Something a bit different — I’m going to try walking through this play act by act, one act per week. It can be difficult to get a real sense of a piece meant to be performed from excerpts or even a full play script.

I’m also going to preface this series with a warning: The language around and treatment of disability in the play are problematic, but must also be taken within the context of time of composition. While everything I write is meant with affection and respect, I do also try to retain a modern and critical eye. I have retained occasional usage of ‘Deaf-Mute’ as the name of one character for discussion, as that is the name he is given in the text itself.

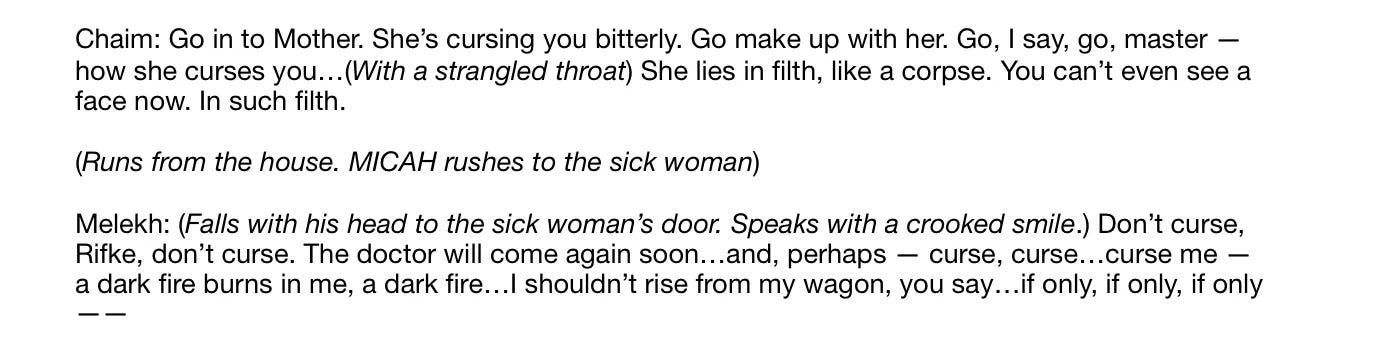

From Forty Years of Folksbeine, 1955. Likely from Act Three, when most of the characters assemble under a bridge. The play was first staged as Beggars by Schwartz’s Art Theatre in 1923. If you look carefully, Melekh appears to be in a uniform, wearing medals, closer centre, slightly left. Hinde holds her bird cage, and Zerekh wears his placard identifying him as blind at far left.

Poor Kingdom’s Melekh tells us exactly what he is in the first act:

A man at war against the world. And which of Leivick’s protagonists isn’t at war with the world or some aspect of the way it operates? Even if it’s only the world within himself.

Marcus, from Leivick’s previous play, Different, lays out a not-too dissimilar battle plan to the police captain who has arrested him, saying that now he has taken off someone else’s uniform he will put on his own. And as for his army? ‘There is no army for my war. I must first awaken my army, exhume them from their graves and resurrect them.’ He burns his tiny, claustrophobic world of the store to the ground, as a metaphor for the actual world that he doesn’t have the power — yet — to torch.

Poor Kingdom’s curtain rises on a hovel somewhere in New York from which Melekh — a beggar from a long line of honest beggars — has ascended to a sort of pseudo-royalty as a dishonest one, faking paralysis and riding around in a wagon.

There’s no subtlety at all in Melekh being king of the beggars. It’s right there in his name. His kingdom? The little cart he uses to propel himself around.

But, of course, he has eyes on a much bigger kingdom than that.

Melekh’s elderly and blind father, Micah, recalls the good old days of tramping the roads from Minsk to Vilna, making a living through the kindness for one’s fellow man. Melekh’s son, Chaim, is disgusted by the money he has hoarded away while pretending to be disabled. His wife, Rifke, lies in a back room, so ill that she’s become a secret, almost faceless horror, lying in filth while Melekh has thousands in his bankbooks.

Melekh’s fire, in contrast to Marcus’s, is in him and will remain contained there. A dark fire, he says, burns within.

From H. Leivick, Poor Kingdom, 1923.

And fire is such an important image and symbol for Leivick that it is well worth noting who and what is marked by it — and what, textually, it is signposting. Here, the fire draws our attention to the dying curses of Melekh’s sick wife, Rifke: May he not rise from his wagon.

While Melekh is not the physically paralysed man he plays at being in public, Leivick quickly sketches out for us what it is he does suffer from: a spiritual paralysis. One of the soul.

There’s a major Levickian theme here, one which recurs over many, many plays: that of fathers and sons and the conflict between them. Here, we have three generations under the one roof. Here, as they so often do in Leivick, they fail to see eye to eye. There is, perhaps, more in common between Chaim and his grandfather than either of the has with Melekh. While Melekh wants money, empire and a younger, prettier wife…the other two yearn for the days of old world, holy begging.

And holy begging is what it is. If we look over to another play of Leivick’s from roughly the same period, The Golem, we again have a decrepit room full of beggars, many of whom are physically disabled.1

Leivick often lists off the more eccentric characters of his home town, amongst them several disabled beggars. In fact, he even says that he wishes to be one in ‘The Towering Life’/‘Here Lives the Jewish People.’ Which is partly tied to his personal conviction that there is the potential for any of them to be one of the hidden Lamed-vovniks, the holy people upon whose existence the world depends.

From Y. Pat, Conversations with Yiddish Writers, 1954.

It’s certainly not, not to modern eyes, any more satisfactory a interaction with disability to treat it as a marking of divinity any more than to treat it as an indicator of personal morality (something, NB, this play deals in heavily). But Leivick does assign otherworldly powers and a certain morality to his truly disabled, physically and mentally, characters. Which Melekh, of course, is not.

Leivick’s blind men see more, his mad men know more, than the ordinary person. His speechless characters, perhaps because of his own silences and desire for silence, are prophets. The blind Zerekh, here in the first act, has what could be termed a vision:

From H. Leivick, Poor Kingdom, 1923.

Amongst the beggars of Golem are also Elijah and the Moshiach. And they, of course, constantly turn up in Leivick’s work, largely concealed amongst the lowest, most anonymous classes of the play. In Golem, they hide amongst the beggars in the Fifth Tower. In Wedding at Foehrenwald, Elijah is amongst the survivors in an overcrowded bunk in Foehrenwald DP camps and the Moshiach in a mass grave at Dachau. The beggars, then, also require more than a cursory look here.

This, of course, is a realist play, having more common, perhaps, with Rags or Shop than the stylised/expressionist Different of 1921. It certainly isn’t fantastical, touching on the realms of the mystic, and religious in the same manner as Golem.

But further connections to Different are easy to find below the surface. While Marcus’s uncle and business partner have ‘increased their stock’ and profited during the misery of the First World War, Melekh’s busy increasing his human stock — his stable of beggars — and his also profiting, though in a more direct way, off the misery of humanity and deception. Its all about growth and monetisation, as he brutally lists off the business acquisitions he want to make to his increasingly dissatisfied with his lot lieutenant, Yonah:

From H. Leivick, Poor Kingdom, 1923.

He’s going to branch out, Melekh says, into blind musicians. Because ‘suckers’ love love songs sung under their windows. He even wants to get a foot in the door of the churches.

To be continued…

I’ve previously spoken a bit about the treatment of disability in Leivick’s work, including that in In the Days of Job.