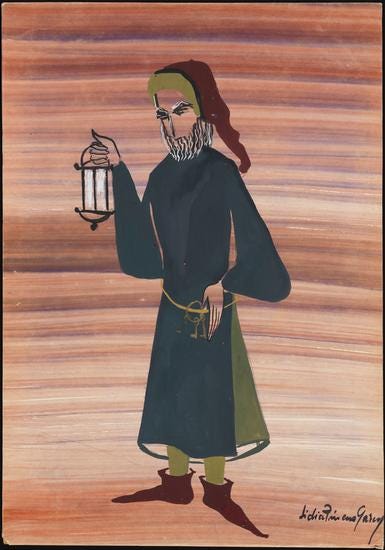

Knup, Costume design for Maharam of Rothenburg, from the Museum of the City of New York, Accession 65.83.7

The Jewish apostate is a figure that shows up with some frequency in Leivick’s dramas —

a contrast to the gentile who is granted an honorary Judaism (Or, at the least, made un-Christian, such as in the case of Abelard in Abelard and Heloise).

Professor Shelling (Who’s Who), who denies his Judaism, is one of these figures, though perhaps the least virulent as he might hide, but he does not convert. Victor of Miracle in the Ghetto is another — he attempts to feed his family and hide his younger brother (who flees from him to rejoin the others)— but he is assimilated and intermarried, hiding amongst the Poles. Tellingly, perhaps, given the importance of language to Leivick, he is a teacher of Polish. Wanda and her father (also Miracle in the Ghetto) have converted, but return — her father out of necessity, Wanda out of sincere desire to be with her people.

And then there’s Knup.

Knup has his own brand of Jewish rage, which he turns on his own. He’s been spurned by his own people: rejected in his desire to marry the Maharam’s daughter, a poor student, his parentage uncertain. Is some respects, he shares a biography with Leivick’s cellmate (and townsman) Urke in In Tsarist Katorga. But while Urke is sometimes willing to show his better nature and a certain pride in being a Jew, Knup has none of these redeeming features. In response to his treatment, he’s become not a mere petty criminal, apostate or willing non-participant in Jewish life, but a virulent antisemite in the service of the Count and the Emperor.

Knup’s the odd man out in ‘borrowed’ clothes. Though he is dressed like a knight, rather than in Judenhüt or yellow star, one of his new colleagues says that while he might be baptised now, a ‘A Jude is a Jude.’ Knup himself says he wants to live in both worlds and have the best of them — to be a Jew with none of the danger or suffering when that life turns tragic.

To be neither one nor the other, however, is untenable. Knup, too, for all his denials of his Judaism, cannot escape Jewish fate, just as those who converted out or assimilated could not escape in Daniel’s time. And this fragmentation has seemingly driven him mad. And in Leivick, the madman often speaks some degree of the truth.1

H. Leivick, Maharam of Rothenburg, 1945.

Back in Mainz, 1286, Knup is the first to spy the visitors from Dachau, 1943, and underscores one of these patterns of history which enable the play’s time travel — for the audience as well as the character: he can see that they’re Jews by their clothes. The Jews of his own time, too, have mandated clothing which sets them apart. Incidentally, they all recognise each other repeatedly as Jews by the fact that they are wearing this punitive clothing — Judenhuten on the part of the Maharam and co, yellow stars on our time-travellers. Daniel refuses to remove his star when encouraged, from fear of reprisal, but we know from elsewhere in his poetry and drama that Leivick views the yellow star as a mark of pride.2

As with Chains, to mention every instance where Leivick is drawing a parallel between a real-world experience and a dramatic one, I would have to essentially reprint the entire text. For example, the fifth scene open with groups of Jews are huddled into an inn, waiting for their opportunity to cross the German borders to escape.3

But it’s impossible not to be moved to mention the Jewish refugees from Mainz at the border, struggling with the ideas and opposites of bloody land, homeland, promised land, holy land, dream land, exile land. And the Maharam’s intense guilt for abandoning his people in exile — the survivor (or ‘not being there’) guilt that often appears in Leivick’s work of this period, namely in his collection I Was Not in Treblinka. We’re right back to Hillel in Pirkei Avot: Do not separate yourself from the community. Why should anyone be safe and saved if there is one who is not?

