— For the premiere of the drama Rags — [Leivick] recalls — I came straight from work. Scarcely succeeded in taking off my ‘overalls.’ Didn’t want to be late on account of such foolishness.1

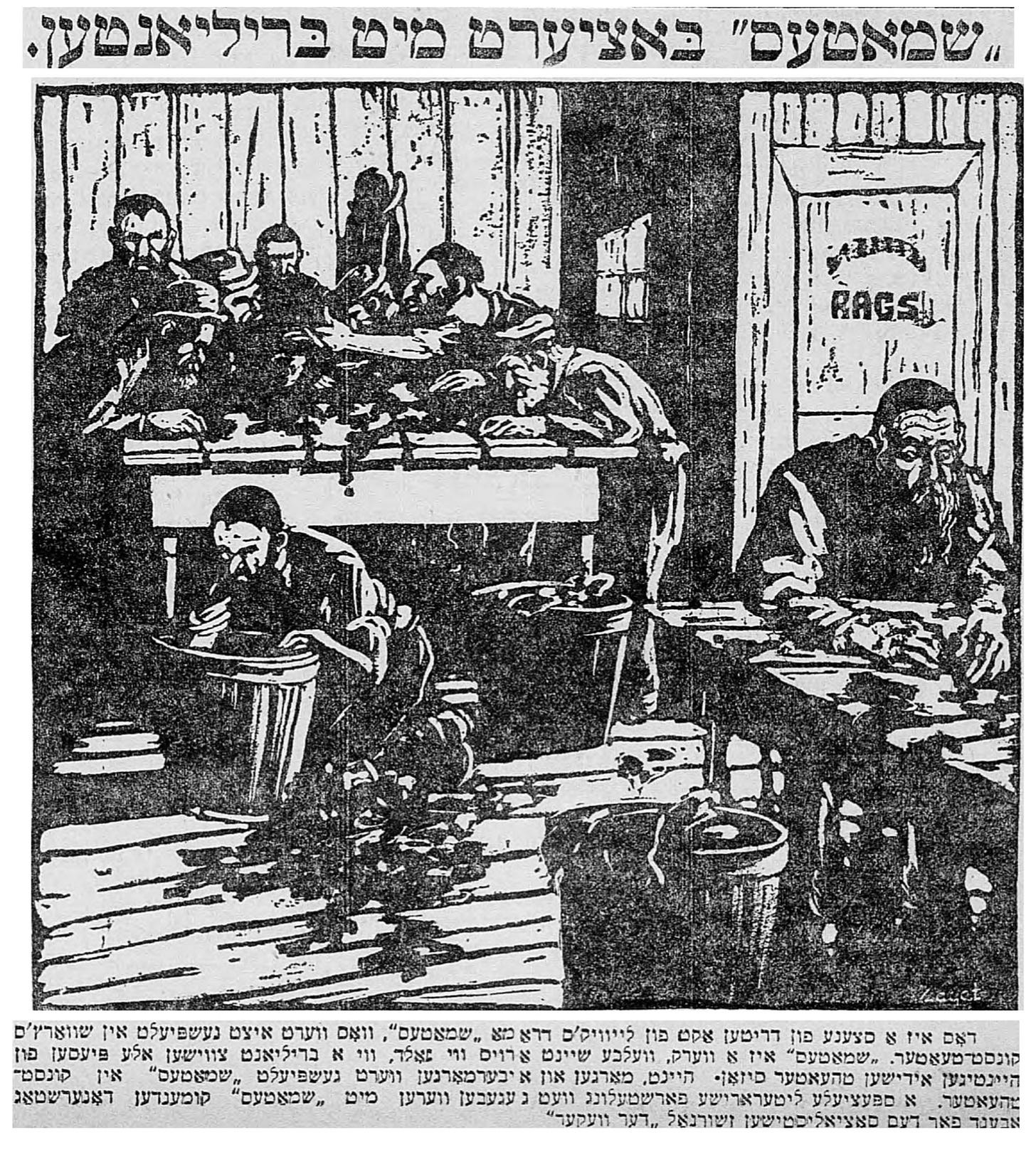

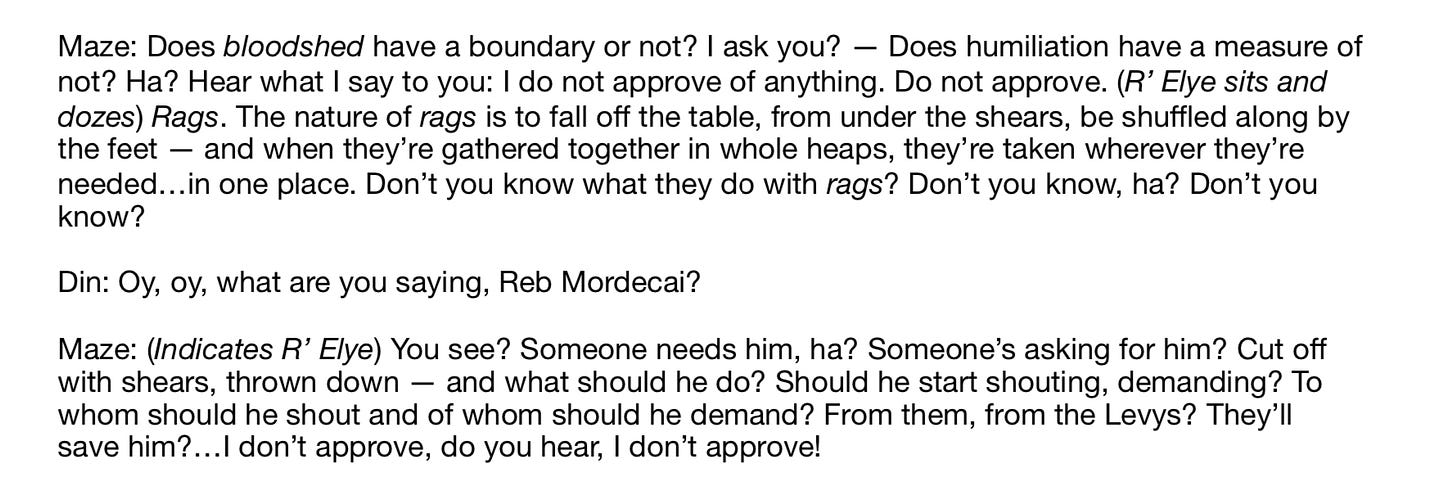

Act Three of Shmates drawn by Samuel Zagat for Forverts, December 23, 1921.

I wasn’t going to write about Shmates (Rags, 1921).

Not because I don’t like it, I very much do!

But I largely prefer to stick to things that really haven’t been much explored — or at all. Not because I feel that I can’t revisit them or that I can’t add anything, but because there’s far too many riches to dwell on the same things over and over again.

This is, incidentally, also the reason for my semi-serious boycott of Golem.2 I like it, even love it, but who needs another essay on it? You can even choose your favourite translation/version — a luxury not afforded by an awful lot of Yiddish plays.

Shmates, revived relatively recently by New Worlds Theater Project (in 2012) as Welcome to America, is fairly easily obtainable in English. As are reviews of that production. And it’s happily been acknowledged as a pretty brilliant piece of theatre, one which displays the other half of Leivick’s oeuvre so well. For every Maharal, there’s a Mordechai Maze.

(More on that later.)

