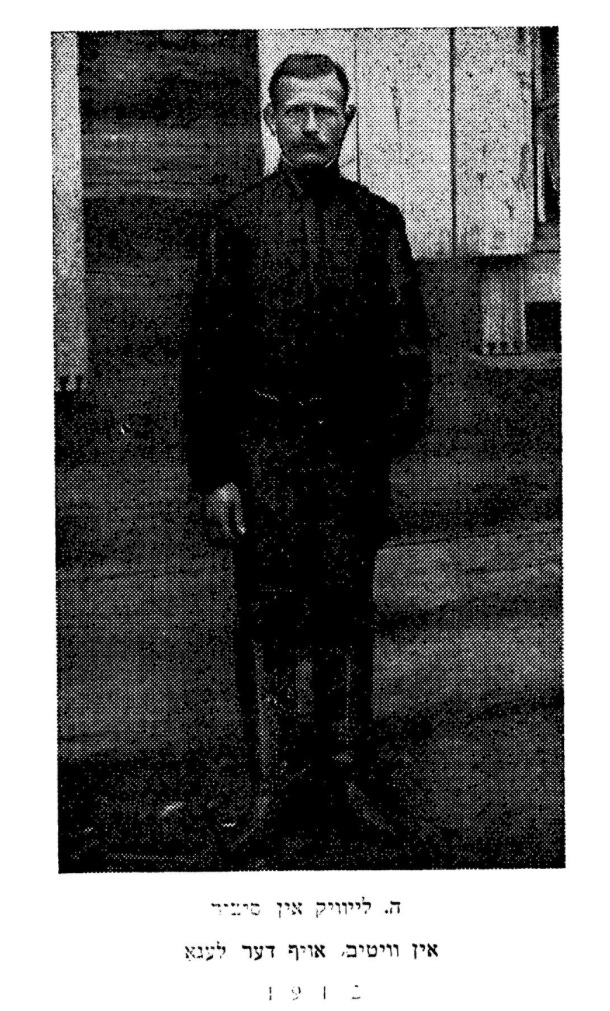

If Koytman and Levine are two opposing aspects of a single person —

the part which does not wish to shed the prison coat (Koytman) and part which cannot give it away quickly enough (Levine) — as explored the the first part — then the female leads of There, Where Freedom can be seen as representing conflicting destinies.

Lena, of course, is Siberia; Full of wild beauty, life and light, entirely free of societal convention. A manic pixie peasant girl, if you will.

She first clings to Koytman, trying to entice him from his self-imposed exile within his official one. And then greets Levine when his own wife is a few moments late meeting him when he arrives on the prisoner ship. By pouncing on him.

Instead of home and his familiar life, he is welcomed by this wild, entirely new experience. He’s frighted — but the fright is only momentary. The portrait Levine eventually paints of her is full of life and light. She is, in fact, life. We’re not subtle here.

From H. Leivick, There, Where Free, 1912/1952

But as the play goes on, we start see the other side of her, as well. Neither man has yet weathered a winter with Lena, though Koytman gets a taste of it (admittedly in response to his own turning out the lights and declaring she not longer exists) and her utter chill when Lena she switches her affections to the new arrival. She is, we see — and both Koytman and Rokhl see — dangerous to them.

Actual winter is also encroaching at the end of the play, and we are left to wonder what will become of all of them, particularly when the snow starts to fall and the days grow shorter and colder. You should see the sunrises then, Lena says.

If Lena is free, liberated, and wildly inconstant with her affection, Rokhl Levine has been doing time just as surely her husband Dovid, even if not behind bars. She has, catastrophically, in Levine’s eyes, changed over the past seven years from the woman he fell in love with.

From H. Leivick, There, Where Free, 1912/1952

Rokhl’s single-minded devotion leads her to place herself entirely at Dovid’s mercy. She refuses to make a fuss about her sacrifice in going to Siberia so Dovid doesn’t feel guilt — imprisoned again. She’s actually a far better revolutionary (according to Leivick’s notions) than either he or Koytman is, offering to leave Dovid, subverting her own life and desires, in order to give him ‘full freedom.’

From H. Leivick, There, Where Free, 1912/1952

She starts to prepare for their escape when he suggests it. In the end it seems that she will even willingly throw herself into the river — sacrificing herself, in a sense, to the Lena — and give him even this freedom that she sees him grasping at.

And in this means of escape, she’s like Koytman, the other perpetual prisoner. He has also been found looking at the river as though he will throw himself in rather than face ‘surrender’ to another person again by loving them. And attempts to shoot himself in the final act.

No one, in fact, aside from Lena, is truly free.

Not even Chaim Vakhlin, the former criminal prisoner who makes much of his freedom and the beauty of Siberia, is truly free. There’s an undercurrent of sorrow and loss in him, as well, for the family he never allowed to join him and whom he never rejoined. It’s made clear in his figure that Siberia is not just a place of liberation, but also a place where one can be irretrievably lost and rely on telling oneself comforting stories about happiness and impossibilities to soothe the ache. Yet another aspect of a fragmented Leivick, perhaps, a version which doesn’t escape?

The drama, the relationship between the main quartet, is almost all revealed in the portraits which Dovid Levine has produced of the other three.1

Koytman’s portrait, we are told, doesn’t bear much physical resemblance to him, but is proclaimed by Koytman himself to reveal something in his soul. Rokhl’s portrait, in which she hardly recognises herself in the sorrow of the eyes, is recognised by others readily as being her. They are, as both Rokhl and Vakhlin say, chilling. There is something deeply unsettling, unnerving about them and what they say about their subjects. We, as the reader/audience, only have them described through the words of the characters.

And then there’s Lena’s portrait — which we do see — and the intimacy it represents.

Both Rokhl and Koytman are shocked by the rapidity with which Levine sets about painting Lena. The process itself, the mere suggestion of it, is treated by the two of them as the beginning of an affair, before Levine even helps himself in taking down Lena’s hair and arranging it over her shoulders. Rokhl acknowledges that she can’t easily see the line between Dovid her husband and Dovid the artist — she says she knows they’re two separate people. But are they really? Dovid himself doesn’t really seem to believe this.

There, where free — but what is freedom? And where is the ‘there’? Is it actually in Siberia or is it somewhere else? How long, Koytman — and thus Leivick — asks can we be free before being enslaved by something else?

From H. Leivick, There, Where Free, 1912/1952

Koytman, Levine and Rokhl all tell us, in one way or another, that freedom lies in death.

But Lena, whose portrait shines briefly before Koytman rather symbolically punches a hole in it, tells us that it is in living.

While Leivick recycled Levine’s name for one of the protagonists of Chains, the love triangle between Lena, Koytman and Levine seems to be the ancestor of the relationships, in revisited, altered, American form, in 1924’s Bankrupt.

And I can’t help myself, I have to leave you with one last, rather beautiful and terrible image which echoes Leivick’s own writing about Siberia and escape.

I’m still wondering when, exactly, Leivick read Wilde’s Picture of Dorian Gray (because he did).