This has turned into something of an occasional — and more than a bit chaotic — series, beginning in 1919’s Poems (Lieder) with one of Leivick’s first father-poems.

Of course, I have no way of telling what, precisely, the first father-poem actually was (yet?) because we have to play by Leivick’s own rules more than a bit in looking at his career and his own, self-constructed identity and image if we don’t have access to letters, archives, etc.

‘Ergets Vayt, Ergets Vayt’ may be the first poem of the 1940 Ale Verk and the first of Lieder,1 but was certainly not his first published poem — that honour surely goes to ‘Prison Motifs,’ printed in the Forverts’s weekly Zeitgeist magazine in 1907 under the name Leivick Galpern, when Leivick was still in prison in Minsk.2 There were also poems printed in Philadelphia’s Jewish World (Yidishe Velt) which S. Charney couldn’t find for his massive Leivick book of 1951 and which Leivick either didn’t have himself or didn’t feel like sharing. ‘Ergets Vayt’ merely represents the first time he felt as though he’d found his own voice — the moment it all clicked.

So ‘The Severe Father,’ while certainly early, isn’t necessarily the first. But isn’t necessarily not.

1919 is an important year for Leivick for another reason, as it’s the year he first becomes a father himself.3 We’ve already seen little hints of this before — the boy playing in the snow in the cycle ‘My Father,’ in 1932’s Naye Lider, for instance. And just as Leivick’s ghostly father seems to stand over him in ‘Dozing Boy’ from In Keynems Land (1923) we also see a flesh and blood version of Leivick standing over a bed, looking down at a child (‘The Grown Father’) and yet another version of Leivick who can’t put on his prepared shroud and entertain the thought of death for too long yet — lest the shroud be dyed red in the blood of his wife and child (‘There, Where I am Not Yet’). Two blond boys sit at the table in ‘New York in Beauty’ (from 1932’s Naye Lider) and one tries to snap their out-of-work father out of his wounded pride and despair.4

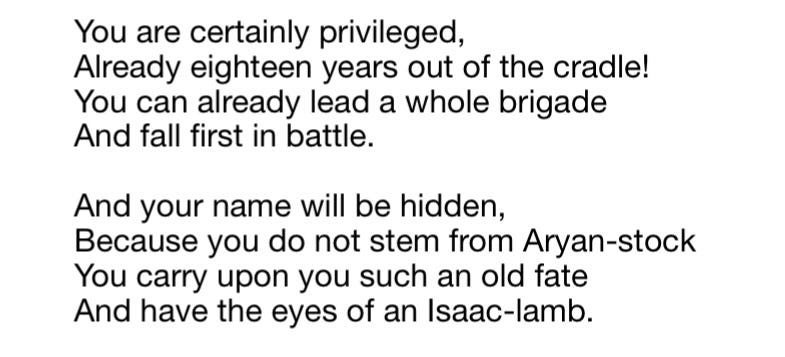

‘Be Ready, Daniel, for War’ from 1937’s Lider fun Gan Eyden directly addresses his eldest son, on the eve of what will prove to be the Second World War. Here, Leivick views his son and the sacrifice he foresees he will be asked to make to a false god, for a country who ‘seeks the Shylock’ in Jews, and to a profane one, in the form of Hitler, through the lens of that great fixation of his, the Akeydah.5

His son has ‘eyes of an Isaac-lamb’; an image he will revisit in a similar, highly personal way in the dedication of In the Days of Job, in a poem addressed to one of his grandsons — one of Daniel’s own sons.

Leivick sees, of course, the repeating cycle of fathers and sons, of sacrifice, from Abraham and Isaac down to his own family. And he sees it extending beyond that, unless something occurs to finally stop it.