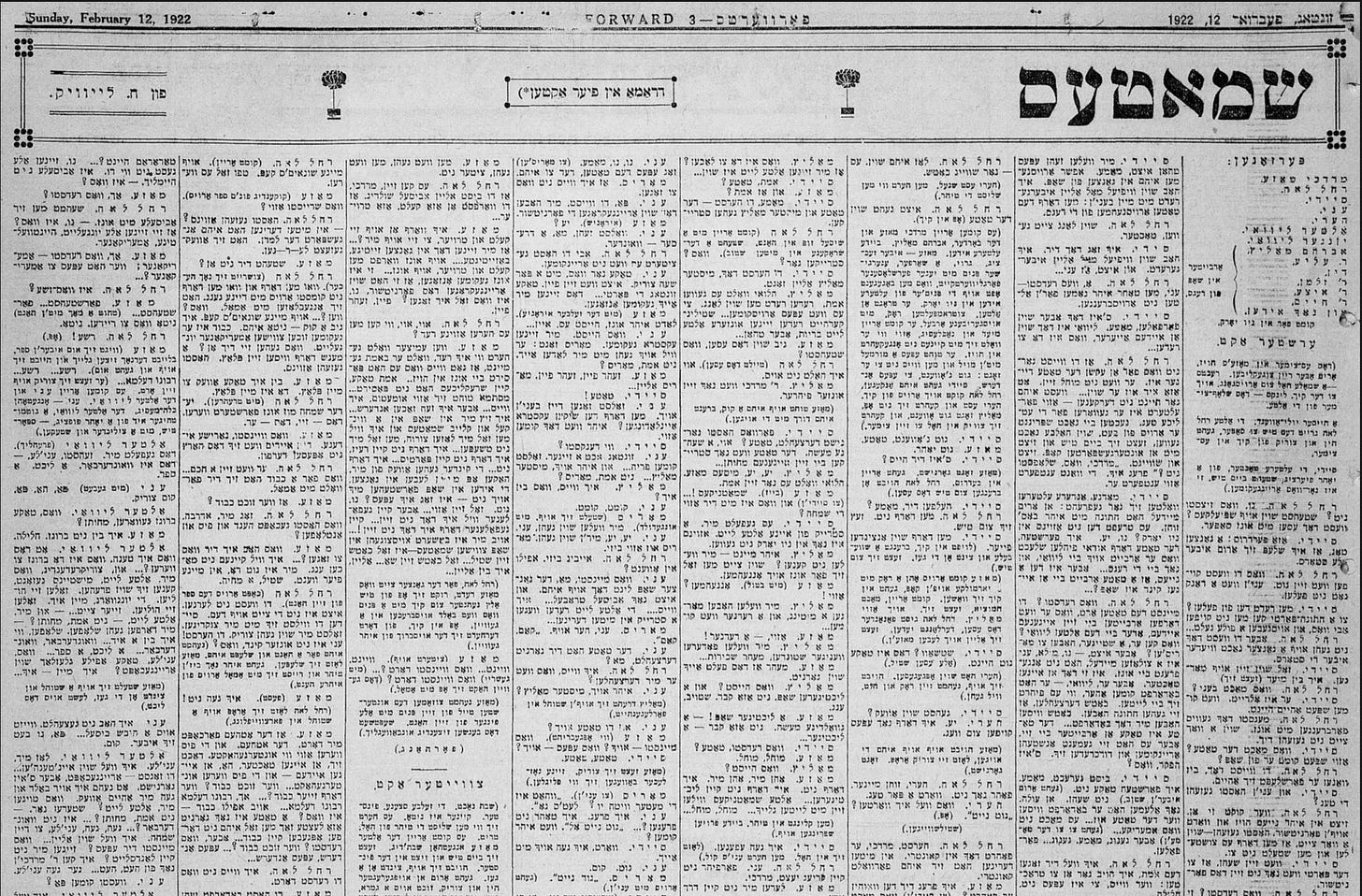

Any way you look at it, Rags is hardly an under-appreciated work, either now or in its own time. In interview with Y. Pat in 1954, Leivick says the play earned him about $5000 dollars — a life-altering sum of money for someone who, a few years earlier, made about 6 dollars a week as a paper-hanger.3 It was even published in its entirety in the Forverts.

But precisely because of this, there’s something which compels me to revisit it now, with Leivick’s other dramas largely behind me. So here I am.

The heart of the play, the peg that absolutely everything hangs on, is Mordecai Maze. And what a character he is to have shown up in Leivick’s ‘first’ play.4 There’s nothing quite like him in any of the others, though some characters are clearly shades and shadows of him, or mostly-futile attempts to capture him again. Shmuel Charney writes of Maze:

To me, though, it appeared and also still appears now, that the true name (thus the core) of the drama is not Rags, but Mordecai Maze — the name of the main character. Not rags, but, on the contrary, a bit of moral granite — that was what hovered before my eyes when I left the theatre. The problem of economic downfall did not interest me, but the drama of spiritual opposition to exterior decline. Not the weakness of a impoverished person, but the strength of an old, embarrassed pride…I saw: hasty arrival of wind-driven, murky waves, they cast themselves on a stone, wearying themselves in swallowing it, washing it away, crumbling it, but it — with silent, noble, blessed persistence — remains standing firm on the spot.

From Charney, H. Leivick: 1888-1948, 1951

According to Charney, Mordecai Maze is largely based on Leivick’s real-life father-in-law, Samuel Sultan.

