I’ll preface with a small warning that this piece contains references to suicide, discussion of it a major plot point in the final act of the play.

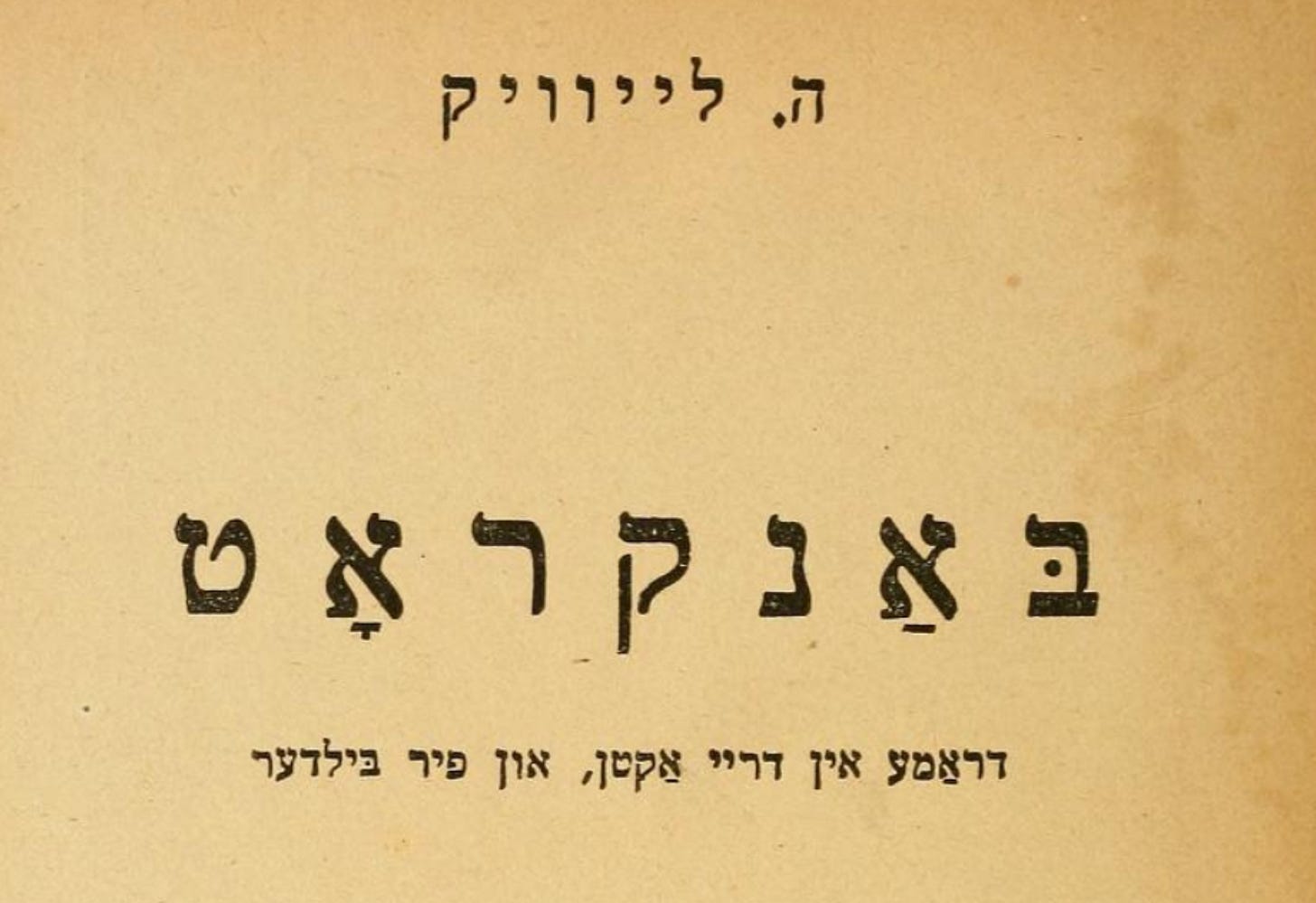

While 1924’s Bankrupt is a reworking of 1921’s flop for Schwartz’s Art Theatre, Different,

it’s also something more than a retread of the earlier play.1

Though Bankrupt’s Uri Don and Marcus (Different) have both been forced from Russia to America, the latter’s experience is far closer to the bone of Leivick’s own early life in both places. Like Leivick, Uri had been a Bundist activist in Russia, escaped from Siberia, and has now lived in America for ten years — and also like Leivick at the point of the play’s composition — has a wife and child and is facing work as a house painter. To quote Uri’s Uncle (and a point which comes to a head in Leivick’s Naye Lider almost another decade later with ‘Letter from America to a Distant Friend’) ‘you’re here ten years now and you still aren’t of this place.’2

