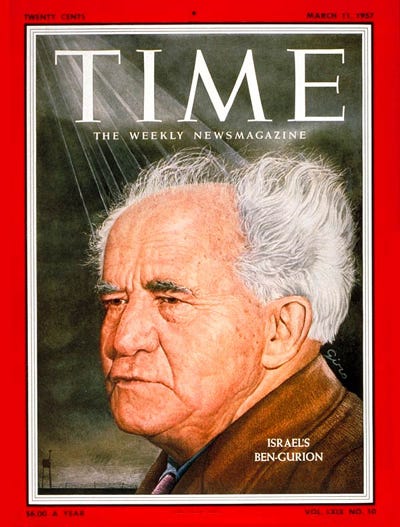

Ben Gurion again, this time from Time in 1957. He’s going to be something of a theme on this trip. He was a bit of one on Leivick’s trip in 1950, too.

A small note regarding my usage of Eretz Yisroel v Israel/State of Israel. I am attempting to keep Leivick’s own differentiation between the two — in part, that of the religious, traditional and, crucially for Leivick, messianic ideal of a promised land for Jews versus that of the modern political state, respectively. Sometimes the boundaries blur, particularly in discussion of Ben Gurion’s idea of picking up where the Tanakh left off.

That’s ‘Der Yid — Der Yochid’ (The Jew — The Individual) which really is a spectacular thing and deserves a better and bigger platform than this newsletter/blog/diary.