Part 13 can be found here, and the series begins here.

‘Don’t Forget The Tears of David’

In the span of the scant week that I spent in hospital in Jerusalem, and then the couple weeks in the Hotel Eden, still as a patient, I had good opportunity to follow almost all the Israeli press in Hebrew and in Yiddish, as well as the magazines. Through them, I could more or less experience the cultural processes which took place in the state of Israel and also the state of mind of the writer in Israel today — both of the Hebrew writer and of the Yiddish writer. In addition, even more helpful colleagues who came to visit me. They displayed much closeness to me and also much willingness to engage with me in conversations which interested me regarding the mental state of the writer in Israel generally, and the Yiddish writer in particular.

Of course, it was clear for me, as it is also clear for me in America, since I live there, that for a writer the problem of literature is not the sole matter which must occupy them twenty-four hours a day. They must know, and know, that in life there are many more matters which must interest them. In Israel, where the people are zealously captivated in building, in integrating, in establishing forms of life, in struggling and fighting with the surrounding enemies and in still more struggle with itself — in such a national atmosphere the writer certainly knows that outside their creativity, in their four cubits, the surrounds, the noise, captivates them no less. They must keep a close watch over themself that they don’t stray too much from their creative four cubits, in order not to be lost in the too-political, too-social rush. Conversely, they must be on guard they do not creep too far into sunkenness, into isolation, which can transform into unhappy uncreative solitude at the time when solitude itself, creatively, is their most wished for personal climate.

In that sense, it was clear for me that there was no different between the Hebrew writer and the Yiddish writer in Israel. In an age of great societal, patriotic and political struggles, when the political is the model for the situation; the poet or the novelist must be moved a bit, and even pushed, into a corner, and the poet and the novelist and even the essayist accept it as a natural thing. It’s only bad when the political wants to displace, wants to make banal writers of them, and if they do not allow it — they scorn them, ignore them, and so forth. This, thank God, doesn’t go on in Israel. Literature for its own sake is surrounded in great respect and honour. So is the writer as an individual.

It became clear to me that the state of Yiddish in Israel had, in the span of recent years, changed much for the better. No comparison to the situation during my visit in 1950. The language war, in a practical sense, had almost entirely disappeared. When I say ‘almost,’ I have in mind the few exceptions to the whole, which I mentioned in previous articles and termed them: ‘Nettles in the blooming cultural garden in Israel.’

The truth is that I don’t understand them, these nettles. By no means. I don’t comprehend their mentality. I don’t grasp their annoyance. If, behind them, there stand however many creative writers — I grasp it even less. How can a creative person, who has whatever connection to the essential meaning of the word, speak with hatred about Yiddish and Yiddish literature, nurturing within themselves the dark dream of the downfall of Yiddish and expressing themselves in hairsplitting about a language to which generations of writers have devoted, and devote today, their lives, their souls, their song and prayer? How is it possible not to understand that a language, to a true writer, is not a meaningless garb which one can put on and take off for one reason or another.

I truly don’t understand these exceptionally extreme opponents of Yiddish, and I was gladdened to feel that they were indeed exceptions to the whole today in Israel. I was happy to see that Yiddish occupies a position it has made for itself in Israel, ‘without shame and without rivalry’ regarding Hebrew, and the position becomes natural, the more the creators becomes intimately woven into the energetic creative processes of the state. The widespread newspapers, Letste Nayes, Di Goldene Keyt, Heymish, Lebns-frages, Folk un Tsion, the new press at the I.L Peretz Library, are good, outstanding signs of this integration. (I don’t grasp the bizarre curiosity of why the newspaper Letste Nayes must change its name half the week. — I do not understand it).

Ignoring this general satisfaction which dominates me, and also ignoring that in the essence of writerly destiny I felt no difference between the Hebrew writer and the Yiddish writer in Israel — I must, however, confess that as for the writerly mood, most of the Yiddish writers in Israel made an impression upon me that they carried within themselves a particular hidden sorrow. I considered this a great deal during my current presence in Israel. I listened to their talk, to their words and between their words; I followed their movements, facial expressions. Watched, moved, and, I may say here openly, with much love. I made comparisons between their literary mood and the mood of other Yiddish writers in America. The analogies didn’t agree, although it could seem that in a few details there was a similarity. This illusion, though, quickly disappears when you see clearly that you can in no manner compare the English climate, in which Yiddish finds itself in America, to the Hebrew climate in Israel. About English, a Yiddish writer in America, if they want to be a Yiddish writer, can say that it isn’t their language nationally, historically, according to destiny, but about Hebrew in Israel, they cannot say it, may not — in themself — say it, and indeed does not say it. They cannot say it, just as they cannot imagine and cannot grasp that a Hebrew writer might also say that Yiddish is a foreign language.

Here there come together two relations who don’t know themselves how close they are. They look in the same mirror and yet sometimes it seems to them that they don’t look good to one another,

The creative person can be at war with everything and everyone, they can be a greater war with themself; they can, though, not be at war with their calling, with the basic essence of their creativity, unless they should annihilate or give up their calling.

In order not to annihilate or give up their calling, they must make peace with it. What’s more, they they need to be in full harmony, in full consciousness of primacy, of self-recognition, this is the commandment of creativity and particularly of the creative word.

And here, in the Yiddish writer in Israel, there occurs the drama of maintaining this creative harmony.