I don’t have much information about him, but the handful that I’ve got certainly makes sense as to how the real man might well have been translated to the stage; in the 1910 census, Samuel Sultan is listed as working as a pedlar on his own account. But if we look at their marriage record, we see that Leivick and his wife Soreh (née Sultan) were also married by a ‘Rev. S. Sultan.’ The Museum of Family History, in their listing of former synagogues, notes that a Samuel Sultan was sexton (Shammes) at Congregation Kol Israel Anshi Poland, 20-22 Forsyth Street, in New York in 1915-1916.

Note that address of 20-22 Forsyth Street for the ‘Official Station,’ aka: Congregation Kol Israel Anshi Poland. Also, ‘Leon’!

Provided that’s not all a very large and somewhat far-fetched coincidence, it essentially gives us the origins of those two sides of Mordechai Maze: the one trying to make ends meet in one of the archetypal jobs for Jewish immigrants of the period and the one which remains unchanged by the ‘new home,’ bound to his internal, historic, religious life.

At least one critic likens Maze to a forerunner of Arthur Miller’s Willy Loman5 — at war with his family, with America and its dreams and aspirations. Perhaps Mordechai Maze could even be Willy’s father or uncle. But there aren’t so many aspirations and dreams in Maze, not when we meet him (his children are a different tale). He doesn’t want attention to be paid, at least not any longer, if he ever did. What attention is paid is either cruel or belittling. He wants to be left alone, to be silent, to remain himself.

While there may not be dreams of a future, there’s a struggle to keep hold of something fundamental to him, of the past. In this case, it’s his incessant return to study his seforim, his holy books, at night. When the new world is too much, too cruel, too obsessed with status and money and possessions — we see his younger daughter anxiously awaiting her ordered furniture, she’ll just die if it doesn’t come — he leaves her wedding party to return to his own dearest possession — his seforim. Toyrah is di beste schoyrah,6 after all.

And he remains largely silent.

The play which immediately follows Rags is Different — an enormous flop for Leivick and Schwartz’s Art Theatre — and Charney is also quite critical of it, comparing the protagonist, Markus, to Mordechai Maze, seeing them both in revolt against their American environment. Charney says, that despite this similarity, the reason Maze and Markus differ, and why the former succeeds while the latter largely doesn’t, lies principally in the volume of their speech:

The internal ‘difference’ in the post-war Markus is greater, more intense, than in the older Jew, Mordecai (in Rags) — and it is also expressed more powerfully, more dramatically, in this case — more theatrically. Mordecai Maze did not speak. Markus speaks. He speaks too much. It was as though Leivick feared the audience and the audiences’ representatives in the press had not instantly understood Maze’s speech, Maze’s silence. He made the hero of his new drama too talkative.

Charney, H. Leivick: 1888-1948, 1951

Apart from that brief foray into the rag shop, everything happens around Maze’s table, where he sits and studies and glowers.7 Where he will eventually break his silence and declare his son to be his deadly enemy — the conflict between fathers and sons, those immigrated and those born in America, one of those themes which Leivick revisits over and over. The play begins with a very quick overview of precisely this situation, the war which has begun between father and son. The son attacks, we are told by Maze’s wife — though never truly shown — and the father takes it.

That’s America, his eldest daughter says.

We aren’t told where each of the children was born, but of the three, the eldest, Sadie, is the most old-world in her values. Even she, though, dreams of ‘her Benny’ becoming a boss — a thing we’ll see in Leivick’s later play, Shop. The dream isn’t to have the time and security to study, but essentially to become the oppressor, the landlord, the shop boss and think you’ll do it better, make more money at it…

Regarding the Maze’s two younger children, and particularly his son, Harry, however:

From H. Leivick, Shmates, 1928

We’re essentially encouraged to imagine this scene, and the son who runs straight back out to play ball, the one who speaks mostly English (‘boy’ in fact, when Sadie’s talking about Harry, is in phonetic English) the one who’s using his vacation to go travelling cross-county, even missing his sister’s wedding, in all the houses. Each of Maze’s married coworkers presumably goes home to the exact same scene, the exact same poverty and the exact same ungrateful, disrespectful child(ren). More than disrespectful— actively ashamed of their parents. Fleeing them.