Other details echo parts of Leivick’s personal experience as well, such as Don’s wife’s uncle, who has provided money to set him up in a shop — an American version of his own rich uncle who had briefly helped the family to set up a bakery. The most in-depth exploration of this, and Leivick’s uncle, is perhaps in Solomon Simon’s book on Leivick’s childhood. In fact, we seem to get an inverted version of a confrontation Simon describes between Leivick’s father and his brother-in-law: Saul asks for at least enough money to get back home when the bakery collapses, and Leivick’s uncle throws a ten rouble coin onto the table.3

In Bankrupt, it is Uri Don who throws the keys to the bankrupt store onto the table in front of his wife’s wealthy uncle and relations.

From H. Leivick, Bankrupt, 1927, as are all following excerpts unless noted.

Uncle’s pomp is also undercut by this vaguely ridiculous, parrot-like family (only the brother-in-law, the manual labourer, is treated with authorial respect). Perhaps this is righting a bit of a historical wrong.

I can’t help but wonder if there isn’t a more than a trace of Leivick’s own wishful thinking, as well as personal history, in both Bankrupt and Different, with the family situation of the protagonist roughly sketched out to include an absent father/father who has died, neither loved nor unloved, but with a mother who has been brought from Russia, to America, to live with her son.4 It’s not difficult to see how Leivick’s complicated relationship with his own father might inform these missing fathers and desire to have ‘rescued’ his mother.

Uri Don of Bankrupt is both more and less damaged than Different’s Marcus. The later is, ultimately, carried onwards with a sense of his own change, his need to fight. Uri’s change finds him incapable of fighting, ‘rotting,’ inside and out, most obviously to himself in an attempt to woo the cousin who is living with him and his wife. While Marcus’s drama builds up to a climactic, symbolic torching of his store, an active gesture, Uri’s opting out of life and modern society has already occurred, and is a more passive, almost Bartleby-eque one. He would rather not.

We never know for certain if Uri has intentionally bankrupted the store as Uncle claims. All that we do know is that he locked the door one morning and walked away, before the play has even begun, decrying Jewish entrepreneurship in America and these stores as temples to capitalism where the lights must always burn, ner tamid-like. What does it mean to accept this stereotype as true and still reject it?

Uri clearly isn’t much of a socialist now, either, having taken his labourer brother-in-law’s money for the cause he’s abandoned without much compunction.

The sort of sound-collage/stream of consciousness from Uri in Act One, scene ii, where we see/hear the prison experiences— the clank of the chains, commands to march — mingled in with the memory of revolutionary speeches and the distress of his present life underscore that this is a different sort of trauma than Marcus’s war. He doesn’t share his situation with many others, and there is no chorus of voices into which he can join if he chooses as there was for Marcus and Isidore in Different.

It’s perhaps the most modern and modernist element in the piece, as compared to Different’s rather more jarring and less critically-appreciated abstract expressionism.5 A solo symphony of suffering.

One of few Uri does share his essential trauma with is Luria, a man who was exiled to the same Siberian village as him and who also escaped. While Luria shares his name as some characteristics with Marcus’s business partner in Different, his personality and their relationship owe more aspects to the relationship between Marcus and his fellow-soldier and friend Isidore.6

Bankrupt’s Luria and Uri have endured similar trials before their arrival in America. They are, in fact, even closer than that — they have been involved with the same woman. But Luria knows how to work within his new society in a way that Uri does not. Luria has a freedom and a wholeness that Uri does not possess.

Bifurcated personalities, alter egos, fractured selves are, in fact, a major plot point:

Uri the idealist who was exiled to Siberia and Mister Don, beaten by life, who would pass the beating along to the idealistic Uri (as well as Luria, his old comrade, Rae, his wife, and Sophie, the believer)— and does, in a manner of speaking. Again, there’s an echo of Leivick’s own family life even in this, the frustrated father who takes his disappointments out on his own loved ones, the frustrated father who is sometimes his own twin — when that twin isn’t Death itself.