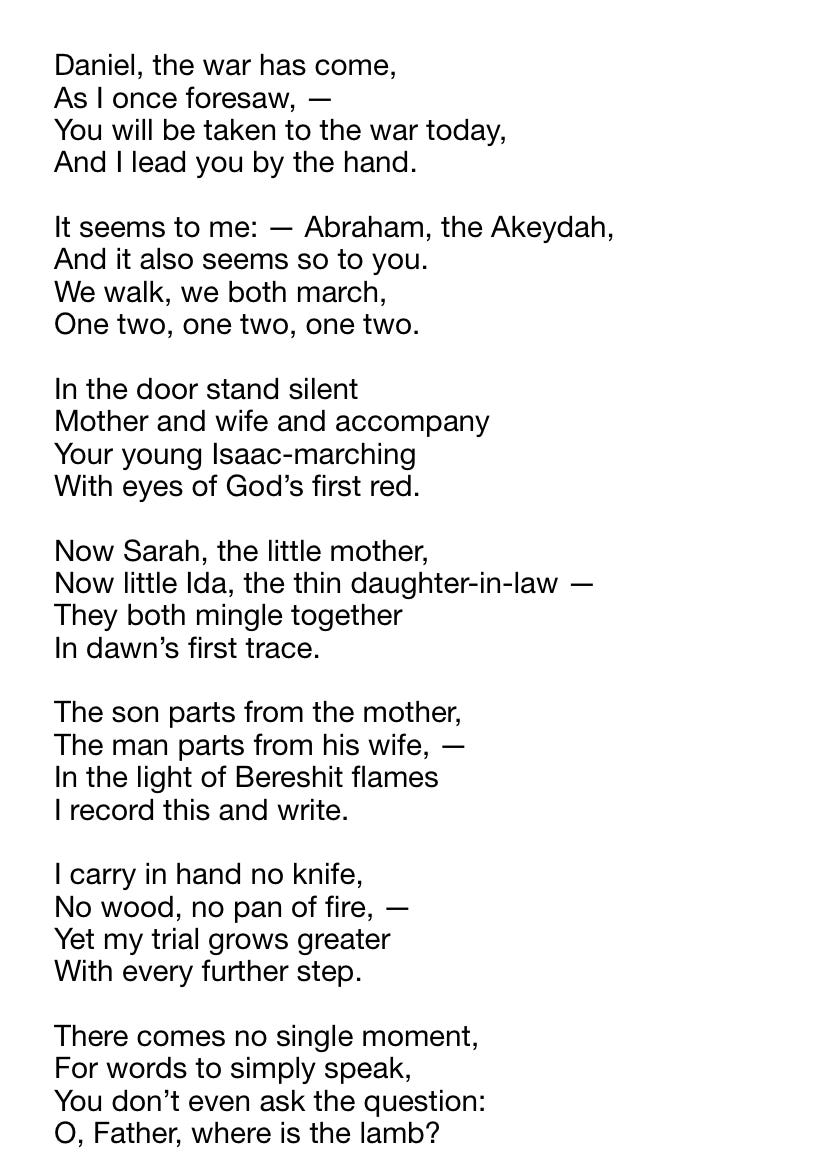

We pick up the same thread, with a more fully realised parallel of the Akeydah, in 1942’s ‘Daniel Goes to War,‘ published in I Was Not in Treblinka (1945).