H. Leivick, Maharam of Rothenburg, 1945.

While we learn these lessons from the tragedy of Jewish history and recognise its patterns, we’re also meant to draw some strength and comfort from it. Daniel wants the Maharam’s blessing, and declares himself a ruin, annihilated: a khorev.4 He wants blessing from someone who endured his captivity without surrender in order to make himself whole again. He desires comfort from not only the physical contact of the blessing, but the knowledge that the Jewish people have endured despite oppression, imprisonments and slaughter in order to repeat that cycle — and it’s all cycles and circles in Leivick.

This is paired with the acknowledgment that everyone, essentially, even in a community, suffers and dies alone, for themselves. But finding you ‘opposite number,’ even seven hundred years removed, can offer you a bit of consolation in knowing you’re not the only one. Prison is, Daniel tells us, one of these ‘doors’ which leads from one age to another. All prisons and shadows are the same — they flow together, entwine.

Guard, Costume design for Maharam of Rothenburg, from the Museum of the City of New York, Accession 65.83.6

Time begins to accelerate. Highly intentionally, I think. Scene Five finds us a at least a week after Scene Four. Scene Six takes place a year after that. Scene Seven — Seven years later. And, to finish the play, there is one last, unspecified, jump in time. Leivick writes specifically about time in relation to his own imprisonment: how it took on a solid, palpable form. If seven hundred years is, as Ahasver tells us, a stride, then what’s seven years? You can do that sitting in your chair in the audience.

Daniel says he has spent seven years willingly with the Maharam, walking freely into his cell, and while we never see him return to Dachau on stage, not as he was in the prologue and we don’t know how long he spends there — he does say throughout that he is both there and somewhere else.

He and Ahasver seem ready to go on further wanderings at the close of the play but, because we have been told that one can be awake and asleep at the same time, is it only his only his mind, his unconscious which is free? Is this the bit of him that will always be free and defiant despite physical captivity? Leivick himself mentions passing through the walls of his own prison, even if only in the mind’s eye.

In Scene Seven, there is some external stressor which interrupts Daniel’s time with the Maharam. He must, he tells him, return to the concentration camp. And explains to the Maharam what, exactly, this is. Daniel melts back into the shadows, seemingly upon being awoken into his own reality.5 We learn that the worse his physical situation in the camp becomes, the less he is able to come. He cannot escape into the past, into dreams, so easily as before.

What, then does it mean when Daniel returns and he and Ahasver bend to ‘wake’ the dead Maharal to come with them on their further travels? Is it a different sort of free? Is Daniel, in fact, now dead himself?

Or is it only sleep and it is rather only the story of the Maharam that Daniel will continue to take with him, through dreams, through his own prisons? Certainly Daniel’s completion of the verse from Psalm 23 as he leans over the Maharam (‘for thou are with me’) suggests this.6 Does Daniel ever truly attain the detachment that Ahasver says comes with the Jews who know they are crossing the threshold of death? Perhaps he does, as Ahasver says that it isn’t the Maharam who lies there at all — the Maharam will be coming with them — and Daniel readily participates in the raising.

Are Daniel and the Maharam merely stories to comfort and console each other? A means for each of them to see his history or future and know he is part of a Jewish continuity?

I include the Maharam as dreaming Daniel, because find it hard to relegate the Maharam’s drama to the realm of only Daniel’s dream, because we are still witness to his life when Daniel isn’t present. We are told the Maharam is also half-asleep, half-dreaming in the final scene. If it is only a dream (or death) and only Daniel’s, why must he be so carefully guarded against telling the Jews of 13th century Mainz what will happen to them?

If one prison is all prisons, and one shadow all shadows, is one dream all dreams — the collective Jewish unconscious in which travel happens forwards as well as backwards, as time is circular and repeating?