In their words and in their work, I have more than once heard their dramatic dialogue which they lead with themself, I I felt in my senses the creative potential which lies in them and awaits a still greater awakening of their will, of their unrest, of their falling to the great wellsprings of the people’s weeping and song in Israel.

A short time before my departure from Israel, I asked our A. Sutzkever if he would, if it was possible for him and his wife Freda, call together a meeting of Yiddish writers in his home for a friendly conversation. Sutzkever and his wife did so willingly, inviting as many colleagues as the house was able to hold. Even more than it could hold. There gathered around thirty-five, forty people. The meeting was a truly festive one. And even more than that. After an introductory word, where I said that I was intentionally out to stimulate the colleagues into a conversation about their writing lives in Israel, about their mood, about their joys and difficulties, the conversation indeed began, unspooled — from the beginning of the evening until late in the night.

It annoys me to this day that the words of the colleagues weren’t recorded and that I, myself, didn’t note them down on the spot. I thank colleague M. Grossman that he, in his monthly journal Heymish, from October 1957, set down at least a summarised report about the evening, and worked out that after my word of introduction, there spoke, according to the order he gives: A.M. Fuks, Y. Perlov, Y. Hofer, M. Grossman, A. Shamri, A. Karpinovitsh, Y. Spiegel, the painter A. Bogen, Y. Zerubavel, M. Tsanin, Y. Papirnikoff, A. Liss, Y. Oren and A. Sutzkever, who, amongst others, said that this was a writer’s conference in miniature. — If I’m not mistaken, the poet Eichenrand also spoke.

A. Sutzkever’s remark, that it was a writer’s conference in miniature, is, in actuality, a correct one. I send him and his wife, even today, thanks for calling the meeting together. The impression of everyone’s words still lives in me today. Some spoke with sorrow in their voices; some with reproach, both to themselves as well as to those around; some — with scolding and with demand from themselves, with a summons to energy, to great creativity; some with clear certainty and belief in their being in Israel and in their portion which they have in the rise of Israel. One thing shone from everyone: self-reflection, brightness of survived suffering and love for the earth of Israel, which is their Jewish home; — a denial of a dated, false tale that Yiddish and Yiddish writers — Yiddish literature general — is antagonistic to Jewishness, to Jewish tradition, to Eretz Yisroel, etcetera.

Such a mood of self-reflection, although in a different manner, I also experienced at the parting evening with the Hebrew writers in Haifa. It filled me with strength and hope that there started to be established a harmony between both our literatures, which is, at its core, one literature. With this mood of self-reflection and hope, I travelled to Haifa harbour, to the ship ‘Israel,’ which would take me to New York, and in my heart there smouldered hot my desire to quickly return to Israel from New York.

Here, generally, end my impressions of Israel, which I present in a much-shortened form. I feel, though, that I cannot conclude them where I will, in a few lines, at the very end, without relating the unsettling moment which I experienced a day before my departure, visiting with our Dovid Pinski.1

Traveling, in the company of dear Abba Hushi,2 the head of the city of Haifa, to the port, we passed by Dovid Pinski’s house on Carmel. There trembled in me, stronger still, my desire to part with Pinski.

We go in to him. My wife and I. This is, incidentally, our third visit to him. We see: Dovid Pinski sits in his chair. Opposite him, in the same way, sits his wife, Hodel. A loyal nurse watches over them, supervising day and night.

So as not to shame the wonderful figure of Pinski with realistic depiction, I will say that I encountered him sitting, not in a wheelchair, but on a king’s throne. As it says in the Tanakh about King David: And King David grew old in days. — As King David grew old and was in the depths of his days, the faithful nurse cares for him and his Hodel. This fidelity to them is supported by the Va’ad HaPoel and head of the city of Haifa in partnership with the help that comes from the National Worker’s Alliance in New York through the devotion of L. Segal3 and through the personal commitment of our Mendel Elkin.4

Yes — there stands before you a sort of king’s throne, on which sits our elder, the head of our Yiddish literature. When we go to him, it takes a bit of time — of course it probably must take a bit of time — until he recognises us. When he recognises us, he wishes to say something. Instead of speaking, he begins to cry. Which is stronger — words or tears? I embrace him and from his mouth there finally come a few words which shake my wife and I:

‘Don’t forget the tears of David.’ ———

Yes, the words shake me, and also — they fill me with a sort of biblical exaltation: Dovid sits on his chair and begs one thing: Don’t forget the tears of David. ———

We leave his house. It’s the end of day. The sun goes down over Carmel. We go, and Dovid Pinski’s plea follows us. We descend. And there, high on Carmel, he remains sitting and from his lips, the wondrous words do not descend: Don’t forget the tears of David.5

H. Leivick, Tog, 15 February, 1958

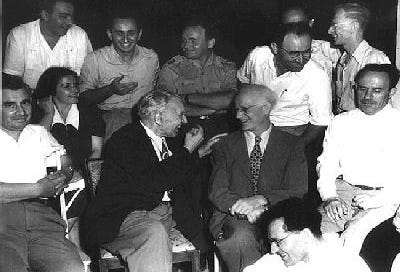

A happier meeting with Pinski in Israel, borrowed from Museum of Family History. I hope they’ll forgive me.

David’s tears — King David’s, to be precise— are mentioned in a few psalms, notably 6 and 56. We started this trip with Tehilim being read on the ship as it comes into port in Israel, and here we return to Tehilim ready to board the ship back to New York. God, we are told in Psalm 56, not only remembers David’s tears, but has kept them all.