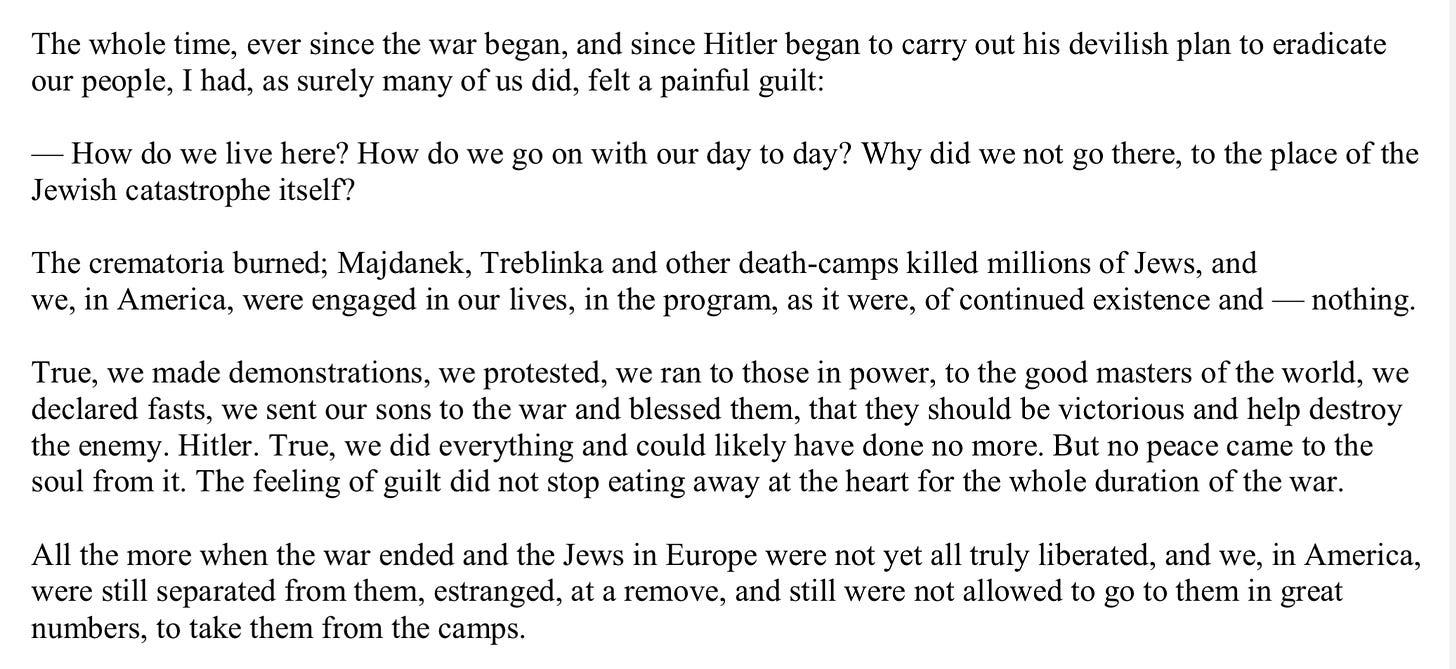

It’s a particularly striking poem to me in light of Leivick’s writing in With the Surviving Remnant (1947). There, he recounts everything the Jewish community had done in America during and immediately following the war, classing it all as far too little.

This sending of sons to war, though he never mentions it in the text itself,6 isn’t an abstract notion to him of course, as we’ve just seen: It’s a highly personal one. It’s something that he, himself, has done. And though poem ends on a note of hope, of victory, there is still the sense of an impending sacrifice upon the altar of the profane.

Alongside this image of Leivick as father marching his son off to potential sacrifice, — and slightly earlier ones in 1940’s cycle ‘Songs About the Yellow Patch,’ which see Leivick imagining his own family wearing yellow stars, marked out as Jews under a Nazi regime — we get still more images of his own father, whose death has not stopped him being aware of and touched by the war and the unfolding tragedy in Europe.

Poems such as ‘A Letter From My Father, A”H’ becomes yet another reflection on ‘there, where I am not,’ treating the situation where Leivick could have found himself had fate not intervened. And in ‘My Father Used To Call It Chatzos,’ Leivick reflects both how like and how unalike his and his father’s interrupted sleep is — Leivick’s father rising at midnight for prayer during his childhood, and Leivick rising to, well, pray in his own way in 1939. Or, at least, to dread and write poetry.

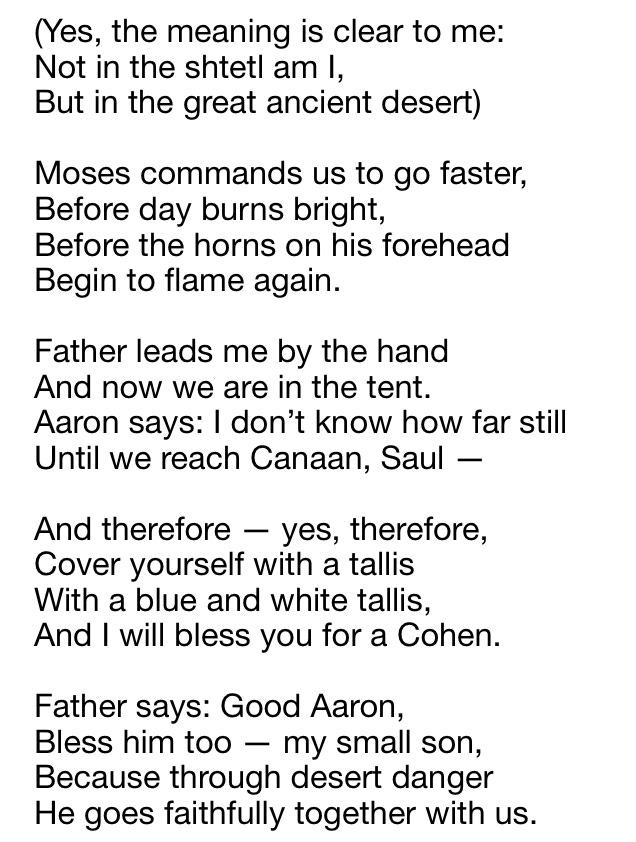

Saul — as well as Leivick’s mother, Esther, and his childhood teacher, Shimon-Leyb — appears again in a long poem of roughly the same period, ‘Ballad of the Desert,’ published in I Was Not In Treblinka. And what an extraordinary poem it is (in my estimation), with all of his hometown present at the foot of Sinai. His father is taken to be blessed as a priest — and demands his son Levi be taken with and blessed as well.