It’s always worth, in my experience, looking into Leivick’s other works of a given period, because they’re often not isolated, unconnected phenomena, but woven into his oeuvre, with threads connecting his other contemporary pieces.

With his dual nature, Uri echoes the equally-fragmented-by-trauma Rov in ‘The Wolf’ of four years earlier. At the climax of the poem, the Wolf-Rov attempts to throttle the man who has essentially taken his place at leader of prayer — here, Uri Don’s present self would (does?) strangle that man that he was.

A self-loathing monster, a pathetic one, without even the mask of a fantastical face. Only his own, metaphorically unrecognisable even to himself.

Uri’s another one of these new creatures of Leivick’s at the threshold of the 20th century again — like the Wolf, Marcus and, of course, the Golem. In fact, Uri hooks directly into the Golem and it’s connections to the Russian Revolution, as well, saying that he belongs in an attic somewhere, in the dark, away from the world. He’s certainly unsuited for this reality, much as the world and the Golem were not ready for each other7

Marcus’s sense of being different and repeating that he is different now is changed here — Uri Don accepts there is no word for it — he says doesn’t know what to call it. Something is gone, but there is something else which is growing. ‘Different’ is both too specific and too broad.

I think Leivick himself is still feeling for the correct language, the right words. And I remain uncertain if he ever does arrive at the word he is searching for. It’s a life-long pursuit for Leivick — how to say the most with the least. One theme that recurs in his poetry, over and over, from the earliest collections to the latest, is the ‘last word’ — unsaid, sometimes written, but never read. We, as readers, are never quite privy to what this word is. A strong contender, perhaps, is the unutterable name of God (perhaps in reference to his own status as a Cohen) the one word, he writes in an article for Tsukunft, to which all words reduce.

From H. Leivick, Essays and Speeches, 1963.

Is it perhaps, an expression of the divinity in man which Leivick and his characters are perpetually seeking?

Uri refuses to stick to any job, but won’t let his wife take one — does he view this as a statement of his being a bad or inadequate man? Luria holds out a promise of this sort more egalitarian relationship, just as the finisher Gertie will have in a few years’ time with Leibl the cutter in 1926’s Shop — but while Uri has talked a good, revolutionary talk in the past, he no longer lives it. He’s married a woman he doesn’t love, taking her from a man who does love her and wants to give her equality (but, it must be said, who doesn’t return Luria’s affection).

We also get a greater sense of Uri’s selfishness that we ever do of Marcus’s in Different — everything he does is because of him and it’s effect on him — with little regard to others it might affect (in this respect, he’s more like Poet Went Blind’s Maxim Thornfeld than Different’s Marcus, who just can’t help himself). He manages to reverse situation after situation to be the victim: there isn’t anything wrong with him, it’s Rae that’s at fault for being mad. Never mind that he’s the one who had suddenly withdrawn affection for her when she finds work because the family is starving and in every-deepening debt.

The fact that he’s taken money from his brother-in-law, who is able to offer his sewn-over fingers as proof that for all Uri’s talk of socialism, he isn’t afraid to deal in literal ‘blood money,’ should set our alarm bells ringing even louder.

What is Uri? Certainly no socialist any longer.

Perhaps there is a little bit, again, of Leivick’s own anxiety about ‘being a man’ and providing for his family while increasingly unwell and incapable of physical labour while intellectual labour didn’t yet provide enough. His own mother, he writes in several places, kept the family afloat (not uncommon, NB). His father, he writes, worked, but not like his mother and not while also giving birth to a total of nine children. Leivick’s not totally unsympathetic to Uri, to what is going on inside him — but at the same time we, the audience/reader, can see his manipulation. Sophie, Rae, his mother and his old friend Luria all suffer at his hands.