The entire difference lies in Maze. His coworkers, when they come to his house, find him studying. A thing they ceased to do a long time ago, either drifting, surrendering or forgetting this aspect of what they once were.

There’s actually a second character who’s a version someone that Leivick actually knew, and that’s Maze’s coworker in rag-picking, Reb Elye. Charney tells us that he’s based on Leivick uncle, also a Reb Elye, who was apparently employed in a rag shop: ‘a ‘broken vessel,’ a rag on two weak legs.’8

And this is where Charney starts to get at the stated theme of the play, the human ‘rags’ picking through the material cast-offs of their new world. The repetition of ‘rags’ works here. The repetition of ‘different’ doesn’t — you can’t pull the same trick twice and expect the same applause.

The name is: Rags and in the piece itself, in every act, there repeats without end the word: rags; in the third act there is seen an entire shop full of rags and people who are rags. It seems that the author truly desires the image, the symbol of the ‘rags.’ Without stop and without hope it buzzes in the ears: rags, rags, rags…

Charney, H. Leivick: 1888-1948, 1951

Reb Elye, in particular, mourns his loss, feels guilt over it, but can’t adequately explain, for all his words, why it’s happened. He has the books. He has glasses. But he lacks the culture around him which valued this study. The Hebrew letters are both his own — and no longer his.

And his verbose weakness of will is all the more obvious compared to the silent, iron one of Maze.

From H. Leivick, Shmates, 1928

The old men of the shop were once something else, just as their rags were once something else. Maze, though, is a different proposition. He rejects everything, both loss and gain. Which is part of why they need Maze to join their strike action against the shop bosses, the Levys, so badly.

From H. Leivick, Shmates, 1928

His iron will is something they lack. He isn’t quite a rag yet, even if the coat he wears to work might as well be. He still changes into his Shabbos clothes to study. That side of him is untouchable, inviolate.

To be continued…

As close as I’ve yet gotten to Leivick himself confirming the story repeated by Ruth Wisse in A Little Love in Big Manhattan of Leivick checking his paste bucket and brush with his coat for the premiere of Golem. From his interview with Y. Pat in Conversations with Yiddish Writers.

I think I’ve maybe talked individually about every play now except for Golem. For what it’s worth, don’t dislike Golem at all. It’s weird, it’s mystical, Jesus appears in it as a character — and is pretty quickly rejected — it’s got all the components which should make it highly attractive to me. But what wonderful things are almost entirely obscured by the Golem’s shadow!

Room and board, for comparison, was three and a half dollars a week by his own reckoning.

I’ve got ‘first’ in quotes here, because there’s technically Chains of the Moshiach, There, Where Freedom, The Golem and an unnamed, now-lost, Hebrew play on the theme of pogroms, whose initial compositions all pre-date Rags. Golem won’t be performed for a few years yet.

Notably, there is an article/review in Tablet, which also gives a good, if ‘potted’ Leivick biography. I will maintain my policy of not linking to them. But I will say, regarding the article, that it’s indicative of the general treatment of Leivick and his work, where appreciation seems to come in waves: someone says he’s brilliant, largely untranslated, why isn’t there more of his work available…and then it all gets shelved for another decade. Clifford Odets is another comparison which arises in relation to Leivick’s realist dramas.

‘Torah is the best commodity.’

The New Worlds Theatre Project version, translated and adapted by Ellen Perecman, never takes us into the rag shop. Which both focuses the play on the assault on Maze’s internal world and, at least in my opinion, slightly misses the mark. I think we do need to see — and also hear — what happens there. Which is the walkout that Maze gets dragged into. But it does focus things — and eliminates the need for another set and a large group of actors only on stage during that scene. You can find Perecman’s version of Rags in Ten Yiddish Plays in Translation, (2020).

‘Broken vessels’ is being used in a double-edged way here…the phrase itself appears in Elyse’s lines, where he’s trying to remember (and mostly forgetting) about Shevirat ha-Kelim — in Lurianic Kabbalah, if I maybe forgiven my layman’s understanding of it, the breaking of the vessels during Creation. And also referenced in Leivick’s idea of poetic creation, which even makes its way to appearing in Harold Bloom’s book on Kabbalah: a poem means ‘filling the pitcher’ until it overflows, until you break it. The creation/destruction duality is a bit concept for Leivick, each predicated on the other.