The plot roughly unfolds as in the Tanakh. The tablets are broken, the old generation, including Leivick’s parents, are sentenced to die in the desert. 7

And, as in ‘Letter From My Father, A”H,’ Saul has a vision of a terrible future of yellow patches and gives a sort of prophecy — in reality, of course, no prophecy at all, but another of Leivick’s relations of actual world events within a religiously inspired framework. In fact, Leivick flashes forwards from Moses’s death on Mount Nebo to all the various humiliations and torments which Jews will undergo between Sinai and, well, the coming of the Moshiach. And then the poem’s ‘Levi’ lives through them himself.8

Both his mother and father return to him at the close of the poem, after all the horrors, seemingly unmarked by death, at what is presumably the resurrection of the dead with the arrival of the Moshiach.9

At last, we reach the ‘Ballad of My Father’s Portrait.’ And it’s an expression of both these horrors of the times and deep familial bonds and love. While we saw back in Poem X of the cycle ‘Lider fun Umkum’ how Leivick identified traits within himself which came from his father, there those traits were all negative ones.

Here, the elder Halpern uses them, their innate resemblance to one another, to bring the younger to a sort of safety.

Again, we see the Akeydah motif and a profane god, as what are presumably Nazis beat down the door and demand that a son is sacrificed. But Saul, unlike Abraham, refuses, first offering himself in place of him and changing places.

It is, of course, all a sophisticated bit of ventriloquism. Leivick can make the Saul of his poetry say and do anything he likes, be the father he wanted to have. But I don’t think he’s really reaching for anything. As Leivick writes in ‘Father-Legend’ (in 1932’s Naye Lider), writing in his father’s voice, he believed that the impulse, if not the means or ability, was always there:

Carry on your hand all of my touches,

Carry on your lips my kisses,

Which I wanted and should have

And was always ashamed to give you. 10

To be continued…

Another brief, below the line note from me. I don’t hold the rights to anything here. If you do and wish it removed, please get in touch. Any and all personal information is gleaned from published material available to anyone with an interest (and the ability to read Yiddish), mostly from Leivick himself, and is presented with the best of intentions and respect. All translations and mistakes my own.

I do often wonder about the portrait of his father that Leivick mentions and wonder if it is indeed the woodcut that he had made from the photograph of himself with his father and mother — he seemingly had it made into two separate portraits by B. Reder, one of his father, one of his mother, which he hung on opposite walls of his office/work-room.

I’m simplifying, Leivick’s first couple collections, as far as I understand it, are rolled into Lieder.

S. Charney notes it’s derivative of Reyzen, and it is!

Leivick had two sons, Daniel and Samuel. While both are mentioned in his poetry and elsewhere — In the Days of Job is dedicated to the both of them — it’s Daniel who seems to appear most often and who receives direct address.

Leon Gildin’s translation of this particular poem inserts the family’s names, which do not appear in the original. Gildin, according to the introduction to his volume, The Poems of H. Leivick and Others: Yiddish Poetry in Translation, was a close friend of Leivick’s younger son, Samuel.

Two of his plays, Akeydah (1933) and In the Days of Job (1953) touch in depth on the bones of the story, but have very different approaches which seems very connected to the times and circumstances of their compositions. Hopefully, more on this later!

Leivick keeps his cards fairly close to his chest here. It’s in his co-delegate Israel Efros’s book that we learn he’s also just become a grandfather.

The story revisited slightly more straightforwardly in Leivick’s 1953 play, Gezer (‘Sentence’ or ‘Decree’). This, too, is an amazing play in my estimation, even if I had to hack through it in Hebrew with a dictionary. It was very worth the struggle.

I render ‘Levi,’ the proper form of Leivick’s name, in quotes here because, as usual, it both is and isn’t him. It’s another self, another mask.

I half believe, at times, that Leivick was convinced the Second World War was the form that the war between Gog and Magog — which is part of the traditional Jewish conception of end of days and immediately anticipates the arrival of the Moshiach — was going to take.

I am going sailing over ‘Father-Legend’ and others, but you can find a bit about Cynthia Ozick’s process and her start on translating ‘Father-Legend’ here. Ozick did quite a few translations of Leivick which I admire very much. Perhaps my own failings lie in the fact I don’t feel that sort of ‘possession’ which she describes.