H. Leivick, Maharam of Rothenburg, 1945.

Furthermore, the Maharam does hear the strangled cry which might come from Daniel’s Dachau reality just as much as it comes from Knup in his own. If we are only in a dream, I think it must be the Maharam’s dream, as well — or his premonitions (as the Count says he has) of what is to come. What will continue to come, again and again, until the real Moshiach does arrive for good.

Leivick’s recurrent theme of compassion and consolation for the fellow sufferer is writ large here, as it will be in Job a decade later. They need each other. Leivick encourages using a living concept of history for this consolation, not necessarily fact — which might as well be addressed to the audience. Charney, in his massive book about Leivick, takes the critics who don’t heed this abandonment of ‘sober’ factuality.

The other thing that consoles is the survival of a testament — of the written word. But more a bit later on that perhaps.

Looking at this as a twin to Leivick’s other play of 1944, Miracle in the Ghetto, but a fraternal one with its advocacy of patient, holy, suffering and waiting, accepting the fact of being a prisoner and defeating the enemy via grace and dignity. It’s the other side of the story, in a way. But I think, in part, it happens because Leivick doesn’t ‘condemn’ (as much as someone essentially uninvolved has the right) either course of action. Both courses of action are sacred in their own way and to be explored.

Public taste, however, seems to have come down initially in favour of Miracle in the Ghetto, with Maharam of Rothenburg produced in 1963 by Folksbiene, while Miracle was staged in the year of its writing.

A final aside: Despite not having the language for his experiences in the concentration camp — and, looking at the dramaturg, who does in America, in 1944? What person who isn’t a survivor truly does? — Daniel is unusually good at saying that he is broken and telling what he needs emotionally: love, warmth, consolation.

He’s a version of the hero that Leivick has been repeating for years.

Daniel is part of an evolution which includes works such as Different (1922) and it’s protagonist Marcus who can only repeat endlessly that he’s changed and that there aren’t the words for what he is and what he feels. Likewise, the more emotionally open and ‘available’ Thornfeld (The Poet Went Blind, 1936) cannot speak directly regarding the state of his inner, emotional life, only relatively obliquely. Nor does he have any great desire to be whole until the very end, as being broken is what brings him most of what he has wanted — money, greater acclaim, the return of his son and his mistress.

But there is a constant emergence of and striving for a language of emotional and spiritual need in Leivick. Yisroel (Miracle in the Ghetto, 1944) is able to confess himself and his unrequited love completely — though only in the face of imminent death. Daniel can do so even when he has been removed to a situation of relative safety.

And Isaac (In the Days of Job, 1953) can announce, having emerged from danger, that he is broken, that he wants wants love — and, a step further — that he wants healing and is able to go seek it.

H. Leivick, Maharam of Rothenburg, 1945.

Avery Willard, ‘Cast of The Sage of Rottenburg with playwright H. Leivick and Golda Meir,’ Museum of the City of New York, Accession 83.85.52R. While that is Meir — then Foreign Minister — and an Israeli delegation was in attendance, the museum’s caption is incorrect: that is not H. Leivick with her, as the production was staged in 1963-4 as something of a memorial event. Meir would also speak at the opening of Leyvik House in Tel Aviv in 1970.

Knup remains neither/nor, and while he asks for the Maharam’s forgiveness when dying, neither the Count nor the Maharam seem particularly eager to claim him as their own in the end. In wanting to be both, he becomes nothing. He, himself, tells the Maharam he is no more.

He imagines wearing it himself in works like ‘Ballad of the Desert.’

There is perhaps a bit of dramatic irony in the fact that once Leivick himself was eager to get into Germany, sailing to America from Hamburg.

Related, of course, to the word Khurbn.

Ahasver urgently spurs him to go at this point, seemingly indicating that there is a real-world danger if he doesn’t return, that is to say, if he doesn’t get up/wake up.

Perhaps we are meant to read more into the presence of the closing lines of the Torah, as well, with the final words about Moses; that there will be a completion, like the writing of the Torah, and a liberation, as in the days of Moses. But Ahasver also speaks of the nature of death, how carrying the story can be a liberation beyond the physical.