At the same time, Leivick never loses all his sympathy for Uri Don — and we, as readers, perhaps should not either. There are times where, even if only in a stage direction, it becomes unclear exactly how much control Uri actually has over his own actions. Some of his worst, most hurtful moments seem to be pure impulses that he is unable control. He can’t even bend himself to his own will, having been forced to flee from his home and himself a decade earlier. In this, he again resembles the Wolf and the Golem —a ‘monster’ who is subject to and created by his own grief, fear and pain. He is eternally in exile — whether Siberia or New York.8

It’s far too simple for Bankrupt, of course, to solely mean the financial state of Uri Don or his store. It’s a moral judgement placed upon him by both himself and Rae’s uncle, who funded the store. Uri is morally bankrupt. In Uncle’s eyes, this is because of his failure to assimilate into American Jewish capitalism. When Uncle accuses him of hating everyone, he emphatically agrees. In his own eyes, it’s his abandonment of what he was, what he went to prison for. He cannot muster any love for his fellow man and is even proclaimed ‘rotten’ at his own ersatz wake.

Paradoxically, though this is a very grown up game that Luria, Uri, Sophie and Rae have all played (two of them are, indeed, parents themselves), they are all still children in another sense, still at the mercy of their parents’ generation. Uri’s mother calls everyone, almost without exception, children. Uncle, too, refuses to believe that Uri is fully grown as no grown man would refuse to fit in, to be successful. No real man, he believes, would fail in business. Putting us back in mind, again, of Marcus in Different, who was precluded from being a real man by his reacting emotionally and psychologically to the horrors of war.

Luria, like the teenaged Bob in The Poet Went Blind, has been ’tramping’ for the last three years — off to see the country. This time, he says, in the summer, he’s off west. Without encumbrance of wife and child, without a workplace which he owns, he is free to run away as he likes, fleeing his life just as he once fled captivity in Siberia. Uri looks with envy on this freedom to run away. To not have an expectation of responsibility any longer.

Bankrupt does, like it’s forerunner, Different, explore what it means to be a man, particularly one who is a Jewish immigrant to America. Uri’s particular twist on the situation seems to be that precisely what made him not just a man, but a hero, in the old country is what has made him unsuited to be one in the new, American model.

New York, in these early plays by Leivick, is frequently called a Sodom — in the more strict sense of a town without pity. Here it’s also an ‘abyss’ in which a man, an Old Home hero, can be swallowed up and lost forever. It’s Uncle’s and Rae’s brother’s America of workers and those who profit off them, where behind everything door is the possibility of a private hell. Not loving it has become a crime in and of itself that must be fled, just as Uri and Luria once fled Siberia. Luria has already run from it once and wishes to again. And Uri, too, wishes to escape it.

But, as Luria says, how can Uri escape when there’s no chasm between him and mankind — he is the chasm. This, too, parallels the ‘escape’ at the end of Different, where Isidore stands ready to board a boat again and sail away from ‘civilisation,’ but, he says, how can Marcus do the same when his sorrow is too great to ever be concealed with jokes, with song and dance?

The bleakly comic chorus of Rae’s debt-collecting family in Bankrupt gives way into the black semi-humour of the play’s conclusion, starting with parade of neighbours who think he ought to be sent (back) to prison for bankrupting his shop. They also introduce the idea that Uri might already have killed himself — and set the denouement in motion.

Uri had previously reassured Sophie (and the audience) he won’t kill himself. But when he disappears between the second and third act, we’re suddenly at a remove from most of the characters of the play. Uri’s poor mother has complained that no one tells her anything — now no one left on the stage at the beginning of the third act has any real assurance of Uri’s safety.

Luria and Rae suddenly see all Uri’s apologies and words about a man who is going nowhere in a new light. Even when Sophie does finally appear, his behaviour seems to have left her with no guarantee that he won’t kill himself. The neighbours’s assumptions go spiralling wildly out of control and there are summoned more neighbours, the police, the ambulance…

Uri makes his return in the middle of what is essentially his own funeral. When they don’t find a body in his house, the crowd continues on to the next, determined to find someone dead. Possibly the nearest to pure farce that Leivick comes. But because it is Leivick, it doesn’t stay farcical for very long. Someone will pay. There is always a kheshboyn — the accounting.

In the final act, the play’s unlikely prophet — an old peddler — repeats the refrain that one must cry; When a man dies, there must be tears. He must be mourned. As Uri is certainly not dead — though he can initially convince no one of that fact — we must, therefore, not only cry but also laugh a bit. Until we see him rendered dizzy by watching his own death acted out before him, possibly realising the opportunity in this, until Luria confronts him with his own bankrupt nature, and until we, the readers, wonder what will become of him and his family after the curtain comes down. They may have learned that he really isn’t dead, but also that he doesn’t want to stay, either.

The world, the peddler says, is full of suicide. Someone, it seems, must die. He’s a bit of a spooky character, in fact, telling the crowd he’s discovered multiple suicides in the course of his work as constant visitor, recalling Leivick’s own entry into other people’s houses as a workman.9 He also denies that Uri is Uri, ultimately creating Uri’s opportunity to escape from himself. But he’s wiser than even he knows: Uri really isn’t Uri.

As alive as Uri Don may be, he is, in fact, dead.

And that’s one way of solving the fragmented self: a self or two must die, just as in ‘The Wolf’ and Golem. Mister Don kills Uri (pulls him off the ladder and beats him). Mister Don kills Mister Don (stepping off the ladder, according to the peddler). Uri Don stands and looks down on the crowd gathered in a New York street to gawk his death and carry him away just as he once looked down on the crowd gathered to hear him speak and carry him on their shoulders in Russia. Something else, neither Uri nor Mister Don, gets up — or down — and strides onward.

A final few asides:

I’ve worked from the B. Kletskin edition of 1927, which has some slight textual differences from the version which appeared in Shriftn (Winter 1925-1926), particularly in the last couple pages. Shriftn’s Uri is a bit more vocally responsive, if curt, to the attentions of his family upon his brief return, and rather than three acts and four scenes in the Kletskin edition, the play is broken into four acts. While there was no professional production of this play, I’ve found some evidence for at least two amateur versions.

It’s absolutely worth keeping an eye on the potted rubber plant in this play, because it’s a good bit of stage business and it’s telling you something about the state of Uri and Rae’s marriage: it starts the play yellow and half-dead. Why, Rae is asked, hasn’t she thrown it out? When Uri has his prison flashback, — perhaps this is precisely what it is — distraught over his love for Sophie rather than Rae, he tears a leaf off the plant and toys with it. At the climax of Act Two, he pulls on a second leaf and the whole plant comes down, shattering the pot. In Act Three, it is presumably gone.

Actually, it’s also something of a reworking of a second play, as well! There, Where Freedom, which exists in MS format (presumably held at YIVO with the rest of Leivick’s papers), written while Leivick was in Siberia and one of the few works to survive from that short period, shares some features with Bankrupt as per S. Charney’s treatment of it in his book on Leivick.

Leivick’s poetic expression of his struggles in America reaches fever pitch in Naye Lider, exacerbated by his trip to the Soviet Union in 1925, exemplified in poems like ‘Letter from America to a Distant Friend’ and ‘New York’ but his discomfort with America continues as a something of a theme until late in I Was Not In Treblinka. ‘To America’ — his fullest acceptance of and self-integration into the country— appears in 1955’s A Leaf on an Apple Tree.

I haven’t yet found this story anywhere but in Simon’s book, it seems plausible and doesn’t appear to have been refuted anywhere. Leivick was seemingly meant to live with this Uncle in Odessa and attend what was either an art or trade school. One of the ways in which Leivick supported himself in Siberia in addition to teaching and ice-breaking on the river to free boats — was painting portraits.

In fact, Different alludes to the fact that a Saul the Cohen (father to Marcus’s friend, Isidore, and sharing a name with Leivick’s father) has presumably been killed by pogromists back in Russia.

Of the two, I’d have have say that Different is the more interesting play to me, both stylistically and in terms of character. Not that Bankrupt isn’t interesting. But I find the burning of the shop and the contestant refrain about and final arrival of the ‘Liberty’ more intriguing a climax.

Both Lurias potentially owe their name to a denizen of Leivick’s hometown who was a mentally ill-man frequently tormented by the local children.

The ‘Golem’s Grandchildren’ — the shop dummies and statues of New York — and not the Golem himself, are the ones who become the real Americans in Leivick’s ‘New Yorkish.’ The Golem is an Old Home creature, destined in some way to remain behind there. I also think of the uncreated Golem’s pleas not to be ‘born.’

And not unlike Leivick’s explication of ‘Ergetz Vayt,’ with the blizzard that equally could have been Philadelphia or Siberia. Equally, Leivick mentions his own ‘prison-like’ nature in 1937’s Lider fun Gan Eyden — exile and prison both left behind and coming with on further travels.

The subject it touched on in his poem ‘The Lament from All Houses,’ (In No Man’s Land, 1923), where he, as a tradesman, is witness to the private misery behind the doors of the apartments he visits.